Does access to riches enable the Gulf states to “buy off” internal religious opposition? While rentier state theory suggests that such governments can normally channel their oil rents to sideline actors pushing for political reform, Courtney Freer argues that this is much more difficult in the religious sphere. Islamist movements mainly provide ideological ‘goods’ to their followers, something governments are limited in their capacity to regulate. As such religious actors can retain a considerable degree of independence from the state.

When it comes to the study of religion in oil-wealthy states of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), the question arises about whether state access to funds enables these governments to exert greater control over religion. Previous work, particularly the strand of literature on rentier state theory, has posited that access to oil rents enables governments to “buy off” political challenges and therefore resist reform toward democracy, rather simplistically summarising political life as “no taxation, no representation.” This literature has thus documented ways in which rentier governments manage to co-opt economically and politically powerful segments of society, yet less attention has been paid to their ability to do so in the social sphere, and particularly when it comes to religious actors. Is the co-optation of religion possible, even in states that can afford to fund specific religious strands?

Before focussing on the Gulf specifically, it is worth noting that, as has been documented in detail by other scholars, Islam has mobilised a variety of political actors throughout the Middle East, meaning that religion is part of political discourse. Debates about the state’s appropriate role in religious life, about the enforcement of religious social policies, and about the place of religion in educational, judicial, and political life continue throughout the Middle East. Further, state concern about the role of Islamist political groups in particular is a major issue in the Gulf.

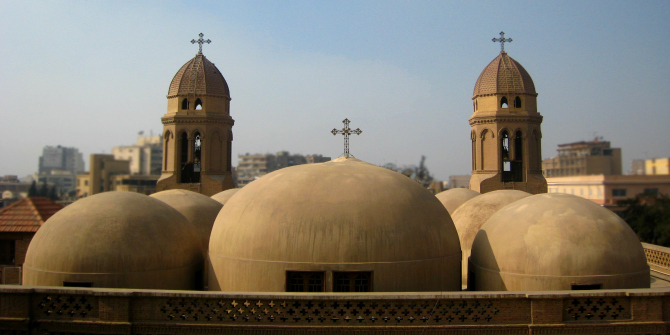

As a result, it is difficult to separate government control over the religious sphere from the control it exerts over political life more broadly. Indeed, in the Gulf, as elsewhere in the Middle East, religion has increasingly become bureaucratised through the creation of ministries of religious affairs and awqaf (endowments). Where the Gulf differs from the rest of the Middle East, then, is not in the fact that state management of religion exists, but rather the extent to which it can be and is funded. Indeed, Saudi Arabia, where the religious establishment is integrated into the state bureaucracy, has famously funded Salafi schools around the world; Qatar has housed the International Union of Muslim Scholars and provides a platform for IslamWeb and IslamOnline; and the UAE has built the lavish Shaykh Zayed mosque, named after the former Abu Dhabi leader and first president of the independent UAE.

Despite their ability, at least in theory, to buy off opposition in the cultural and religious spheres, the Gulf states appear no more effective than non-rentier governments in controlling religious discourse. Indeed, a variety of independent Islamist movements continue to exist within these states. Because independent Islamist groups like the Muslim Brotherhood are not required to provide tangible goods for their followers (though they often do supplement welfare packages provided by the state), they tend to gather followers through their provision of ideological inspiration and therefore are more difficult for states to regulate. The presence of well-funded state religious authorities is therefore not sufficient to stem the tide of independent religious discourse or mobilisation.

Further, while rentier state theory has presumed that political opposition is unlikely to arise in states that provide handsome welfare packages, it does allow for the presence of cultural or religious movements. Indeed, because scholars of rentier state theory have opined that economic levers for opposition will not exist in rentier states, the cultural or religious spheres are seen as a likely source of inspiration for opposition movements.

As a result, the extent to which rentier governments control their religious sectors appears to reflect their political openness more broadly, meaning that independent religious actors behave differently depending on the shape of political institutions surrounding them. Kuwait, for instance, houses a vocal and active parliament, and so Islamist agendas there have tended, particularly in recent years, to prioritise responding to the concerns of constituents and expanding their voter base, rather than providing ideological guidance. In Qatar and the UAE, which lack elected legislatures, independent religious actors tend to focus on issues related to social policy, in particular the sale of alcohol, as well as concerns about a dress code and the importation of Western materials. In Bahrain, on the other hand, where the Shii majority is ruled by a Sunni monarchy, independent Sunni groups like the Muslim Brotherhood are not considered politically threatening and therefore are allowed to contest parliamentary elections, while in other states lacking the same sectarian dynamics, the Brotherhood has been outlawed as a terrorist organisation.

We conclude that ideology, particularly when it comes to religion, is difficult to buy off and therefore can still mobilise political actors even in rentier states. The persistence of independent religious movements, despite the apparent ability of Gulf governments to buy them off, demonstrates the durability of these movements even when we may not expect them to survive. Further, when it comes to the rentier states of the GCC, the same ideological trends that hold appeal in the broader Middle East attract followers there as well; Gulf exceptionalism is not in evidence, although the ability of Gulf rentiers to co-opt certain segments of the religious sector through financing is one important way the Gulf differs from its neighbours.

Note: This piece gives the views of the author(s), and not the position of the LSE Religion and Global Society blog, nor of the London School of Economics.