The creation of an establishment religion can inherently alienate religious minorities – turning them into a legal and cultural form of “other”. In this post based on their recent journal article, and published in collaboration with the Political Studies Association, Professor Tariq Modood and Dr Simon Thompson write about the relationship between religious minorities and establishment. By using the UK’s established religion as an example, the authors explore how we can determine if a minority group is, in fact, alienated.

Most people recognise that how a state is related to organised religions and religious communities within its territories can alienate some or all of those communities. What is the process of alienation and why does it matter? To be specific, what normative significance should we give it?

Political theorists have tended to discuss such alienation by reference to a paradigmatic case: namely, when a state uniquely privileges one religion or denomination to the extent of making it a state religion, what in Britain we know as ‘establishment’. Whilst the recognition that this can lead citizens of other faiths, especially in the context of contemporary diversity, to feel alienated is common place, political theorists are divided by what significance this has.

Some political theorists argue that feelings of alienation are too subjective a foundation for an argument for institutional evaluation and reform. This is the view of Cecile Laborde and Sune Laegaard, who understand alienation as merely idiosyncratic feelings. They grant that such a feeling can be ‘crucial epistemic indicators that something has gone amiss’, but cannot amount to a critique of the political institutions, such as establishment, that a group is alienated from. They defend the argument that in any given society establishment can undermine equal citizenship, but they believe that the argument is independent of whether any group is alienated or not. For example, a group may be alienated but has no grounds for being so. Alternatively, a minority may fail to be alienated but establishment may still be the cause of their unequal civic standing.

Laborde’s and Laegaard’s alternative argument focuses on the ‘communicative meaning’ of symbols of religious establishment. For example, the state’s use of a crucifix can imply that Christians are full citizens whilst ‘non-Christians do not belong’. This, they argue, would be the case whether anyone felt alienated by the state’s use of the crucifix or not. Such a use of one faith’s symbol is objectively the creation of a two-tiered citizenship whether the minority reacts accordingly or not. On such matters, then, political theorists and constitutional experts should be able to come to a decisive pronouncement without consulting any minorities.

We challenge this argument by defending an account of alienation according to which it is not merely subjective and reducible to feelings. It is a reason for action in its own right and not merely as an indicator that something may be wrong. Moreover, a lot hangs on how one determines if a religious minority is alienated by establishment.

Let us take each of these points in turn. Group identities, including religious, are socially constructed in a context of collective self-understanding and how others perceive and treat the group in question. A dominant group can have stereotypical views and exclusionary views of a minority and treat them as inferior and subordinate, as an ‘other’. This is likely to mean that they will not properly understand the minority or even care if they do or do not appreciate it in terms of its own self-understanding. They will, in Charles Taylor’s famous vocabulary, fail to ‘recognise’ the group and may actively misrecognise it. This is often the case with identities in a context of unequal power relations and can alienate the minority.

Alienation, then, is a product of inequality and has a cognitive dimension – misrecognition or ‘othering’ – the perception of this othering by the marginalised minority. A minority is able to make such a cognitive judgement because, as explained, it has its own sense of self, which provides it with a basis for identifying the processes and effects of othering and misrecognition. Othering may indeed be connected to various institutions (amongst other things, such as popular discourses and labour markets) such as establishment, and therefore establishment can contribute to alienation and aggravate other social forms of inequality. Laborde and Laegaard recognise that. Our point is that perception and engagement with such othering is a basis for alienation and is not merely a feeling.

Moreover, the normative significance of alienation lies in that citizens should not be alienated from their polity. Like Laborde and Laegaard we appeal to a conception of equal citizenship. While they argue that all members of a political community should enjoy ‘equal civic status’, we hold that the state has a duty of symbolic recognition. Negatively, this means that it must not ‘other’ or alienate its citizens. Positively, the state must make efforts to ensure that all of those citizens are able to feel a sense of belonging to each other and therefore to their polity. Establishment or any other state-religion arrangements, including secularist exclusion of religions from the shared civic spaces, is wrong to the extent it prevents religious groups from identifying with their polity.

This leads to the question of how to determine whether a minority is alienated by establishment, such as the position of the Anglican Church? This question is of little interest to Laborde and Laegaard because they think it is incidental to the normative evaluation of establishment. To us this question is fundamental to what we will call multiculturalist equality. Minorities know best if, to what extent, and by what they are alienated. To have any other view of alienation, i.e., to claim to know better than the minorities in question if they are alienated or not, is to not treat the minorities as equals. The alternative is to talk to the minorities, to engage in multicultural dialogue.

Some reasons for arguing that a particular case of majority establishment causes minority alienation may be empirical, derived from descriptions of processes of othering, the effects of these processes on particular groups, and so on. Reasons of this kind can support the hypothesis that a group is alienated but cannot by themselves prove it. For us, one reason which must be provided as part of the claim that a group is alienated is derived from an account of that group’s collective subjectivity, where such an account is built up from targeted research, organisational statements and debates, publications by faith leaders and public intellectuals, discussions in inter-faith fora, political lobbying, protest and mobilisation etc. Our most important point is that no claim that a group is alienated and has had its civic status damaged is complete without that group’s own account of its situation, and that account must result from a dialogue with that group, and not simply by a purportedly ‘objective’ analysis of the message that establishment is sending.

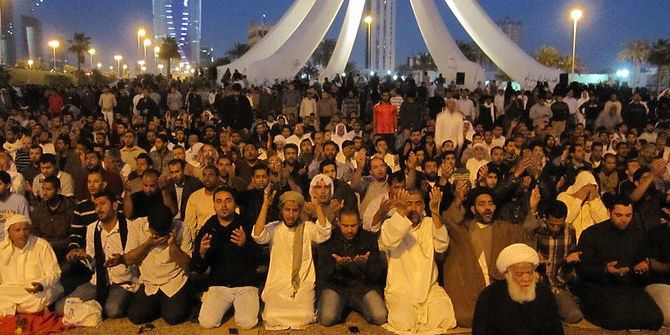

We conclude by making two points. Firstly, it is not our contention that religious minorities in Britain are alienated by establishment. In fact, the evidence suggests that they are not, or at least the case usually cited, Muslims, are not. Our argument is that if they are alienated, then this is a reason for disestablishment or politically engaging with that alienation; and we cannot find out if any minority is alienated without engaging in a multicultural dialogue with it (and others). Secondly, the scope of our argument is by no means confined to establishment. Appropriately adjusted for context, it applies equally to, say, the state-religion corporate partnerships as found in Germany, which continue to exclude Muslims, or to French laicite, which too has been institutionalising the exclusion of Muslims. It may even emerge from multiculturalist dialogue that many Muslims find establishment more congenial than some of the alternatives.

Note: This piece gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Religion and Global Society blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

Note: This article is based on a recent journal article and was published in collaboration with the Political Studies Association.