The rise of social media, online campaigning and big data techniques has put a new spin on the traditional ‘ground game’ in political campaigns. Using data from the 2008 and 2012 presidential elections, Joshua Darr and Matthew Levendusky investigate why campaign field offices are located where they are, and whether or not they can make a difference in elections. They find that, through strategic placement, Obama’s field offices accounted for as much as 50 percent of his margin of victory in some states. They argue that in an era of billion dollar campaigns, field offices offer a cost effective way to mobilize voters and leave a legacy of local volunteers.

The rise of social media, online campaigning and big data techniques has put a new spin on the traditional ‘ground game’ in political campaigns. Using data from the 2008 and 2012 presidential elections, Joshua Darr and Matthew Levendusky investigate why campaign field offices are located where they are, and whether or not they can make a difference in elections. They find that, through strategic placement, Obama’s field offices accounted for as much as 50 percent of his margin of victory in some states. They argue that in an era of billion dollar campaigns, field offices offer a cost effective way to mobilize voters and leave a legacy of local volunteers.

American political campaigns now use many more methods for finding and contacting voters than at any point in American history. Much has been written on the roles of technology, big data, and social media in recent campaigns, but there has been a corresponding rise in old-fashioned campaign techniques—particularly establishing campaign field offices. Local field offices, strategically established in cities and towns across the country, translate this new information into actual voter contacts. At their most basic level, field offices serve as the point of contact between campaigns and ordinary voters. Campaigns send information on likely voter targets to field offices, which then dispatch their most effective messengers—local, well-trained volunteers—to target appeals to their chosen voters.

In recent research, we asked: where do campaigns choose to invest in field offices; and what are the effects (if any) of field offices on voter behavior? We find that Democrats and Republicans have differing field office allocation strategies and field offices increase turnout and a candidate’s vote share in areas where they are located.

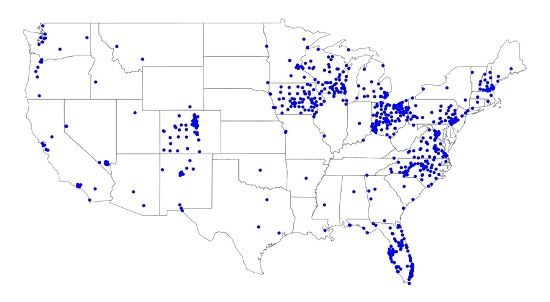

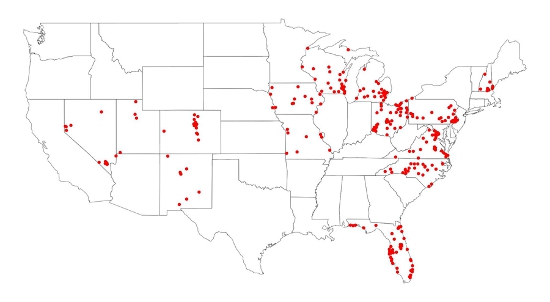

The places in which campaigns choose to invest can shed light on their perceived path to victory. Do campaigns choose to “run up the score” in friendly “core” areas, try to win contested “swing” areas, or make inroads into their opponent’s territory? We use data from the 2012 presidential election to address these questions. Figures 1 and 2 depict where campaigns chose to open field offices in 2012.

Figure 1: Obama field offices, 2012

Figure 2: Romney field offices, 2012

Unsurprisingly, most (though not all) field offices were located in battleground states. Both the Barack Obama and Mitt Romney campaigns invested more heavily in their core counties, trying to turn out their voters where they were most plentiful. In the case of swing counties, however, Obama and Romney’s strategies diverged. Romney avoided Democratic areas almost completely, while Obama invested roughly equally in swing and Republican core counties. When Obama opened an office in a swing county, so did Romney. But a Romney office did not necessarily prompt Obama to open an office there. These strategic differences could be due to demographic and geographic factors—Democratic voters tend to be more highly concentrated in large cities—but they might reflect the well-publicized data (and financial) disparity between the campaigns. If Obama’s campaign was better at using data to find the few Democrats in largely Republican counties, they may have been more willing to invest in those areas, though more work will be needed to definitively establish this point.

Having found that campaigns establish field offices strategically, we turned to the question of whether they receive any return on their investment. Using Democratic field office placement data for 2004, 2008, and 2012, we examine the effects of field office placement on turnout and aggregate vote choice. Sparing the details (though those interested can consult our paper), we find a small but significant effect of field offices on both turnout and vote choice.

On average, a field office in a county increases turnout by 0.4%, and Democratic vote share by approximately 1%; we also find that field offices are more effective in battleground states than in safe states. These results demonstrate that the activities centered in field offices turn out partisan voters, and they do so where they are expected to be most active—in battleground states. Given the relative stability of county-level vote shares (which have an average standard deviation of 3% in the years measured), a 1% shift in the desired direction in county-level vote share is a meaningful effect of campaign investment.

When we place these results in their geographic context, their influence becomes even more apparent. In 2008, Obama’s field offices netted him an average of 425 additional voters per county and 275,000 additional voters nationally. Of these, 200,000 were in battleground states—providing 7% of his total margin of victory in these critical states. We calculated that field offices accounted for 50% of Obama’s margin of victory in Indiana, and Obama would likely have lost North Carolina but for his network of field offices and their subsequent voter mobilization.

We also looked at the relative cost of field office operations. Operating a field office requires paying rent and the salary of the local organizer, as well as obtaining computers for data entry and providing food for volunteers. These costs add up: field offices cost an average of $21,000 per office, for a cost-per-additional-vote total of nearly $50/vote. This cost-per-vote estimate is significantly more expensive than those in previous studies of the efficiency of canvassing, but we think it more accurately reflects the real costs of implementing in-person voter contact in campaigns. Previous estimates assumed volunteer canvassers with no infrastructure, but our study points out that for those canvassers to be effective, they need the field office to coordinate their efforts. Further, in the era of billion-dollar political campaigns, these expenses are minor: field operations budgets pale in comparison to advertisements. In-person mobilization appears to be one of the more effective expenditures campaigns can make with their limited resources.

American presidential elections are national battles waged in increasingly local areas. There is more money to spend on implementing the lessons gained through better data on voter contact operations. As the continued lobbying operation of the Obama campaign (i.e., “Organizing for America”) demonstrates, this sort of participation can even endure between election cycles. Though technological change and increased money are often decried as removing people from politics, campaigns can also use these forces to increase volunteerism, political participation, and voter turnout. Face-to-face, community-centered voter contact increases campaigns’ vote share in targeted areas and leaves a local legacy of volunteers with politically valuable skills.

This article is based on the paper ‘Relying on the Ground Game: The Placement and Effect of Campaign Field Offices’, in American Politics Research.

Featured image: Steve Rhodes (Creative Commons BY NC)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1qwoPDm

_________________________________

Joshua Darr – University of Pennsylvania

Joshua Darr – University of Pennsylvania

Joshua Darr is a Ph.D. candidate in Political Science at the University of Pennsylvania. His research focuses on American politics and political communication.

_

Matthew Levendusky – University of Pennsylvania

Matthew Levendusky – University of Pennsylvania

Matthew Levendusky is currently an associate professor of political science at the University of Pennsylvania. His research focuses on understanding how institutions and elites influence the political behavior of ordinary citizens. This broad question is taken up in studies of mass polarization, voter cue taking, the impact of partisan media on ordinary voters, and a variety of other substantive questions.