As the Russian invasion of Ukraine enters its second week, our screens are filled with images of families separating and a country torn apart by war. Yet these divisions exist beyond our tv screens and economic sanctions. In this article, Lucian N. Leustean frames the conflict within the context of religious identity and a growing split within the Orthodox Church, which has been in the making since 1990. Leustean articulately explains the extent to which today’s war is a religious one and the implications it may have on the future of the global Orthodox Church.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is the first religious war in the 21st century.

At first sight, Russia and Ukraine are both predominantly Eastern Orthodox Christian countries. Ukraine is divided into two main Orthodox churches, the national Orthodox Church of Ukraine, which separated institutionally from the Russian Orthodox Church in 1990, and the Ukrainian Orthodox Church-Moscow Patriarchate, which remains the largest denomination in the country. However, the religious and political mobilization of the main actors show a different picture.

In 2018 and 2019, the Istanbul-based Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, the primus inter pares in the Eastern Orthodox world, recognized the autocephaly (independence) of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine. How could a Church receive national and international recognition in such a short period of time, namely between 1990 and 2019? Direct support of the Ukrainian political authorities towards the establishment of a national Orthodox Church only began to appear publicly after the 2014 Russian invasion of Crimea and the Donbas region. The wider societal mobilisation towards the new ecclesiastical structure can be seen in its military assistance. For example, the Ukrainian Ministry of Defence counted that, in 2014 and 2015, in administering the military troops on the Donbas front line, 295 clergy belonged to the Ukrainian Orthodox Church-Kyiv Patriarchate, 123 clergy to the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church and only 9 were from the Ukrainian Orthodox Church – Moscow Patriarchate. The Orthodox Church of Ukraine and the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, the largest denomination in the western part of the country, have regularly presented their pro-European Union and pro-NATO stance shadowing the discourse of the political authorities.

To what extent can Russia’s invasion of Ukraine be seen as a religious war and what might be its long-term impact? In religious terms, the war has been characterised by three key features, namely intensity, human security and the emergence of a new world branch in Christianity.

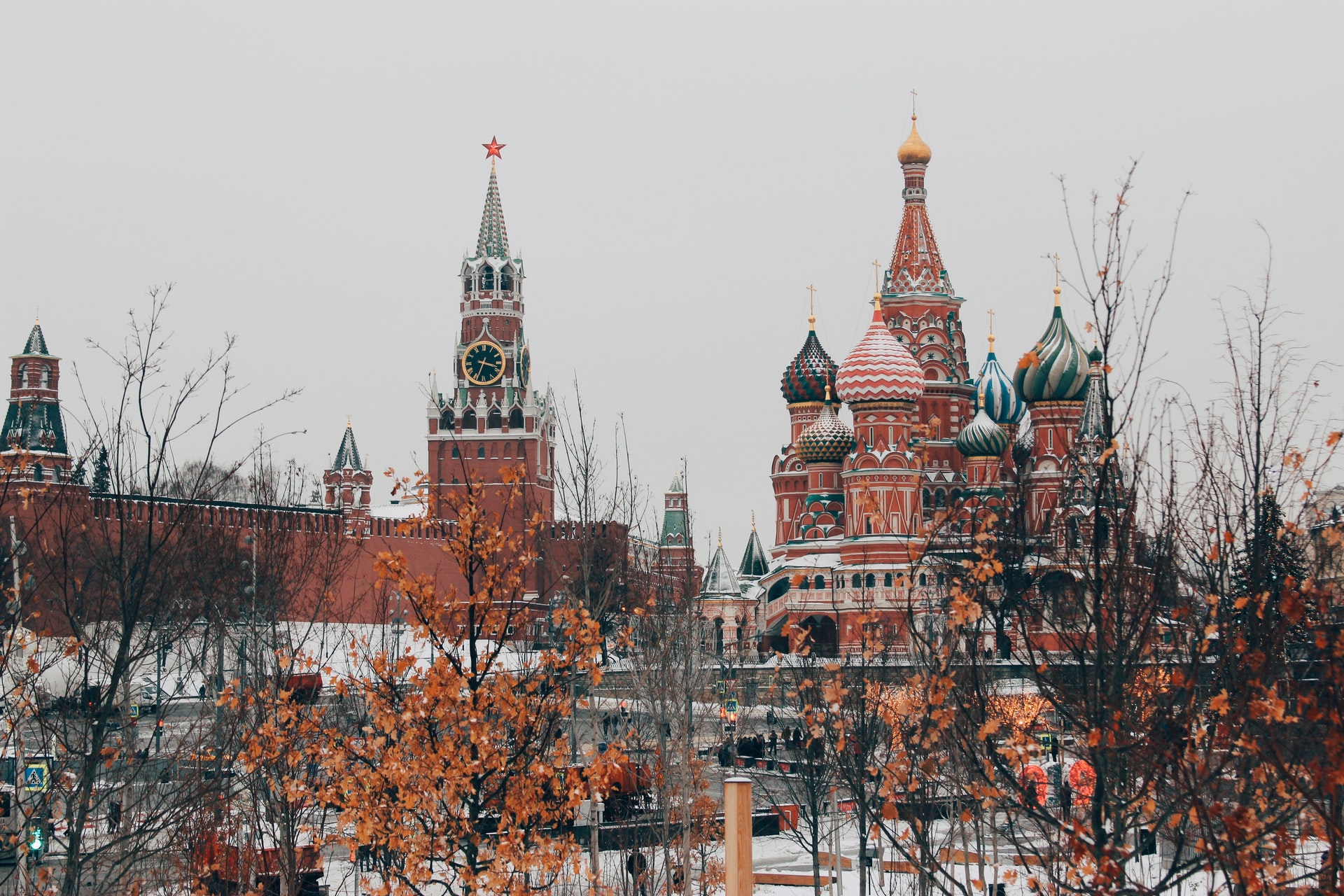

First, post-Second World War conflicts around the world have shown that when religion is involved, wars become more intense. Religious passions and eschatological visions of the material and spiritual worlds have a direct role in fostering violence. The close involvement of religion in anticipating the Russia-Ukraine conflict was summarised in President Vladimir Putin’s 2021 article ‘On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians’ in which he emphasized that Russia and Ukraine are ‘the same historical and spiritual space… The spiritual choice made by St. Vladimir, who was both Prince of Novgorod and Grand Prince of Kiev, still largely determines our affinity today’. Russians and Ukrainians were presented not only as the same people but also as sharing key religious figures and sacred sites, all of which are fundamental to their separate or shared identity and state formations. From the start of the military campaign, the political ideologization of religion has been evident in Russia’s advancement towards Kyiv, perceived not only as a government centre but also a key religious site.

Second, in the post-Cold War Eastern Europe and the former Soviet states, religious communities play a key role in engaging with populations in need through their own humanitarian networks. When states fail, religious communities are among the first to act as providers of human security. As the post-2014 conflict has shown, if the Russia-Ukraine war is prolonged, the Church which is best organised in addressing human security issues towards displaced populations and in working closely with the political authorities will attract an even higher support of the Ukrainian population. It is highly likely that the national Orthodox Church of Ukraine will continue to attract a larger number of faithful to the detriment of the Church under Moscow’s jurisdiction. There is even a suggestion that the latter should fully separate from Moscow and have its own autocephaly, dividing the Eastern Orthodox Church even further, particularly as a significant number of hierarchs refused to mention the Russian Patriarch Kirill in their services. Religious demography changes, transfer of parishes between the two Orthodox churches, and the attempt to implement a new status for key religious sites (Saint Sophia Cathedral, Saint Michael’s Golden-Domed Monastery and Kyiv Pechersk Lavra) will only increase violence and emphasise the religious nature of the war.

Third, in positioning themselves in the conflict between the Moscow and the Ecumenical patriarchates, Orthodox clergy outside Ukraine have suggested that, for the first time, the autocephaly recognition of the Russian Orthodox Church should be revoked. This decision would be in response not only to Russia’s war in Ukraine but more broadly due to the ways in which the Moscow Patriarchate projects the Kremlin’s world geopolitics. An example was the Holy Synod’s decision to set up a ‘Patriarchal Exarchate in Africa’ in December 2021 to bring together religious communities who oppose Ukrainian religious independence and are currently under the jurisdiction of the Patriarchate of Alexandria. Two months later, the Exarchate seemed to attract over 150 clergy in twelve countries, a gesture which denoted the religious factor in advancing Russia’s influence in Africa. Disputes could even propagate from Africa to the Middle East with the Moscow Patriarchate setting up a parallel structure in Turkey bypassing the Ecumenical Patriarchate.

The implications could lead to churches refraining from using the word ‘Orthodox’ in their communication with the Russian Orthodox Church. The immediate implication would be that Christianity, as a world religion, will be divided even further by acquiring a new branch, namely Roman Catholicism, Protestantism, Eastern Orthodoxy and ‘Christian Traditionalism’ for the Russian Church and those supporting its stance in Ukraine in the latter. The Orthodox Church of Ukraine would thus replace the Russian Orthodox Church in the Eastern Orthodox world while the Moscow Patriarchate would move further outside communion with fellow churches in setting up its own ecclesiastical jurisdictions around the world.

In sum, the longer the conflict takes the wider the religious involvement will become. In finding a diplomatic solution, the Ukrainian political authorities have suggested that a meeting should take place in Jerusalem demonstrating that religion is key not only in shaping conflicts but also in finding solutions. Religious diplomacy remains an unexplored avenue which could provide support not only to people in need but also to reaching diplomatic consensus.

This op-ed was supported by the author’s participation as Senior Fellow in the ‘Orthodoxy and Human Rights’ project, sponsored by Fordham University’s Orthodox Christian Studies Center, and generously funded by the Henry Luce Foundation and Leadership 100.

Note: This piece gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Religion and Global Society blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

1 Comments