On 15 June, RGS, together with the US Centre and Department of International Relations, is hosting a free LSE Public Lecture titled Religious Freedom under the Biden Administration. Ahead of that event, RGS and the US Centre’s USAPP Blog have launched a new joint series focusing on religion in American society, bringing in experts to explore the relationship different faith groups have with American society.

Dr Judd Birdsall, a panellist for the event, writes the inaugural post for the series. In it, he outlines how religion and politics have evolved over the past two decades in the United States. Highlighting a series of moments, Birdsall discusses the moments Islam, Mormonism, secularism, Evangelicalism, and – now – Catholicism have had in American politics.

What a difference a decade makes. Ten years ago Baptist pastor and future Trump promoter Robert Jeffress disparaged Mitt Romney’s Mormonism as a ‘cult‘ and denounced Islam as a ‘violent religion‘. Fast forward to 2021 and the lavish loyalty of many of Jeffress’ fellow evangelicals to the now former President Trump has been described as ‘cult-like’ and Christian rhetoric and symbols fueled the insurrectionist violence at the US Capitol.

During the Trump era, white conservative Protestants experienced something of a ‘moment’—a period of heighted attention and scrutiny from journalists, scholars, and the general public. Looking back over the past decade, this evangelical moment was preceded by a post-9/11 Muslim moment, a Mormon moment surrounding Romney’s 2012 presidential bid, and a ‘nones’ moment in the early to mid 2010s. And now we’re seeing what may be a Catholic moment with the election of Joe Biden, America’s second Catholic president.

We can think of the past decade of American religious politics as a series of moments. These moments are somewhat sequential but of course also overlapping, ongoing, and interconnected.

9/11 and the Muslim moment

We begin with the Muslim moment already in progress. Following the 9/11 attacks the United States spent billions of dollars on diplomatic outreach to global Muslim communities—and trillions on wars that undermined that outreach. Domestically, despite the best efforts of President George W. Bush to engage Muslims and praise Islam as a “religion of peace”—coupled with countless elite and grassroots Abrahamic and interfaith initiatives—a virulent Islamophobia began to take root across the country.

Obama came to office in 2009 promising to restore America’s relationship with the Muslim world and to call out negative stereotypes of Islam. His messages (e.g. ‘We are not at war with Islam’) were often strikingly similar to Bush’s. But Barack Hussein Obama brought greater personal authenticity—given his name, Kenyan heritage, childhood experience of living in Indonesia, and his opposition to the Iraq War.

Those very elements of credibility among Muslims made Obama suspect among many non-Muslims. Fueled additionally by conservative media, by 2015, a survey found that 54 percent of Republicans believed that Obama was ‘deep down’ a Muslim himself. To his credit, Romney avoided tapping into this ‘secret Muslim’ conspiracy and anti-Muslim sentiment during his 2012 presidential campaign against Obama—perhaps in part because he could empathize with the experience of misunderstood minority religious groups.

Mitt Romney and the Mormon moment

Romney’s candidacy initiated the Mormon moment in American life. The prospect of a Mormon president brought intense interest in the origins, teachings, and practices of the Utah-based Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The church responded with an ‘I’m a Mormon‘ media campaign, featuring a diverse range of ordinary folks, to help demystify and destigmatize their community. ‘I’m a Mormon’ adverts even appeared on British buses in 2013 around the time that The Book of Mormon musical opened in London.

The ‘I’m a Mormon’ videos, many of which have over a million views on YouTube, don’t go into great detail about distinctive LDS beliefs. Neither do most politicians who are members of the church. Outside of Utah, Mormonism is a political liability. In 2012, a Gallup poll found that 18 percent of Americans would not vote for a Mormon presidential candidate. Another poll that year indicated that 67 percent of white evangelicals said it was important for a presidential candidate to share the same religious beliefs. Romney mostly deflected questions about his faith and said he wasn’t running for pastor-in-chief.

But in a sense, he was. Because the United States is a comparatively religious country that eschewed establishing an official ‘Church of America’, the president serves as a sort of unofficial archbishop of American civil religion. That’s why still in 2020 only 60 percent of Americans say they would vote for an atheist presidential candidate.

The secular moment

However, openness to atheist candidates has been climbing steadily—up from just 18 percent in 1958—as more and more Americans identify as religiously ‘none of the above.’ In late 2012 the Pew Research Center released a ground-breaking report entitled Nones on the Rise, showing that one-fifth of the American adults no longer identified with a religion—equaling the proportion of the population that identified as evangelical. And the trend continues. A new Gallup poll found that church membership fell from 62% to 49% in just the past decade.

Much of the media commentary during the “nones” moment of the early to mid 2010s focused on the political inspirations and implications of widespread religious disaffiliation. Young people were leaving churches they viewed as right-wing and bigoted, and their departure would be a win for tolerance, reason, and pluralism.

But so far, emptying pews have not been good news for the tone of American political debate. In a recent article in The Atlantic, author and Brookings Institution senior fellow Shadi Hamid offered this analysis:

“if secularists hoped that declining religiosity would make for more rational politics, drained of faith’s inflaming passions, they are likely disappointed. As Christianity’s hold, in particular, has weakened, ideological intensity and fragmentation have risen. American faith, it turns out, is as fervent as ever; it’s just that what was once religious belief has now been channeled into political belief. Political debates over what America is supposed to mean have taken on the character of theological disputations. This is what religion without religion looks like.”

The return of the evangelicals

Rising secularisation has contributed to many white evangelicals’ feelings of cultural marginalisation and longings for the good old days. A shrewd salesman, Donald Trump effectively tapped into their feelings and longings. He did so primarily through the power of symbolism—meeting with prominent evangelical leaders, championing the phrase ‘Merry Christmas,’ promising to ban Muslims from entering the country, and signaling his support for the pro-life cause that is emblematic of a broader moral traditionalist worldview.

The surprise of Trump’s 2016 electoral victory, with the help of 81 percent of white evangelicals, brought renewed attention to the evangelical world—especially to the less mainstream segments of its broad tent such as Christian nationalists, prosperity gospel preachers, and charismatic groups focused on end times prophecy and spiritual warfare. A great many books and articles were written and lectures given to try to explain how a community that preaches honesty, modesty, and chastity could so fervently support—and even sacralise—a man who embodies the opposite of their virtues.

Despite the cultural limelight and political access many evangelical leaders enjoyed during the Trump years, the faith-fueled stridency, polarization, and ultimately violence that accompanied the evangelical moment revealed that evangelicalism lacks the capacity to serve as the civilizing, unifying, and stabilizing moral force that mainline Protestantism once was in American public life.

Joe Biden and the Catholic moment

With Joe Biden’s election, the focus has shifted to Catholicism and the role it plays within the broader culture. After being viewed as a foreign and even threatening faith for so much of American history, the Roman Catholic Church is now the spiritual home of 22 percent of the American population, 29 percent of the members of Congress, and two-thirds of the Supreme Court justices. This is a Catholic moment.

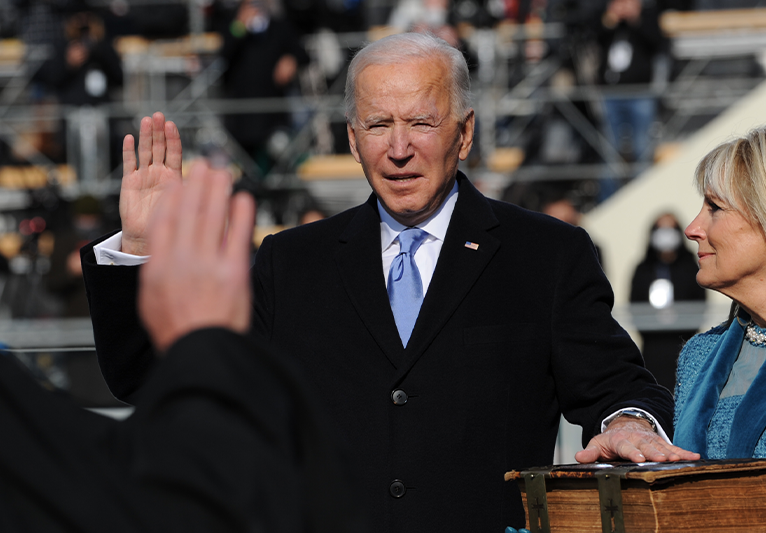

Biden’s inauguration in January showcased Biden’s personal devotion and the public’s acceptance of Catholicism. The new president quoted St Augustine, a young black Catholic writer delivered a stirring poem, a Catholic priest offered a prayer, and a Catholic Supreme Court justice administered the oath of office to Biden as he placed his right hand an on old Catholic Bible with a Celtic cross on its cover.

The incorporation of numerous Catholic individuals and elements into this quadrennial national ritual raised very little concern—on both the Left and Right. As David Gibson, the director of the Center on Religion and Culture at Fordham University, observes, ‘The sympathy for Biden’s Catholic practices may…signal a hunger among Americans for a genuine civil religion, one that unites rather than divides.’

Whereas Trump made instrumental use of religion to divide Americans (e.g. ‘I think Islam hates us’), Biden speaks with authenticity about how his particular faith inspires an inclusive vision. In an essay for a Christian Post last year, Biden said “My Catholic faith drilled into me a core truth—that every person on earth is equal in rights and dignity, because we are all beloved children of God.”

The two mottos on US currency—E Pluribus Unum (‘Out of Many, One’) and ‘In God We Trust’—speak to the religiosity, diversity, and aspiration for unity among the American people. The religio-political ‘moments’ of the past decade have been reminders that cultivating respect and fraternity among America’s diverse religious and non-religious communities remains an unfinished task. I’m a Protestant, but I hope Biden and his church will now seize the moment.

Note: This piece gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Religion and Global Society blog, nor of the London School of Economics.