The Covid-19 pandemic (and its multiplying implications on people’s purchasing ability and their willingness to spend money) and climate change (more frequent extreme weather and severe impact) have also contributed to the overall formula of living on the edge of Jakarta as socially and spatially marginalised communities in the 2020s, writes Naimah Lutfi Abdullah Talib.

_______________________________________________

Complex logistical infrastructure has been an integral part of modern human lives, regarded as the blood vessel for the mobility of goods, humans, and capital. An important part of an integrated and complex logistical system is its physical infrastructure, which contains and enables the material circulation of goods. Among these are ports. Scholars have examined the political economy that underpins the processes of making megaprojects, including large-scale ports, and the socio-economic and ecological impacts on local and indigenous communities (Chua et al., 2018; Cowen, 2014). While we imagine that mega infrastructure projects are something majestic and often out of touch, it took decades to plan, design, ‘acquire’ the land, and construct it. At the same time, when we talk about mega infrastructure projects, dispossession and displacement are major social injustices resulting from the appropriation of the use of space, which is mostly state-facilitated and large-corporation or investor-backed activities. In other words, alongside the years of ‘making space for mega infrastructure’, there are often people who have been living and making their livelihoods there for decades. As part of my PhD study, I attempt to understand how local communities in mega-urban areas, with diverse characteristics and vulnerability contexts, navigate megaprojects-in-the-making in their neighbourhoods. Departing from critical logistics studies and urban studies, I raise the question of what happens with communities who are not directly and physically displaced when megaprojects take place in their neighbourhoods, or what Magaramombe (2010) calls ‘displaced in place’? What if the process takes a long time, following the cycle of the project and uncertainties within it? How do they navigate the situation?

The busy bay of Southeast Asia

As one of the fastest rebounding economies after the 1998 Asian financial crisis and driven by ambitious human development agendas in Southeast Asia, Indonesia has been trying to foster its connectivity within the archipelagos, while further integrating into the regional and global economy (Suwandi, 2019). The imaginary of connectivity was translated into state-orchestrated logistical infrastructure, believed to enable a more integrated economy and social system within the country. Logistics have been embedded into the larger narrative and national policy agenda of advancing economic development, reducing economic gaps amongst regions (Java and Eastern-Indonesia) (Amin et al., 2021) and promoting social welfare in the outermost regions/ islands (Cabinet Secretary 2014). Problems occurred when the ends appropriated the means at the cost of socially and spatially marginalised communities, as mega ports emerged without meaningful opportunities for communities to participate in decision making.

Jakarta bay is a busy place, both metaphorically and in reality. Peter J. Rimmer and Howard Dick on “Gateways, Corridor, and Peripheries”, Jakarta is one of the main gateways in Southeast Asia and interconnected into a global corridor. Seventy-five per cent of the physical export-import activities recorded in Indonesia take place in Tanjung Priok Port, with an import value of 56.1 million USD or almost 40 per cent of the country’s total import value. The heavy flow of freight goods into and out of the country is now shared with the recently developed phase-1 New Priok Port, just seven kilometres from Tanjung Priok Port. The role of sea transport and logistics, especially in Jakarta bay, could be traced back to colonial times when Tanjung Priok Port was part of the Dutch colonial-led infrastructure to manage the flow of spices and other natural resources extracted from parts of now-Indonesia for use in Europe.

My research started in mid-2020 without having specific questions in mind when I undertook a scoping study in Kalibaru, Cilingcing subdistrict, North Jakarta. My interests revolve around human interactions with their surrounding environments, including the question of justice. Following the changing environments, I seek to understand who, under what circumstances, and to what extent can (and cannot) adapt, cope, and resist.

While New Priok Port has been planned since the early 2010s, the first development phase was completed in 2018 and is now under preparation for phase 2. Economic displacement and a sense of insecurity due to the risk of physical displacement have been observed in this subdistrict since 2017 and documented by Delphine et al. (2019). By the end of 2019, approximately 250 households on the edge of the coast were displaced. While the land was formally registered under the Indonesia Port Corporation (PELINDO II), most of these households have been residing there for at least a decade and relied on ocean-based activities for their livelihoods. By the time I did my fieldwork, commencing in late 2020, I had observed the changes in the neighbourhood. I conducted in-depth, and to some, multiple interviews and focus group discussions with community members in Kalibaru. Many of the displaced households managed to find a unit/ studio room in the neighbourhood. Staying there, a shared response from the fisherfolks enables them to continue making a living from the ocean using their skillsets and assets (the small boat of 5 to 15 GT). Noting that not all own boats, fisherfolks are more comfortable with the idea that they can still work with the ‘boss’ (boat owners) to fish in the sea, process the fish, or do other ocean-based supporting activities.

Households who experienced physical displacement received compensation equal to a 12-months cost for renting a kost (informal studio-style apartment unit, often shared-bathroom) in the neighbourhood and were allowed to collect materials from their house for re-use or re-sell. However, a few households, such as one female-headed household and two elderly-headed households, did not receive compensation as they were renters (only the owners of the structures received the compensation). Evicted people have had to bear the additional financial cost of monthly rents (ranging from 250k IDR to 750k IDR), which took up 50 to 60 per cent of their unpredictable monthly earnings from multiple economic activities.

The Covid-19 pandemic (and its multiplying implications on people’s purchasing ability and their willingness to spend money) and climate change (more frequent extreme weather and severe impact) have also contributed to the overall formula of living on the edge of Jakarta as socially and spatially marginalised communities in the 2020s.

Micro-infrastructures as a form of resistance

A direct impact on fisherfolks in Kalibaru was the closure of access to the ocean as reclamation started in 2019. The closure was gradual over a year and left one point of access to the fish auction market. Ships wait in line to undock fish, which takes more time than usual, meaning they need more ice to keep the fish fresh and less resting time to be on standby mode for their turn.

In response to this, the community came up with an idea to build wooden bridges made from bamboo (jembatan bambu) connecting the shoreline edges of Kalibaru so that small-scale fishing boats could dock/ park along the bridges and have direct access to the sea. The interviewed fisherfolks explained that they asked the contractor to temporarily allow them to build this bridge. At the same time, internally, the communities chipped in to buy the bamboo and other materials needed to construct these bridges circling the bay area of Kalibaru, which is up to 2.5 km long. The bridges have been in place, well-functioning and serving most of the communities, for at least 18 months now. One female-headed household who is also a micro salty-fish producer explained how she used this bridge every day to get ‘a cheaper’ price for the fish, directly in the docking place, before the fisherfolks reach the formal/ fish auction market. For the fisherfolk, selling the fish directly to salty-fish producers saves time and manpower costs (kuli panggul). For the micro fish processors, the price in the boat-docking facilitated by the wooden bridge is slightly lower compared to when it reaches the fish auction market.

Communities exercising their agency through (re)making space that has been dispossessed from them. The activities of planning, consolidating grassroot resources, and construction of the wooden bridge can be seen as a form of nonviolent everyday resistance. Despite the outcomes deemed to be not fully just, communities have carefully calculated what is feasible and what works for them , given the constrained social, economic, and political situations under this neoliberal-policies and regulations regime. For some people, these bridges bring hope and enable them to continue accessing the sea and the alternative market. The act of planning, organising and constructing wooden bridges is non-violent everyday resistance, part of what Asef Bayat powerfully coins as “quiet encroachment” in Life as Politics, which “refers to noncollective but prolonged direct actions of dispersed individuals and families to acquire the basic necessities of their lives (land for shelter, urban collective consumption or urban services, informal work, business opportunities, and public space) in a quiet and unassuming illegal fashion” (p.45). Yet, it is important to note that this bridge is temporary and appropriated relative to the mega project cycle, an indication of the limitations of working with what is politically feasible and socially acceptable.

This grassroots resistance was produced and may operate under certain conditions involving social, political, and cultural capital operators across scales. Taking Kian Goh’s (2021) question, which echoed critical theorists and feminist scholars, in the future, I seek to explore not only the form of resistance but also the underlying conditions that enable this resistance to occur and if we can call it adaptation. Will it be the presence of democratic space to contest ideas, as suggested by Nancy Fraser, as the foundation for justice to thrive? Will it be a condition where a certain minimum human capability has been reached to seize opportunities, as suggested by ? Finally, exercising agencies at the level of communal, households, and individual, in a smaller and rather quiet way but sustained enough to make it happen, could be seen as a form of non-violent resistance in the everyday life of coastal communities.

References

Amin, C. et al. (2021) ‘Impact of maritime logistics on archipelagic economic development in eastern Indonesia’, The Asian Journal of Shipping and Logistics, 37(2), pp. 157–164. doi:10.1016/j.ajsl.2021.01.004.

Bayat, Asef (2010), Life as Politics: How ordinary people change the Middle East, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. Available online: https://scholarlypublications.universiteitleiden.nl/access/item%3A2882444/view

Cabinet Secretary (2014) Optimalisasi Pembangunan Tol Laut Untuk Memperkuat Sistem Logistik Kelautan Nasional, Sekretariat Kabinet Republik Indonesia. Available at: https://setkab.go.id/optimalisasi-pembangunan-tol-laut-untuk-memperkuat-sistem-logistik-kelautan-nasional/ (Accessed: 12 December 2020).

Chua, C. et al. (2018) ‘Introduction: Turbulent Circulation: Building a Critical Engagement with Logistics’, Environment & Planning D: Society & Space, 36(4), pp. 617–629. doi:10.1177/0263775818783101.

Cowen, D. (2014) Deadly Life of Logistics: Mapping Violence in Global Trade. Minneapolis, UNITED STATES: University of Minnesota Press. Available at: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unimelb/detail.action?docID=1765501 (Accessed: 25 August 2021).

Delphine et al. (2019) ‘Living on the edge: Identifying challenges of port expansion for local communities in developing countries, the case of Jakarta, Indonesia’, Ocean & Coastal Management, 171, pp. 119–130. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2019.01.021.

Fraser, N. (2009) Scales of Justice: Reimagining Political Space in a Globalizing World. Columbia University Press.

Harvey, D. (2012) ‘The “New” Imperialism: Accumulation by Dispossession | Taylor & Francis Group’, in Karl Marx. 1st edn. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. Available at: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315251196-10/new-imperialism-accumulation-dispossession-david-harvey (Accessed: 21 June 2021).

Indonesia Bureau of Statistics, Badan Pusat Statistik (2021). Available at: https://www.bps.go.id/publication/2021/12/17/263c926c00f487d8ebf88236/impor-menurut-moda-transportasi-2019-2020.html (Accessed: 5 May 2022).

Magaramombe, Godfrey. (2010). ‘Displaced in Place’: Agrarian Displacements, Replacements and Resettlement among Farm Workers in Mazowe District. Journal of Southern African Studies. 36. 361-375. 10.1080/03057070.2010.485789.

Rimmer, Peter J and Dick, Howard (2019). ‘Gateways, Corridors, and Peripheries.’ in Routledge Handbook of Urbanization in Southeast Asia, edited by Rita Padawangi. Routledge: Taylor and Francis.

Suwandi, Intan 2019, ‘Value Chain: the New Economic Imperialism’, Monthly Review Press, New York.

Terminal Kalibaru – Tanjung Priok Jakarta | Indonesia Investments (2017). Available at: https://www.indonesia-investments.com/id/proyek/proyek-publik/terminal-kalibaru-jakarta/item319 (Accessed: 14 March 2021).

______________________________________________

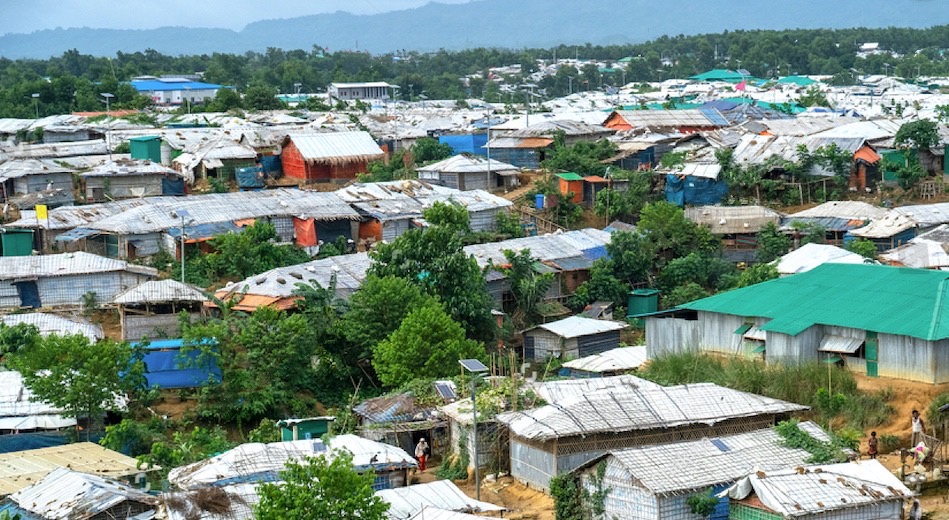

* Banner image is copyright of the Author.

*The views expressed in the blog are those of the authors alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre or the London School of Economics.