As part of our Environment and Religion series, Mohd Amin Khan and Monika tell us more about why the Sarna religion is having a big impact on local conservation and the prevention of wildfires, and the risks they are facing. For these communities in India, the protection of indigenous religion and environment go hand-in-hand.

India is very diverse nation in terms of geography, ethnicity, culture, religious beliefs, distinct cultural values, and being home to approximately 1.5 billion people.

It is also home to around 104 million indigenous tribal people who follow their own rituals, cultural practices, beliefs, and religion. Many among them have moved into major religions such as Hinduism, Islam, and Christianity, while a significant number still follow their indigenous religions. Among them, Sarna stands out as one of the major indigenous tribal religions. As per the estimates derived from the Indian population census (2011), the population of those following Sarna religion in India are around 5 million, constituting a great number in scheduled tribe. The majority of Sarna followers reside in the forests and hilly regions of central and eastern India, primarily in the state of Jharkhand, though there are also smaller populations in other states such as Chhattisgarh, Bengal, Odisha, and Bihar.

The term “Sarna” is derived from the Mundari word for sacred groves, which are an integral part of Sarna religious practices. The Sarna religion is deeply rooted in nature worship, and its followers maintain a strong connection with natural elements such as forests, rivers, and hills, which are regarded as sacred entities. The Sarna followers celebrate various rituals and festivals to please deities associated with natural elements. It is a religion based on an oral tradition where the knowledge and beliefs are transmitted through myths, stories, and rituals due to lack of any written scripture.

Sarna Religion and Environmental Conservation

Sacred groves and their significance

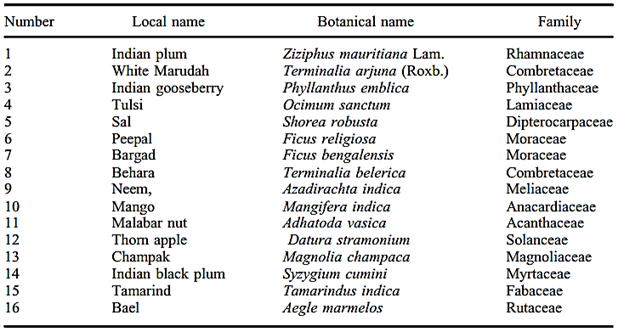

One of the prominent features of the Sarna religion is the worship of sacred groves. These are the patches of forests considered sacred, where no harm is allowed to the trees and wildlife. Sacred groves have garnered significant recognition due to their ecological, historical, cultural, and religious significance. The traditional beliefs of the Sarna followers are that if you harm the sacred trees, it will lead to misfortune, disease, and disaster for the community. Therefore, such kinds of beliefs and cultural practices of Sarna indigenous tribes promote the conservation, regeneration, and prevention of wildfires. The major examples of sacred groves (trees/plants) are as follows:

Table: List of major sacred groves (Singhal et al 2021)

Religious belief, festivals, and ritual ceremonies promoting conservation

The nature-centric traditional festivals and rituals of Sarna tribal communities play a significant role in the conservation. The Sarna followers take oaths of protecting the nature i.e. land, river, and forest during their festival celebrations and transfer these traditions and cultural practices to the upcoming generations in order to save the environment for the future generation.

Marriage ceremonies

Sarna followers conduct their marriage ceremonies beneath the canopy of revered trees such as Sal (Shorea robusta), Karam (Adina cordifolia), Amla (Emblica officinalis) and Kendu (Diospyros melanoxylon), considering them sacred entities. Symbolising their significance, bhelwa (Semecarpus anacardium), mango, bamboo, and sidha (Legerstromeia parviflora) branches are planted at the marriage site. Sal leaves are utilised for ceremonial worship, serving as leaf cups and plates. Each sacred tree holds distinct beliefs: mango symbolises the continuity of descendants, bamboo represents reproduction, sidha signifies loyalty between spouses, bhelwa provides protection from the evil eye, and mahua is linked to love in marital relationships. The inclusion of these trees is integral to the completeness of the marriage ritual. The marriage ceremony is deemed incomplete without the inclusion of sacred trees and plants in the ritual. These enduring traditional practices are the inherent parts of Sarna culture and considered favourable and balanced measures for the protection and conservation of flora and fauna in their natural habitat.

Sarhul festival

Sarhul is a festival that celebrates the interconnectedness of nature and humanity, highlighting the significance of environmental conservation and harmonious coexistence with the Earth. It is observed in the months of March and April, during which Sarna tribes engage in worship of the Sal tree. The Sal tree holds sacred significance among tribal communities and it is revered during the festival. Individuals present rice, flowers, and fruits as a gesture of reverence towards the tree. During the festival time, tribes refrain from harvesting any part of the Sal tree and contribute to the enhanced regeneration. Consequently, they are also protecting Sal and other associated trees from fires since wildfires also peak during these months.

Fig: People performing Sarhul festival in Jharkhand, India

Karam festival

The Karam festival centres around the veneration of the Karam tree (Adina cordifolia) and is celebrated in October. The festival aims to enhance the agricultural yield. Karam festival is a prominent example of tree worship practiced by Sarna followers in the central and eastern regions of India. During the Karam festival, people worship Karamsani, represented by a special twig called Karma dal. Karamsani is considered the goddess of plants, fertility, and destiny. An interesting aspect of the festival is the intentional protection of the Karam tree (Adina cordifolia) and its related species. Sarna tribes avoid cutting down the Karam tree until the festival season, thus playing a crucial role in preserving and regenerating these trees.

Fig. People worshipping Karam tree during the Karam festival

Faggu

Faggu is celebrated with the aim of ensuring a bountiful crop on the full day of the month of Phagun (March-April). Prior to this day, young boys and other members of the village gather firewood, hay, dry grass, and dry leaves at a designated spot in the village. On the full day of Phagun, they assemble, and the village priest (Pahan) conducts a worship ceremony before setting fire to the hay with the hope of a prosperous crop. During this period Sarna tribes collect dry wood and leaves from the forests, and remarkably this practice occurs at a time when the risk of wildfires is high across the country. The act of gathering these dry materials by the tribes reduces the fuel load, significantly lowering the likelihood of wildfires. Consequently, this festival plays a crucial role in preventing or mitigating the initiation of wildfires and contributes significantly to the conservation of the forest ecosystem.

All of the above-mentioned festivals, each carrying significant beliefs of the Sarna religion, are celebrated throughout the year. Sarna philosophy revolves around a profound connection with nature and a commitment to peaceful coexistence, referring to nature as “mother” and worshiping it. The Sarna religion actively promotes environmental conservation and emphasises practices that foster harmony with nature.

Sarna Religion in a Modern Context

In recent times, the Sarna community has increasingly found common ground with modern conservation efforts. The sacred groves, once preserved solely based on traditional beliefs, now attract attention from environmentalists, scientists, and conservationists. Collaborations have emerged to study the rich biodiversity within these groves and understand how indigenous practices contribute to ecological balance. Conservation organisations and Sarna communities have joined hands to develop strategies that merge traditional knowledge with modern scientific approaches. The unique rituals and practices observed during festivals have become subjects of interest for researchers seeking sustainable conservation models.

The combination of Sarna traditions with modern technology reflects a dynamic response to conservation challenges. While sacred groves remain central to Sarna philosophy, technology is used to document and share knowledge about these practices. Digital platforms educate a broader audience on the significance of sacred groves, fostering understanding of Sarna environmental values. In environmental monitoring, Sarna communities embrace tools like satellite imaging and data analytics to assess grove health and target conservation efforts. This integration allows for a strategic approach to protection, complementing traditional methods. However, balancing tradition and technology requires careful consideration to preserve Sarna core values. Sarna religion serves as a unique example of how ancient traditions can collaborate with contemporary environmental awareness and technology.

Major Obstacle: Fight For A Legal Recognition

Over the past decade, Sarna followers across the country have been consistently struggling for the official recognition of their religion within the Indian constitution. This plea arises from the need to safeguard their distinctive culture, traditions, and faith from conversion into mainstream religions. The rapid rise of capital-oriented development has led to the Sarna community feeling left behind, making them susceptible to conversion by mainstream religions under the guise of socio-economic upliftment. The absence of a specific religious code for them in the Indian constitution fuels their ongoing protests, as they strive for constitutional recognition to preserve their pristine culture, traditions, and their identity.

Conclusion and Future Prospects

Indeed, Sarna practices hold a great significance towards environment conservation and creating sustainable ecosystem practices. Sarna offers a unique perspective on the harmonious coexistence of humanity and nature, providing valuable insights for modern environmentalists. The sacred groves, various cultural festivals, worshipping of nature, and work on their conservation each present a model for sustainable environment management that could be applied beyond the confines of the community. In this case, conservation organisations and policymakers have a valuable opportunity to collaborate with the Sarna community to integrate these time-tested practices into broader conservation strategies. As societies seek innovative and culturally sensitive approaches to conservation, the Sarna-inspired practices stand ready to contribute to a more sustainable and interconnected future.

It is really a thought-provoking article that reveals the rich religious ethos of the Indian indigenous tribal who strongly supports the sustainability and peaceful coexistence between nature and humans.