The First World War seems to be part of a distant past for most Bengalis, with the new generation of UK’s Bengali diaspora being left out of the nation’s collective memorialisation. A more inclusive remembrance of the First World War is required to address this, writes Ansar Ahmed Ullah, who recalls Bengal’s contribution during World War One.

The First World War seems to be part of a distant past for most Bengalis, with the new generation of UK’s Bengali diaspora being left out of the nation’s collective memorialisation. A more inclusive remembrance of the First World War is required to address this, writes Ansar Ahmed Ullah, who recalls Bengal’s contribution during World War One.

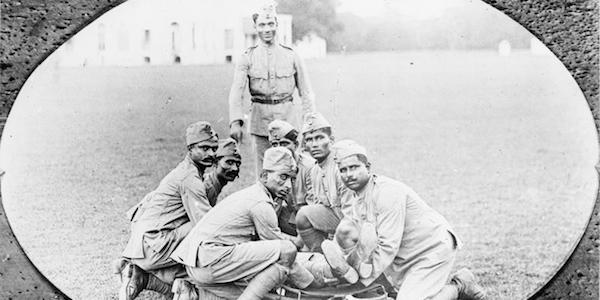

At present the UK is commemorating the Centenary of the end of the First World War. This research, supported by Big Ideas and the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) is part of ‘The Unremembered’, a project commemorating the bravery and sacrifice of the Labour Corps throughout the First World War during which the Indian army provided the largest volunteer army in the world.

During the War Britain had called on its Empire and 1.5 million Indian soldiers and 1.3 million Canadians, Australians, New Zealanders and South Africans fought on the allied side. For many memories of the war are kept alive either through their own family history and local communities. Because of its long-term impact on society and the world we live in today, nations, communities and individuals across the world have for the last three years come together to mark, commemorate and remember the lives of those who lived, fought and died in the First World War. The UK Bengali community however, seems to be indifferent towards the commemoration.

Throughout the duration of the First World War, of the 1.5 million Indian men who served, tens of thousands were labourers – in fact, more than half a million (563,369) served in non-combatant roles, deployed in the Indian Labour Corps. They travelled with the military providing food, water and sanitation for soldiers and army animals, carrying ammunition to the frontline. They built hospitals and barracks, docks and quays, roads, railways and runways; cared for horses and mules; maintained and repaired tanks; fitted electric lights; cut wood; and made charcoal. They were also recruited to undertake the massive task of building modern docks and infrastructure from Basra to Baghdad ensuring the success of the Mesopotamia campaign.

Even when the war stopped the work of war continued. After, the war labourers remained on the battlefields removing weaponry and ammunition, carrying the wounded and nursing the sick, retrieving the dead and creating war cemeteries. Most of the Indian Labour Corps deaths on the Western Front were due to cold weather and illness. They served on the Western Front of France and Belgium; Iraq; Gallipoli in Turkey; Iran; Caucasus; Salonica in Greece; the Middle East, East Africa; and in Afghanistan. Indian labourers worked with the British, South Africans, Chinese, Canadians, Australians and Egyptians – to name some of the countries involved. They were First World War’s army of workers, today all are but forgotten. They are The Unremembered.

From the German invasion of Belgium in August 1914, the battles of the First World War spread across the world from Africa to the Far East, the Middle East to the North Atlantic, the war was global. The British and Allied Forces struggled to cope with the demand for manpower after the huge losses of men during the Battle of the Somme in 1916. A million men on both sides died or were wounded or captured during 141 days in 1916. The Indian Labour Corps arrived in Marseilles, France from June 1917. Some 50,000 men served in France and Belgium from 1917 to 1920. More than 15,000 were still present in 1919, allowing the British army to demobilise more quickly.

From India, more than 100,000 men of the Indian labour Corps with Porter Corps and Jail Labour Corps served in France and Iraq. More than 3000 men from the Indian Labour Corps died in Basra during the Mesopotamia campaign. The role of the Indian Labour Corps in the Mesopotamia campaign deserves special focus since it was in Mesopotamia that the most Indian Labour Corps’ lives (11,624) were lost.

There are 1,494 Indian Labour Corps graves in France, from the Western Front – where they served, to Marseilles – the port of arrival and departure. There are 1,174 Indian Labour Corps names written on the India Gate memorial in New Delhi. From the Indian state of Manipur, 2000 men joined the Manipur Labour Corps of whom 500 died in service. The British War Office gives a figure of 17,347 who died on various Fronts.

While most of the Labour Corps were not exposed to the dangers of the frontline they could get caught by medium and long range enemy artillery and sometimes even gas attacks. Many also died during the long journey to the battlefields, and most of all from illness during their service, especially from Spanish Flu pandemic and pneumonia. Those serving in the Mesopotamia campaign worked in the terrific heat of up to 48°C. In France the winter of 1917-1918 was bitterly cold, and respiratory disease caused suffering and deaths. Cold conditions, old huts, relentless work took their toll. The winter saw high numbers of deaths from pneumonia in France.

The Basra Memorial in Iraq commemorates 11,000 labourers amongst 33,000 Indian forces. Amongst the Indians there are thousands of Bengali names. For example, a couple of names point to present day Bangladesh, Rahim Ullah, son of Jakim Muhammad of Kanalpur, Sylhet and Rahman Ali, son of Yusuf Ali of Kashimpakh, Comilla, Tippera.

In addition to Labour Corps, Indian seamen served on board marine transports, hospital ships and as part of the river flotilla in Mesopotamia. They also served on ships that carried out patrolling in the Bay of Bengal, Arabian Sea and on mine sweeping duties in Indian waters around defended ports.

The 49th Bengalis Memorial Kolkata, memorial pays tribute to a remarkable unit. The 49th Bengalis was the only army unit to be composed entirely of ethnic Bengalis. Raised in 1917 and disbanded in 1922, it was deployed on active service in Mesopotamia. Bangladesh’s national poet Kazi Nazrul Islam had served in this regiment. He had joined the British Indian Army in 1917 at the age of eighteen. Nazrul Islam while serving in the army composed and wrote his first published poem Mukti in Karachi Cantonment.

During the First World War, the British had created a Double Company with men from Bengal in its armed forces. Later this Double Company was renamed and became the 49th Bengalee Regiment. The 49th Bengalis were trained in Karachi and despatched to Mesopotamia in August 1917, reaching there in September. The regiment was raised, despite the British having by then categorised Bengalis as a non-martial race. Some historians argue that the British temporarily abandoned the martial race theory to accommodate the Bengalis because of the manpower they needed to overcome the massive losses at the beginning of the War in Mesopotamia. The 49th were put on guard duties at the Tamminah Royal Air Force base. They were part of the Indian Expeditionary Force “D” to be deployed in Mesopotamia against the Turkish. An estimated 32,000 officers and soldiers, most of them Indian, died in Mesopotamia.

One of the reasons why Bengalis seem to be so indifferent to the commemoration could be because for most Bengalis from Bangladesh, history starts with the Bangladesh War in 1971. The First World War seems to be part of a distant past for most Bengalis. And of course, the state of Bangladesh didn’t exist during the First World War but was part of a greater India. Therefore, all commemorations dating prior to 1947 only mention India and to an extent, Pakistan. Bangladesh doesn’t get a mention in these commemorations. Hence, most Bengalis aren’t even aware of Bengali participation in the First World War.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission website databases are composed of documents recording the details and commemoration location of every casualty from the First and Second World War. One of the problems of finding Bengalis in that list is since Bangladesh as a state did not exist during First World War and secondly many of the Bengali spellings of soldiers, towns and cities of Bengal and Bangladesh have also changed. However, a Bengali with a sharp eye should be able to locate Bengalis within the armies of the First World War. Indeed, a search for Bengali Labour Corps provides thousands of Indians including Bengalis from today’s Bangladesh and Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura, who served in Indian Labour Corps, 49th Bengalis, Inland Water Transport Royal Engineers, Indian Railway Department, Indian Postal and Telegraph Department, Indian Survey Department and the Indian Merchant Service.

The new generation of UK’s Bengali diaspora are being left out of the nation’s collective memorialisation. The UK Bengali community could be engaged in the Centenary memorials by involving them as key stakeholders. Centenary events that recognise and celebrate the memory and contributions of all communities, including the Bengali community, could foster more of an inclusive remembrance of the First World War.

This article originally appeared on Big Ideas and has been edited for length and republished with permission.

This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

About the Author

Ansar Ahmed Ullah is a community activist who has lived and worked in the East End of London since the 1980s. He has worked as a youth, social and community worker and has been an active anti-racist campaigner. He is currently involved with the Swadhinata Trust, set up in 2000 to engage and work with young people to promote secular Bengali heritage and arts.

Ansar Ahmed Ullah is a community activist who has lived and worked in the East End of London since the 1980s. He has worked as a youth, social and community worker and has been an active anti-racist campaigner. He is currently involved with the Swadhinata Trust, set up in 2000 to engage and work with young people to promote secular Bengali heritage and arts.