Competing characterizations of the U.S. economy by President Obama and Mitt Romney during the 2012 presidential election help illustrate two important elements of election forecasting. First, the change in an economic indicator, relative to its level, better predicts the incumbent party’s share of the two-party vote. Second, presidential candidates make important campaign decisions, like whether to enter the race or what to talk about if they do, based on the state of the nation’s economy at the start of election year. Lynn Vavreck has explored the latter topic in The Message Matters: The Economy and Presidential Campaigns. Here, she suggests that adding a measure of campaign quality or effort can improve our predictions of election outcomes.

Competing characterizations of the U.S. economy by President Obama and Mitt Romney during the 2012 presidential election help illustrate two important elements of election forecasting. First, the change in an economic indicator, relative to its level, better predicts the incumbent party’s share of the two-party vote. Second, presidential candidates make important campaign decisions, like whether to enter the race or what to talk about if they do, based on the state of the nation’s economy at the start of election year. Lynn Vavreck has explored the latter topic in The Message Matters: The Economy and Presidential Campaigns. Here, she suggests that adding a measure of campaign quality or effort can improve our predictions of election outcomes.

This article is part of a collaboration with the PS: Political Science and Politics symposium on US Presidential Election Forecasting. Click here to read other posts in this series

As scholars, we have spilt gallons of ink debating and refining models that forecast election outcomes with little more than a cursory nod to the fact that these predictions are made by evaluating elections in which competing candidates typically wage hard-fought campaigns. In reality, our economic forecasting models tell us what to expect given the typical level and quality of campaigning in presidential races over the last several decades. Yet we rarely put a measure of campaign quality in forecasting models.

Just as variations in the state of the economy can shift forecasts, so too can variations in the level and quality of campaigning, but we know much less about how this translation works. There is almost no better pair of campaigns with which to illustrate the importance of variations in candidate behavior to predicting election outcomes than the campaigns run in 2012 by Barack Obama and Mitt Romney. A simple economic forecast done months before the election predicted an Obama victory by about 2.4 points (Sides and Vavreck 2013, p. 177-178). If we knew in April of 2012 that Mitt Romney would get the nomination and talk mainly about the fact that the economy was not growing fast enough, would we have more or less confidence in the 2.4-point victory the model delivered? Or is this information irrelevant to that prediction entirely? In The Message Matters (2009, p. 109), I explain why and demonstrate how this knowledge boosts our confidence in our estimate of the outcome. Here are the stylized facts.

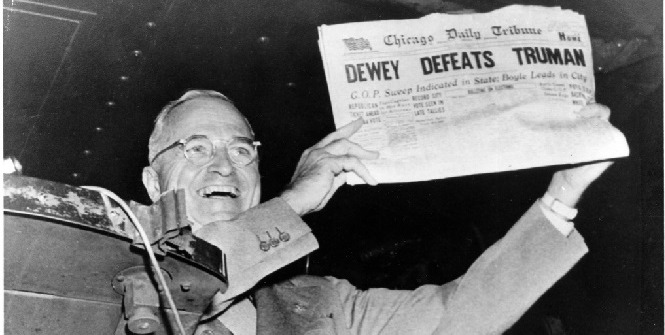

In nearly every presidential election since 1948 at least one candidate has focused his campaign predominantly on the state of the nation’s economy (see Vavreck 2009, p. 61). Typically, the candidate who focuses a campaign on the nation’s economy is the candidate predicted to win based on a simple economic forecast (of the last 16 candidates in this position, 11 of them did so). But sometimes candidates who are not predicted to win highlight the economy, too (George McGovern, Bob Dole, John McCain, and Mitt Romney). Clearly, candidates understand the powerful role that the state of the nation’s economy plays in American presidential elections and craft their messaging strategies in light of it.

The decision by Romney to focus his messaging on the economy increases our confidence in the economic model’s prediction because since 1948 no candidate predicted to lose based on the economy, who made the economy the central message of his campaign, has ever won. It was unlikely that Romney would be the first. To be clear, some candidates who were predicted to lose based on the economy who talked about things other than the economy were able to win these elections. So being disadvantaged alone is not enough to guarantee a loss.

Having said that, however, data on people’s perceptions of the nation’s economy and changes to it over the course of 2012 illustrate why Romney may have deemed this strategy a viable one. In December of 2011, according to YouGOV, only 20% of the population thought the economy had improved over the last year. The remainder split nearly evenly between thinking it got worse or stayed the same. Given this distribution of opinion it is not hard to see why Romney thought a campaign focused on Obama’s failure to turn the economy around could win him votes. The problem for Romney was the slippage between people’s perceptions of the economy and the actual economy.

In the last 60 years of presidential campaigns, all of the economically disadvantaged candidates who tried to reshape voters’ assessments of the economy lost their elections. Surely part of the explanation for this is that people’s opinions are hard to move, but perhaps a larger part of the story is the fact that election outcomes are more highly correlated with objective economic conditions than with people’s retrospective assessments of the economy – something that is counter-intuitive for most political analysts and difficult for candidates and strategists to believe. The data on this point, however, are clear. Since the American National Election Study started asking its traditional retrospective economic assessment question (1980), the percent of people who describe the economy as “getting better” over the last year is correlated with incumbent party vote share at .46. But, the percent saying the economy got better over the year correlates with the actual half-year growth rate at just .57. And here’s the critical piece of evidence: the objective change in GDP over the first half of the election year correlates with incumbent party vote share at .75.

Even if a candidate is successful at changing people’s minds about the state of the nation’s economy, it’s not clear the payoff is there.

Would knowing nine months before the election that Romney planned to center his campaign on the too-slow pace of the economic recovery have affected the forecasts of the 2012 election? Yes. Among economically disadvantaged candidates who tried to refocus the election off of the economy and on to something else, nearly a third went on to win. But among those who tried to reframe the objective economy to benefit their candidacies – none went on to win. The effect of the campaigns is “baked in” to our forecasting models, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try to systematize and appreciate how campaign effort and quality shape outcomes and therefore forecasts. With 2016 right around the corner, we have our work cut out for us.

This article is based on the paper ‘Want a Better Forecast? Measure the Campaign Not Just the Economy’ appearing in this month’s PS: Political Science and Politics symposium on US Presidential Election Forecasting. Click here to read other posts in this blog series.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1n6sIMD

_________________________________________

Lynn Vavreck – UCLA

Lynn Vavreck – UCLA

Lynn Vavreck is Professor of Political Science and Communication Studies at UCLA. She has published four books on presidential campaigns including The Message Matters: The Economy And Presidential Campaigns and The Gamble: Choice And Chance In The 2012 Presidential Election, portions of which she and John Sides wrote and released in real time during the 2012 election. She is the originator of the Cooperative Campaign Analysis Project and a contributing columnist to The Upshot at The New York Times.