The Iraq War Resolution of October 2002 was broadly supported in Congress, passing with bipartisan majorities in both chambers (296-133; 77-23), but the conflict rapidly became unpopular, especially with members of the Democratic Party. Drawing on data from the Iraq War, Douglas Kriner examines how members of Congress respond to casualties, both on the national level and within their constituencies. He argues that congressional feelings on a conflict should be of great concern to the president because members of Congress are highly effective at rallying their constituents to support a war.

The Iraq War Resolution of October 2002 was broadly supported in Congress, passing with bipartisan majorities in both chambers (296-133; 77-23), but the conflict rapidly became unpopular, especially with members of the Democratic Party. Drawing on data from the Iraq War, Douglas Kriner examines how members of Congress respond to casualties, both on the national level and within their constituencies. He argues that congressional feelings on a conflict should be of great concern to the president because members of Congress are highly effective at rallying their constituents to support a war.

President Obama stunned many Americans this past August when he announced that he would first go to Congress to seek its blessing for a military strike against the Syrian regime of Bashar Al-Assad for its use of chemical weapons. Since World War II, presidents have routinely invoked their authority as commander in chief to order American military strikes across the globe without first seeking congressional assent. At the same time, Congress has repeatedly shown itself unwilling to use the formal legislative tools at its disposal to curb military actions with which it disagrees. Why then, did Obama look to Congress? The President’s decision reminds us that even when Congress does not legislate, the public positions that its members take on a war may nonetheless be politically important. Presidents value public expressions of support and seek to avoid vocal criticism—the “sniping from the sidelines” alluded to by President Obama in his August 31 address—of their military policies.

Despite its political importance, we know surprisingly little about the factors driving congressional wartime position-taking. As the American experience in Vietnam plainly showed, the wartime positions of members of both parties can evolve significantly over time. Co-author Francis Shen and I argue that members of Congress respond to events as they unfold on the battlefield when deciding whether to publicly support or oppose the president and his policies. However, how members react to battlefield events is in large part conditional on their political partisanship.

Members of the opposition party are inherently more inclined to criticize the president’s conduct of a war than are his co-partisans on Capitol Hill. But even opposition members are wary that their positions may be seen as failing to support the troops in the field. For such members, setbacks on the battlefield, such as spikes in American casualties, raise important questions about the president’s policies and open windows of opportunity for public criticisms of the commander in chief.

By contrast, the president’s co-partisans stand to gain little from criticizing the administration, even in the wake of high casualties. Any effort to distance themselves from a costly war is likely to be undermined by an overall weakening of their party’s brand name. As a result, co-partisans are often reluctant to challenge their leader at the other end of Pennsylvania Avenue, even in the face of mounting battle deaths.

However, some members of the president’s party can eventually be persuaded to break publicly with the administration – and such same-party criticism receives considerable attention from the mass media. Local casualties from a member’s own constituency are important drivers of public war criticism for members of all partisan stripes. Even the president’s co-partisans respond to mounting casualties affecting their narrow geographic constituencies by becoming more vocal in their disapproval of the war and the president’s handling of it.

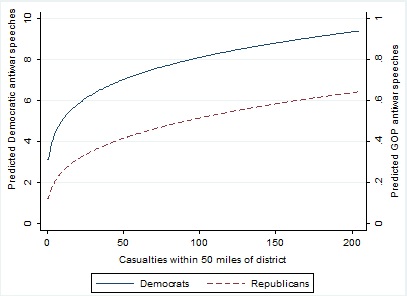

We test these hypotheses through an analysis of more than 7,500 speeches given on the House floor concerning the war in Iraq from 2003 through 2010. In the aggregate, we find unambiguous evidence that Democratic anti-war rhetoric increases when casualties rise and wanes when the casualty rate decreases. Republican criticism of the war, by contrast, was unrelated to casualty trends in the aggregate. However, as illustrated in the predicted values presented in Figure 1, both Democratic and Republican members responded to casualties sustained in their district by becoming more publicly critical of the war. To be sure, even Republicans representing districts that sustained high casualty levels were reticent to criticize the war. However, any public criticism from Republicans was amplified by a media eager to highlight even modest fissures in the GOP ranks.

Figure 1: District Casualties and War Criticism

But do the positions taken in Congress actually affect the American public’s willingness to back a war? With Congress’ approval rating mired in the teens and occasionally dipping even into the single digits, there are reasons for skepticism. Nevertheless, previous research suggests that when congressional elites of both parties support a war, the public rallies around it as well. By contrast, when elites divide over a conflict’s wisdom, the public follows suit. Moreover, as Richard Fenno observed forty years ago, while Americans routinely proclaim their distaste for Congress as an institution, most express considerable support for their local representative. Building on Fenno’s insight, we exploit the significant variation in congressional position-taking across the country to examine whether the positions taken by individual members of Congress regarding the Iraq War influenced the willingness of their constituents to support or oppose the conflict. Americans from districts represented by members who publicly and intensely criticized the Iraq War repeatedly were significantly more likely to judge the war a mistake and to oppose staying the course there than were Americans living in other districts represented by members who were less vocally critical of the war. In this way, members of Congress can raise the domestic political costs for the President to pursue his preferred military policy course by brining public pressure to bear on the administration, even when Congress as a whole finds itself unable to act legislatively to rein in a wayward commander in chief.

But do the positions taken in Congress actually affect the American public’s willingness to back a war? With Congress’ approval rating mired in the teens and occasionally dipping even into the single digits, there are reasons for skepticism. Nevertheless, previous research suggests that when congressional elites of both parties support a war, the public rallies around it as well. By contrast, when elites divide over a conflict’s wisdom, the public follows suit. Moreover, as Richard Fenno observed forty years ago, while Americans routinely proclaim their distaste for Congress as an institution, most express considerable support for their local representative. Building on Fenno’s insight, we exploit the significant variation in congressional position-taking across the country to examine whether the positions taken by individual members of Congress regarding the Iraq War influenced the willingness of their constituents to support or oppose the conflict. Americans from districts represented by members who publicly and intensely criticized the Iraq War repeatedly were significantly more likely to judge the war a mistake and to oppose staying the course there than were Americans living in other districts represented by members who were less vocally critical of the war. In this way, members of Congress can raise the domestic political costs for the President to pursue his preferred military policy course by brining public pressure to bear on the administration, even when Congress as a whole finds itself unable to act legislatively to rein in a wayward commander in chief.

This article is based on the paper “Responding to War on Capitol Hill: Battlefield Casualties, Congressional Response, and Public Support for the War in Iraq,” which appeared in the American Journal of Political Science.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/LTsPvt

_________________________________

Douglas Kriner – Boston University

Douglas Kriner – Boston University

Douglas Kriner is an Associate Professor of Political Science and the Director of Undergraduate Studies at Boston University. His research interests include American political institutions, separation of powers dynamics, and American military policymaking.