The coronavirus pandemic has seen religious leaders call for peaceful coexistence to triumph over division, and interfaith responses to aid the vulnerable have offered an encouraging sign of this possible future. Yet old divisions run deep. James Walters sees in the resurgent nation-state and increased social instability the potential for further religion-infused populism and the scapegoating of minorities. Political and religious leaders alike have a responsibility to promote lasting community cohesion.

Prominent religious voices are calling for the coronavirus pandemic to be a time when humanity comes together across religious differences. The Estonian Orthodox composer Arvo Pärt told a Spanish newspaper the virus is showing us ‘that humanity is a single organism and human existence is possible only in relation to other living beings.’ Pope Francis’s Urbi et Orbi address on Easter Sunday argued that ‘This is not a time for division.’ Among other conflicts he highlighted the religious tensions of the Middle East, suggesting that the shared threat of COVID—19 was an opportunity for Israelis and Palestinians to ‘resume dialogue in order to find a stable and lasting solution that will allow both to live in peace.’

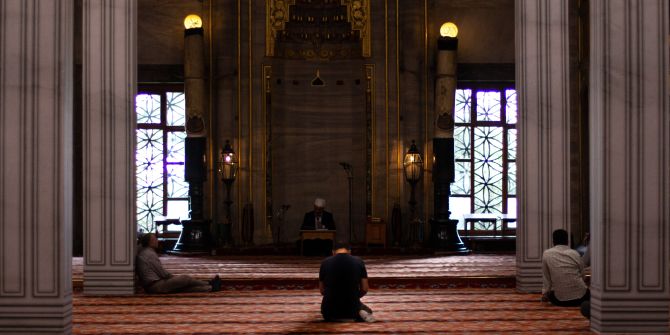

In various settings, addressing the pandemic is providing a common purpose in the face of religious tensions. Religions for Peace has launched a Multi-religious Faith-in-Action COVID—19 Campaign to involve religious leaders in global responses to the crisis. An image of Jewish and Muslim paramedics praying together in Jerusalem has gone viral. Here in the UK, well established interfaith networks are responding to local challenges such as a collaboration between interfaith volunteers in Bradford to support elderly and vulnerable people. We may hope that such initiatives are a reversal of the trend towards sectarianism and religion-related conflict that we have seen across religious communities in the first two decades of the twenty-first century. But there is much cause to fear that the aftermath of the pandemic will see an exacerbation of these tensions. This is for three reasons.

First, the rise in intolerant religious expression in recent years has frequently been fuelled by a closer association of nation-states with their dominant religious identity. Populist leaders have evoked religion as part of their nationalist rhetoric, often claiming to be its champion in the face of real or perceived persecution. Whatever else results from the COVID—19 pandemic, the strengthening of the nation-state looks certain as governments enact far-reaching powers to protect their citizens, with generally strong public support. As social anxiety and economic insecurity persist, heavy-handed leadership with strong religio-cultural messaging is likely to fan the flames of existing interreligious tensions within states and across borders.

Second, this crisis has intensified what is perhaps the primary driver of contemporary religious resurgence: a pushback by many religious communities against a sense of secular encroachment. The story of modernity is not so much one of the reduction of religious belief as it is the reduction of the domain of its expression. Areas of life that previously required theological explanation or a spiritual response are now understood within the “immanent frame”. We live in what the German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer described as “a world come of age” where religion’s natural place is thought to be contained within personal sentiment and private gatherings. Religious resurgence in our age pushes back against this containment in various forms, whether in the growth of faith schools or a rejection of a moral order based on secular human rights.

COVID—19 is the first global pandemic of the (post?)secular age. Few governments will give much credence to religious explanations or responses to the sickness. Public health measures can be viewed as representing a major incursion of the secular into the religious domain, even to the point of the closure of places of worship. Virtually all major religions have seen incidents of refusal to close places of worship, from gurdwaras to synagogues. Several US states have seen legal challenges to bans on public worship on the grounds of religious liberty. Social media footage of religious leaders defying the ban or offering spiritual cures fuels suspicion of a secular state that many believe had wanted to shut them down all along. And even mainstream religious responses are asking whether pandemic hysteria is fuelled by an atheistic fear of death. “Let us self-quarantine from the panicky and sensational media… and consider what God might mean by this,” urges Sheikh Abdul Hakim Murad. All of this suggests that COVID—19 will foment religious resurgence in both positive and negative forms, not quell it.

Third, we must be aware that the inevitable scapegoating in such a crisis will take religious forms. The Black Death of the fourteenth century saw an unprecedented outbreak of antisemitism in Europe as Jews were irrationally accused of poisoning wells and spreading the disease. Pogroms and bloody massacres followed across the continent as people sought to find someone to blame for the plague that killed nearly half the European population. We may have a better understanding of the scientific causes of viruses today, but the impulse to scapegoat in such a crisis remains strong. Obviously the main focus of blame has been on China and Chinese diaspora communities, but we are already seeing accusatory fingers pointed towards minority religious groups. The UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief has already warned of a rise in antisemitic hate speech, conspiracy theories blaming Muslims for the coronavirus are rife in India and, as Ramadan begins, commentators in Western countries are insinuating that Muslims will be unable to abide by social distancing and so will contribute to the spread of the disease.

What can we do in the face of growing religious tensions? The scale of the challenges are enormous and mitigating them is not simple. Effective interventions to promote freedom of religion before COVID—19 were far from clear and the solutions are no more obvious now. But faith leaders at all levels should be aware of the dangers and further the calls for unity in the face of the threat. Political leaders should be aware of how global dynamics can impact local communities and speak up for oppressed religious minorities rather than collude with popular prejudices. And believers from all faiths should look within their own traditions for the resources of compassion that will reach across divisions in this time of shared fear and loss.

Note: This piece gives the views of the author(s), and not the position of the LSE Religion and Global Society blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

1 Comments