Although Congressmen are elected to represent their districts and states, they will occasionally defy majority opinion to support the rights of a minority group. Drawing on data from House Democrats that voted against the popular Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), Benjamin G. Bishin and Charles Anthony Smith determine that favorable district composition, membership in the Congressional Black Caucus, and competitive elections were associated with opposition to DOMA. They conclude that the difficulty of passing legislation to protect minority rights leaves the courts as the best option for such advancement.

Although Congressmen are elected to represent their districts and states, they will occasionally defy majority opinion to support the rights of a minority group. Drawing on data from House Democrats that voted against the popular Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), Benjamin G. Bishin and Charles Anthony Smith determine that favorable district composition, membership in the Congressional Black Caucus, and competitive elections were associated with opposition to DOMA. They conclude that the difficulty of passing legislation to protect minority rights leaves the courts as the best option for such advancement.

At the time the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) passed in the United States, a majority in every state and all but four congressional districts strongly opposed gay marriage. Support was the strongest in New York State, with 36% in favor, while nationally only 27% of Americans supported gay marriage. This widespread opposition provides an excellent opportunity to investigate the conditions under which legislators might ignore public opinion to support the rights of a minority group. In the Senate, all 14 members who bucked public opinion to vote against DOMA were Democrats and in the House, 66 of the 67 House members that voted against DOMA were Democrats. Three of those House Democrats were from districts that supported marriage equality. The only Republican to vote against the bill, Steve Gunderson (WI-3), had been outed as gay by a conservative Republican on the House floor during the debate.

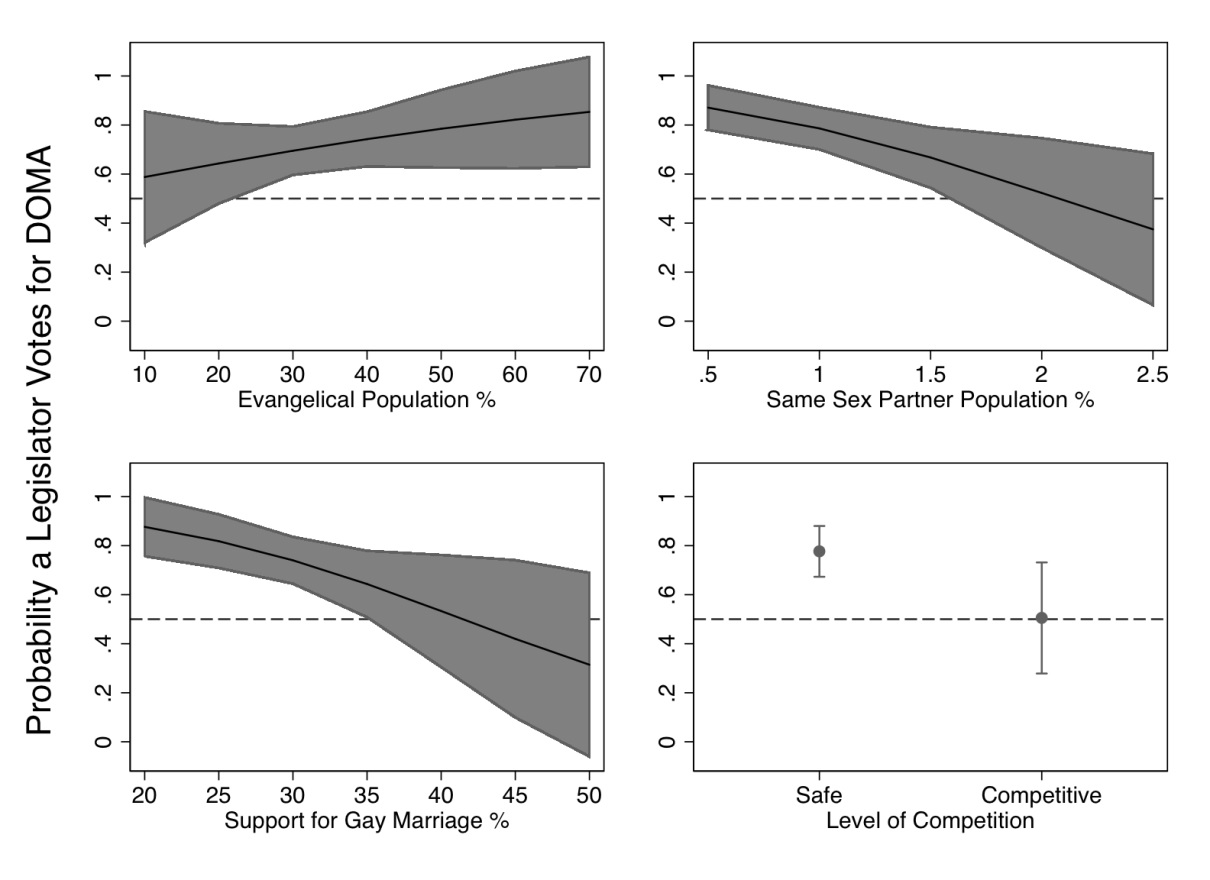

Because the Republicans were virtually unified, their votes provide us with little leverage, so we looked at the votes of House Democrats to understand when a legislator might defy public opinion. Specifically, we examined the relationship between House Democrats’ DOMA vote and measures of constituency support for gay marriage, the size of the district’s evangelical and gay populations and whether legislators faced a competitive challenge, as indicated by a victory margin of fewer than 10 points, in the 1994 election. Additional constituency characteristics we examined included the size of the black and Hispanic populations, the percentage of Democrats in the district and whether the legislator is a member of the congressional Black or Hispanic Caucus. As Figure 1 below shows, we found that public support for gay marriage, the size of the LGBT population, whether the legislator is a member of the Congressional Black Caucus, and the percent of the district that identifies as Democratic, were all significantly associated with opposition to DOMA. In fact, only the size of the black population in the district is associated with increased support for DOMA. Interestingly, we also found that that legislators from more competitive districts were less likely to support DOMA.

Figure 1 – Probability that House Democrats vote for DOMA and independent variables

Judging substantive significance by the likelihood that a particular factor might lead a legislator to change their vote, both public opinion and the size of the gay population have large influences on Democrats’ vote on DOMA. In contrast, Democrats appear less sensitive to the size of the Evangelical community. The bottom right panel indicates that while there are large differences in the behavior of legislators from safe versus competitive districts, Democrats from competitive districts are more likely to buck public opinion to oppose DOMA. This effect is so large, in fact, that when moving from a safe to a competitive district, legislators go from having about an 80% chance of supporting DOMA when safe to an almost even chance (51%) when competitive.

Judging substantive significance by the likelihood that a particular factor might lead a legislator to change their vote, both public opinion and the size of the gay population have large influences on Democrats’ vote on DOMA. In contrast, Democrats appear less sensitive to the size of the Evangelical community. The bottom right panel indicates that while there are large differences in the behavior of legislators from safe versus competitive districts, Democrats from competitive districts are more likely to buck public opinion to oppose DOMA. This effect is so large, in fact, that when moving from a safe to a competitive district, legislators go from having about an 80% chance of supporting DOMA when safe to an almost even chance (51%) when competitive.

At first glance, given the public’s historic opposition to gay marriage, the fact that public opinion performs so well might be positively viewed by advocates of minority rights. After all, the last decade has seen dramatic increases in public support for gay marriage. Our research suggests, however, that shifting public opinion alone is not likely to be sufficient to enact changes in this policy area given the intense opposition by religious conservatives and the relative ease with which legislation can be impeded. After all, there is no reason to expect that Republicans would not shirk majority district opinion to support their subconstituency and party positions just as many Democrats did on DOMA.

It is likely not enough, however, to simply elect large numbers of Democrats. While Democrats today are much more likely to support gay rights, some still vote against expanding such rights. Instead, when legislative action is required to enact or protect gay marriage, shifts in public opinion also must be accompanied by the election of large numbers of Democrats, since they are most likely to both to shirk opposing public opinion, and to support gay rights themselves, and their election necessarily displaces Republicans who seem more likely to oppose public opinion in order to take anti-gay positions.

The degree to which legislatures protect the rights of minorities also seems to partly depend on who holds power in them. While the election of Democrats alone is not enough to ensure gay rights, in cases like California, Vermont, and New Hampshire, where Democrats have large majorities, legislatures regularly consider and support bills advancing the rights of gays and lesbians. Consequently, the election of Democrats seems to be a necessary but insufficient prerequisite for progress. It is worth emphasizing, however, that Republican control is more likely to lead to the consideration and passage of anti-gay legislation, as in the US Congress, with DOMA. Of those Republican legislators who cast votes on the bill we examine in this paper, for instance, less than 0.5% (1/278) voted to support gay marriage.

Given these difficulties with using the legislature to protect minorities, in the short term, it appears that courts continue to offer the best venue for the advancement of rights.

This article is based on the paper “When Do Legislators Defy Popular Sovereignty? Testing Theories of Minority Representation using DOMA,” which was published in Political Research Quarterly 66(4): 794-803.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1jLpFVD

_________________________________

Benjamin G. Bishin– University of California, Riverside

Benjamin G. Bishin– University of California, Riverside

Benjamin G. Bishin is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the UC Riverside. His research interests include questions of democracy, representation, identity and ethnicity, public opinion and legislative politics. He is the author of Tyranny of the Minority The Subconstituency Politics Theory of Representation (Temple University Press 2009) and the recipient of the 2011 Bailey Award for the best paper on gay and lesbian politics for the paper “Gay Rights and Legislative Wrongs: Representation of Gays and Lesbians,” which he coauthored with Charles Anthony Smith.

Charles Anthony Smith- University of California, Irvine

Charles Anthony Smith- University of California, Irvine

Charles Anthony Smith is an Associate Professor of Political Science at UC Irvine. His research is grounded in the American judiciary and focuses on how institutions and the strategic interaction of political actors relate to the contestation over rights. He is the author of The Rise and Fall of War Crimes Trials from Charles I to Bush II (Cambridge University Press 2012) and the recipient of the 2011 Bailey Award for the best paper on gay and lesbian politics for the paper “Gay Rights and Legislative Wrongs: Representation of Gays and Lesbians,” which he coauthored with Benjamin G. Bishin.