This month has seen an unfolding scandal over ‘secret’ Veterans Affairs lists for veterans waiting to see doctors, and now many Republicans and Democrats are calling for the resignation of Secretary Eric Shinseki. Barbara Romzek writes that the scandal stems from the burdens placed on Veterans Affairs employees who gamed the waiting list system in order to please their own bosses. She argues that the scandal reflects the tangled web of accountability placed on Veterans Administration at the same time as it has experienced a massive increase in demand for healthcare from veterans. While firing Shinseki and others may give the perception of ‘doing something’, she writes, it will do little to solve the underlying problems.

This month has seen an unfolding scandal over ‘secret’ Veterans Affairs lists for veterans waiting to see doctors, and now many Republicans and Democrats are calling for the resignation of Secretary Eric Shinseki. Barbara Romzek writes that the scandal stems from the burdens placed on Veterans Affairs employees who gamed the waiting list system in order to please their own bosses. She argues that the scandal reflects the tangled web of accountability placed on Veterans Administration at the same time as it has experienced a massive increase in demand for healthcare from veterans. While firing Shinseki and others may give the perception of ‘doing something’, she writes, it will do little to solve the underlying problems.

The recent revelations that Veterans Affairs (VA) workers have gamed their medical appointment schedules to hide the long delays veterans faced before seeing doctors should concern every American. There have also been consistent complaints about the hurdles vets must overcome to establish eligibility. Veterans have made supreme sacrifices in defense of their country, and they deserve the best care our nation can offer. How is it possible that in a political system that proclaims love and honor for military service, we find such problems?

The quick answer is a lack of accountability. Despite the deserved outrage, it is more instructive to view the scandal at the VA as a reflection of the complicated accountability picture in the U.S. government. Americans have a fundamental distrust of government. Our thinking goes like this: if some accountability is good, then more must be better. The result of such thinking is a tangled web of accountability within which most American government employees operate.

This tangled web is reflected in government agencies and employees working under several overlapping accountability mechanisms to hold them answerable for their performance. Government agencies and their employees are expected to be accountable to numerous groups in different ways at the same time. Under normal circumstances this is a manageable process because typically agencies and individuals focus on expectations from one or two primary sources of authority. In times of crisis or scandal, agencies and individuals face calls for accountability under each of the varied standards of accountability.

In the VA’s case, its short list of key sources to which it and its employees are accountable includes the president, the Congress, the VA’s top leadership, veterans, and the general public. These separate sources each typically have different expectations for the agency and its employees based on where they are located in the VA service delivery orbit. As a result the VA and its employees typically face competing and conflicting performance expectations and cross-pressures of accountability. The situation allows individuals to work to meet some legitimate expectations for performance but fail to meet another group’s expectations.

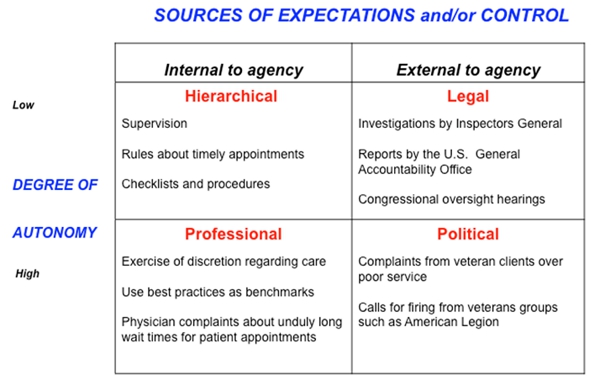

Employees of the VA typically are accountable through hierarchical standards (reporting to supervisors: Secretary Eric Shinseki, and by extension, President Obama) and professional standards of best practice, which involves employees using their discretion to provide the services best suited to the needs of veterans. When things went wrong, as they did in the VA, additional strands of the web of accountability (shown in Figure 1) are activated. These are reflected in congressional hearings, investigations by inspectors general, and reviews by other external agencies such as the Government Accountability Office, as well as calls for firing those responsible from veterans’ groups external to the agency, such as the American Legion.

This situation results in the wide ranging calls for accountability and proposed strategies that we hear from different legitimate sources – the president, Congress, inspectors general, physicians within the VA, and veterans groups. Each of these sources brings a different perspective, different expectations, and different remedies for ensuring that the situation for veterans is remedied.

Figure 1 – Formal Accountability in Veterans Affairs

Adapted from Barbara S. Romzek and Melvin Dubnick, 1987, Public Administration Review, “Accountability in the Public Sector,” 47: 227-238.

The VA case illustrates how overburdened government workers developed strategies to follow the rules but failed to meet the needs of their clients. The VA’s employees are under pressure to serve several masters— agency leadership, veterans, inspectors general, the president, and Congress, to name the short list. Because they were overburdened, VA employees played within the bureaucratic rules to please their bosses at the expense of their veteran clients. They did this by playing with appointment schedules. They gamed the system.

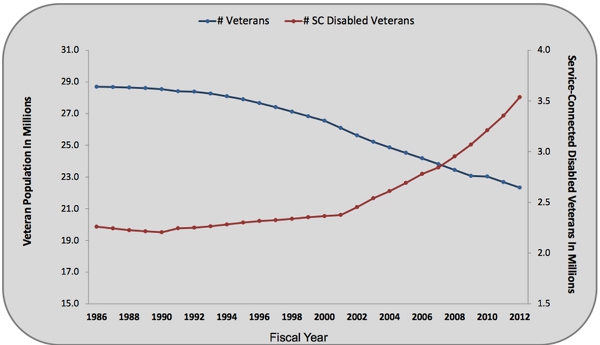

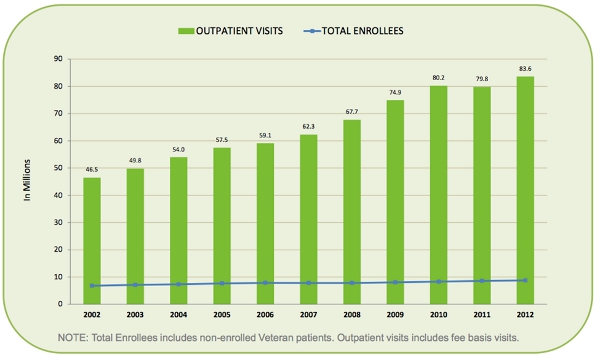

The mission of the VA is a challenging one. For over a decade, the VA has operated in an environment of increasing demand to provide service to its veteran clients. The VA is a sprawling bureaucracy. According to The New York Times, it treats 6.5 million people a year at 151 hospitals and 820 outpatient clinics, with more than 18,000 doctors and an annual budget of more than $57 billion. While the total number of veterans is declining, the number of veterans with a service connected disability has increased by over 1 million since 2000, according to the National Center of Veterans Analysis and Statistics (Figure 2). Even though the number of veteran enrollees has been relatively stable since 2002, the number of outpatient visits has nearly doubled (Figure 3). Overall, the VA has faced a 45% increase in demand for outpatient medical appointments.

Figure 2 – Veterans with a service-connected disability

Source: Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of the Assistant Deputy Under Secretary for Health for Policy and Planning. Prepared by the National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics.

Figure 3 – Trends in healthcare enrollees and outpatient visits

Source: Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of the Assistant Deputy Under Secretary for Health for Policy and Planning. Prepared by the National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics.

The time-honored response to such scandals is to “fire the scoundrels.” While there may be sufficient malfeasance to warrant firings, the problem facing the VA won’t easily be solved by dismissing one or many VA employees and bringing in new leadership to the existing system. Members of Congress and veterans groups calling for Gen. Erik Shinseki’s ouster are seeking a scapegoat. Such action gives the perception of doing something to solve the problem. Such a strategy may, in the short term, mollify a dissatisfied public. Doing so would merely be putting a band-aid over the complex accountability cross-pressures at work in this situation. It’s important to note that the barriers to quickly firing responsible employees within the VA lay in that same tangled web of accountability. The civil service system that protects public employees from firing without due process is an accountability mechanism put in place to prohibit undue political influence on nonpartisan civil servants.

The American political system with its checks and balances and complicated, tangled web of accountability is not an elegant system. This cacophony of calls for accountability at the VA is typical for the American political system, and the uproar and outrage expressed by these failures of accountability are healthy signs. Admittedly our tangled web of accountability may appear inefficient; it is. It takes time to identify responsible parties and appropriate actions. In the U.S., we have come to accept these inefficient processes of accountability as the price we pay for our democracy.

Americans want their government to be responsive to veterans and respectful of their service. And Americans are right to demand that the VA follow established procedures to ensure access and fairness. If the policy is for a veteran to have access to an appointment within two weeks of requesting one, then veterans have a right to see a doctor or nurse within two weeks.

There have been failures of accountability on the part of the VA and veterans have suffered. The VA and its employees are being brought to task for its shortcomings and there are likely warranted changes in procedures and personnel. The VA’s inspector general is working with federal prosecutors to determine whether criminal violations have occurred. Some VA employees have already been placed on administrative leave, an early step toward removal if the investigations demonstrate malfeasance. If serving our nation’s veterans is the real objective, diagnosing the agency’s problems and how to fix them are top political and management priorities. Veterans deserve no less.

It is also important to hold responsible those institutions that are tasked with keeping the VA accountable— the president and Congress, and the public. Americans need to hold the president and Congress accountable for their stewardship roles to ensure that the VA provides veterans with high-quality care. For the American public, accountability time comes at election time. Will the public remember veterans at election time? Time will tell if the voting public holds elected officials accountable at the polls for the severity of the problems at the VA.

Featured image credit: Secretary Shinseki, By DoD photo by Erin A. Kirk-Cuomo. (Released) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1pnuuu9

_________________________________________

Barbara Romzek – American University

Barbara Romzek – American University

Barbara Romzek is dean of the School of Public Affairs at American University; she received her Ph.D. in government from the University of Texas at Austin. Dr. Barbara Romzek is internationally recognized for her expertise in the area of public management and accountability with emphases on government reform, contracting, and network service delivery. Her research has encompassed complex work settings, including NASA, Congress, and the Air Force, as well as state agencies, local governments, and nonprofit agencies. Dr. Romzek, a Fellow of the National Academy of Public Administration, has received research awards from the American Society for Public Administration and the American Political Science Association. She currently serves on the Executive Council of the National Association of Schools of Public Affairs and Administration.