Recent years have seen Chicago named the ‘murder capital’ of the U.S., echoing its past legacy as a ‘gangster city’. Andrew Papachristos argues that Chicago’s crime and murder rates are at an historic low, and that is nowhere near being the most violent city in the U.S. By analyzing 48 years of crime date from Chicago, he argues that crime is on a downward trend, and becoming more gang related. He also writes that these falls have been unevenly distributed geographically, and that a distinct crime gap remains.

Recent years have seen Chicago named the ‘murder capital’ of the U.S., echoing its past legacy as a ‘gangster city’. Andrew Papachristos argues that Chicago’s crime and murder rates are at an historic low, and that is nowhere near being the most violent city in the U.S. By analyzing 48 years of crime date from Chicago, he argues that crime is on a downward trend, and becoming more gang related. He also writes that these falls have been unevenly distributed geographically, and that a distinct crime gap remains.

When the FBI named Chicago the “murder capital” in 2012, they fixed the city with a label that was both misleading and open to interpretation. With 506 murders, Chicago did indeed log more homicides in a twelve-month period than any other city. However, the city’s homicide rate—the ratio of murders to population—was by no means the highest in the country. In fact, Chicago’s rate was four times lower than at least ten other major cities, including Baltimore, New Orleans, and Newark.

Chicago ended 2013 with 415 murders—fewer total murders in any single year since 1967. A bigger story, however, is that the overall crime and murder rates in Chicago are at historical lows.

It’s time we put statistics into context. This is the only way we can sharpen our focus on next steps to reduce violence and increase public safety. End-of-year totals are convenient figures for politicians and the media, but they do not tell the whole story. When thinking about crime, both time and history matter.

A report I recently completed at Yale’s Institute for Social and Policy Studies analyzed 48 years of crime data in Chicago to put some of these crime figures into context. When looking at nearly five decades of data, four important trends are worth noting:

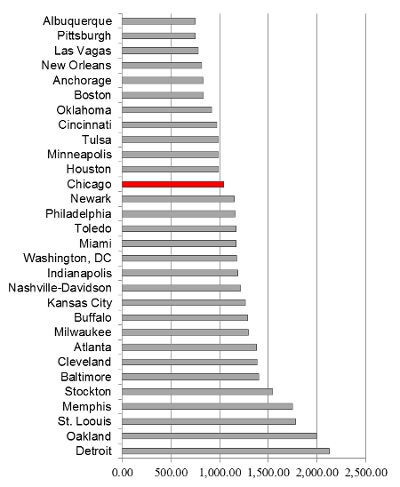

First, far from being the most violent city in the U.S., Chicago falls roughly in the middle of the nation in violence and murder rates. Figure 1 shows the violent crime rate of all U.S. cities with populations of 250,000 residents or more. Chicago, this figure clearly shows, is not the most violent city in the country. Rather Chicago’s rate of violent crime is almost half that of cities like Detroit, Oakland, and St. Louis.

Figure 1 – Top 30 Violent Crime Rates Across Major Metropolitan Areas with population of 250,000 or more residents (2012)

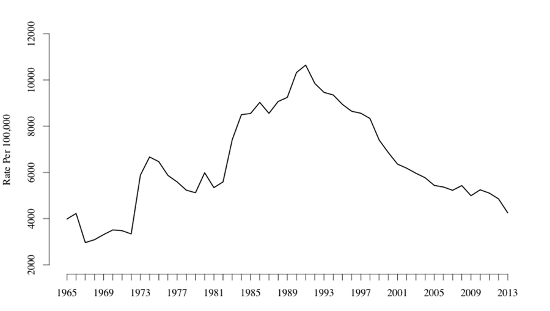

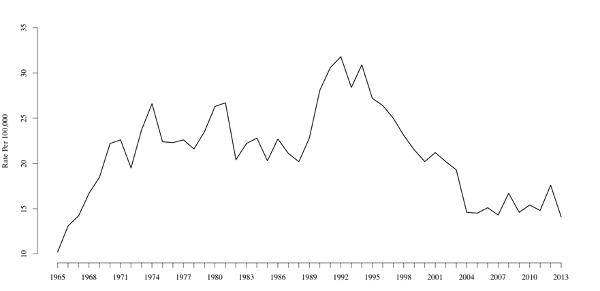

Second, Chicago is on track to have the lowest violent crime rate since 1972, and the lowest homicide rate since 1967. Figures 2 and 3 show the violent crime and homicide rate per 100,000 in Chicago over the last 48 years. Both of these figures show that Chicago—like many other U.S. cities—is experiencing some of its lowest levels of violence and murder in nearly five decades. And, the trend appears to be marching steadily downward.

Figure 2 – Index Crime in Chicago (rate per 100,000), 1965 to the present

Figure 3 – Homicide Rate (per 100,000), 1965 to 2013

Third, gangs have changed considerably over the last ten years. Chicago has been branded a “gangster city” since the days of Al Capone, regardless of the city’s murder rate. However, murders in Chicago are, on average, more likely to involve a member of a street gang than they were a decade ago. Also, today gang members are more likely to kill their allies and friends than their sworn enemies.

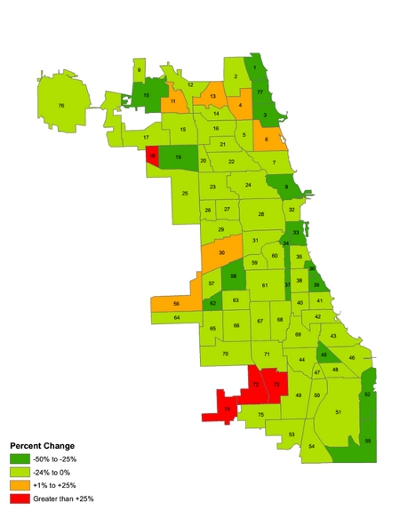

Finally, falls in crime and murder are unevenly distributed. While nearly every community in Chicago has experienced a decrease in violence since the mid-1990s, some communities saw greater declines than others. Figure 4 illustrates this point by mapping the changes in rates of violence crime from 2011 to 2013 by the city’s 77 community areas. More importantly, the difference in crime rates between the city’s lowest-crime communities and its highest-crime communities are rather dramatic. For example, the average annual homicide rate between 2000 and 2010 in Jefferson Park, located on the city’s Northwest side, was 3.1 per 100,000 residents. In stark contrast, West Garfield Park on the city’s Westside had a rate of 64 per 100,000. Inequalities such as these remind us that even though the city as a whole has come far over the past decades, a significant and palpable crime gap remains.

Figure 4 – Percentage Change in Violent Crime Rate in Chicago by Community Area (2011 to 2013 – Period from Jan 1 to Nov 30)

These historical trends offer mixed news. On the one hand, the city often portrayed as the murder capital of the nation is much safer than we are often led to believe. On the other hand, there is a persistent crime gap between low-crime and high-crime neighborhoods, with the most distressed communities not reaping the full benefits of Chicago’s crime decline.

Sadly, there is no reset button on January 1. The “first murder of the year” will be as painful for the family and community affected by it as one that occurs in the last week of December. However, a better understanding of the Chicago’s history and crime rates will help us make informed decisions about a way forward. Focusing on how to close the crime gap between low-crime and high-crime communities represents one of the most important next steps we can take.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/MoVMQi

_________________________________________

Andrew V. Papachristos – Yale University

Andrew V. Papachristos – Yale University

Andrew V. Papachristos is an Associate Professor of Sociology, Public Health, and Law at Yale University. His research focuses on social networks, neighborhoods, street gangs, and interpersonal violence.

Just to point out: the FBI doesn’t “name” any place the most violent city and certainly isn’t handing out the “murder capital” line. In fact, when you go to their web site they explicitly warn against ranking cities. They simply collect data and put it in one place; it is web sites and the media that come up with the distinction.

Andy, take another drink of the Kool Aid buddy. The stats are cooked. Sure we have less everything in the last three years. Ready? the powers that are giving you the stats are fudging. Guess what? we have less cars then in the sixties. Know why? Well! we no longer count Fords. Get it Andy. New math buddy.

@Bob Angone: You need a new antenna for your tinfoil hat…

Chicago violent areas are extremely dangerous places to be. Don’t sweep it under the rug there’s a problem in chicago that’s looming and unlike any of the other cities chicago gang culture is unlike anything you can imagine

Just a small amount of research into violent crime in Chicago reveals that Chicago at present is much less violent that it was in the Seventies and in the Nineties!

Looking this article and murder rates, he’s not sweeping anything under the rug. He’s exposing the truth. Chicago has been misrepresented. Just because we have certain problems that maybe worse than any other city, doesn’t mean we are the murder capital. There are far dangerous cities in the U.S. than Chicago.

People are judging the ENTIRE city, not purely the violent areas like you point out. That’s the point he’s making. Those dangerous areas don’t truly tell you about the city over all, just those areas or communities. When you look at them in comparison to the whole city, the city isn’t the worse, but is bad in parts. The gang issue is a problem, but even then that doesn’t mean we are the murder capital. In other words, people need to look at things in context or it’s entirety before dubbing entire culture, city, country, or group.

What’s just as dangerous as sweeping it under the rug is wrongfully dubbing an entire city, based on dangerous pockets within it.

In my own personal experience, I felt SAFE in Chicago because for the first 15 years of my life there and the few times I’ve been back to the city, I HAVENT BEEN SHOT just like I was about a year after moving here to Los Angeles where I now reside!!!!!!