On Thursday the House of Representatives voted to approve a budget bill that, once passed by the Senate, will avoid the threat of another government shutdown in 2014. Roy Meyers takes a close look at the deal, which includes some higher ceilings for appropriations over the next two financial years, as well as some minor savings. He argues that the agreement symbolizes a “time out” from major budgetary conflicts between Democrats and Republicans, in anticipation of primary and general elections next year.

On Thursday the House of Representatives voted to approve a budget bill that, once passed by the Senate, will avoid the threat of another government shutdown in 2014. Roy Meyers takes a close look at the deal, which includes some higher ceilings for appropriations over the next two financial years, as well as some minor savings. He argues that the agreement symbolizes a “time out” from major budgetary conflicts between Democrats and Republicans, in anticipation of primary and general elections next year.

The U.S. Congress, long known for the high frequency of elections to this body, has more recently become famous for the infrequency with which it adopts budgets. These related features are central to interpreting the budget deal that just passed the House, and that will pass the Senate soon.

The agreement is very simple. It sets separate ceilings for defense and non-defense appropriations for fiscal year 2014 (FY14–the current year, which began on October 1) and fiscal year 2015 (FY15). These new ceilings are higher than the existing “sequestration” ceilings that would be enforced on January 15 of each fiscal year. This adds $22.4 billion each to defense and non-defense categories in FY14, and $9.2 billion each in FY15.

The deal offsets these spending increases with a collection of minor savings, most of which would occur in the years following FY15. It extends for 2 years, into 2023, the sequestration ceilings on selected mandatory programs such as Medicare, and user fees for customs and border protection. It tweaks several fossil fuel programs and makes retirement programs slightly less generous for federal civilian new hires and early retirees from the military. It increases fees for airline passengers and premium rates for the Pension Benefit Guarantee Corporation. The deal does not include provisions that had been widely rumored, such as revenues from wireless spectrum auctions or extension of benefits for the long-term unemployed. The legislation thus is a rare combination of a rudimentary budget resolution and a very small reconciliation bill.

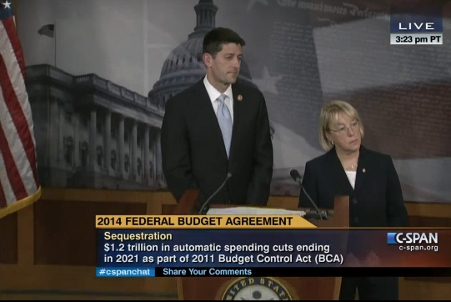

Not a person in DC prefers this agreement over alternatives, but many believe this is the best that can now be done. Though pragmatism informed by an understanding of institutional realities has often been absent in recent years, the lead negotiators, Democratic Senator Patty Murray and Republican Representative Paul Ryan, both argue that the deal represents visible proof that the two parties can cooperate. This is further evidenced by its formal title, the “Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013.”

Coming just two months after a foolish government shutdown caused by the antithesis of bipartisanship, the current budget agreement must be seen as an effort in reputation repair. This is particularly the case for many Republicans, who having forced the shutdown by arguing that it would lead to repeal of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and/or the reduction of government spending, deservedly bore the majority of blame for the shutdown’s costs. Rep. Ryan thus supplemented his praise for the deal by emphasizing its deficit reduction effects (a minuscule $23 billion over ten years) and its elimination of the threat of another shutdown. If his colleagues stick to this position, this implies that the need to yet again raise the debt ceiling sometime in spring 2014 will not be another exercise in brinksmanship.

The potential success of this repositioning for the upcoming elections will depend on the extent to which the electorate forgets what has happened since the 2010 midterms, when Republicans regained control of the House. In 2011, the impasse between the parties led to adoption of the Budget Control Act, which created the budget “supercommittee” (which failed to reach agreement) and the sequestration ceilings. 2012 saw the re-election of both President Obama and the House majority, and just after the new year arrived in 2013, increases in tax rates for those with high incomes. This was followed in several months by the first sequestration, and by the House and Senate adopting budget resolutions in mid-March. Though House Republicans had justifiably criticized Senate Democrats for not producing budget resolutions in previous years, they refused to go to conference with the Senate absent a pledge that tax increases be taken off the negotiation agenda. The two bodies were also far apart on FY14 appropriations levels, with the Democrats at $1.058 trillion, and Republicans at $967 billion (with all their cuts coming from non-defense).

In this sense, the Bipartisan Budget Act is accurately named, for it almost exactly splits that difference on the appropriations total, landing at $1.012 trillion. It took nine months to reach that point, and succeeding months are unlikely to produce any more agreement on major budget changes. The Act includes provisions that would structure the appropriations process should the Senate and House fail to pass budget resolutions for fiscal year 2015, which would be a very good bet.

So now the Congress will be able to consider the regular appropriations bills for FY14, and then for FY15. As usual, passage of bills such as Labor-HHS and Interior will be delayed by partisan policy disputes. Farm programs will likely be reauthorized and a permanent fix to the flawed “SGR” system of adjusting Medicare provider rates seems to be in the offing.

Otherwise, this agreement symbolizes a “time out” from major budgetary conflicts in anticipation of the primary and general elections. The primaries will feature the ongoing civil war within the GOP between Tea Party and establishment forces. Yet anti-tax dogma is still dominant in the GOP, as represented by Rep. Ryan’s insistence that the revenue increases in the deal are “fees rather than “taxes.” Democrats, in turn, appear to be strengthening their opposition to entitlement savings options such as the “chained CPI.” The Bipartisan Budget Act may thus be more than a time out; it could be the practical end of the “grand bargain” illusion, at least for the next several years.

The other anticipated election is the midterm, and there health policy will be a major focus. Implementation of the ACA has been spotty at best, for a complex and ambitious law that was enacted on a partisan basis and has never been viewed positively as a whole by the public. On the other hand, the expansion of coverage is creating a new constituency for this spending, and the ACA’s incentives for restructuring the health services market appear to be helping reduce cost growth in this sector. Given that health budgets are a major challenge for the U.S., shifting the focus of the election towards the ACA’s various effects, despite the high potential for false characterizations of those effects, may be a benefit to the American people–especially when compared to the budgeting conflicts of the past several years.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1guz0CQ

_________________________________

About the author

Roy Meyers – University of Maryland, Baltimore County

Roy Meyers – University of Maryland, Baltimore County

Roy Meyers is a Professor at the Department of Political Science at the University of Maryland, BaltimoreCounty. His current research focuses on reform of the federal budgetary process, institutional concepts in budgeting, methods of priority-setting in budgeting and related processes, and attempts to limit earmarks.

1 Comments