Even before the onset of the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, cities had become increasingly concerned about how to deal with their growing homelessness problem. In recent years, the anti-homelessness policies of the police have begun to lose favor, with a greater emphasis given to ‘homeless diversion programs’ that place homeless people into counselling and other rehabilitation services. In new research that concentrates on Los Angeles’ ‘Skid Row’ district, Forrest Stuart argues that such programs actually increase harm to homeless people by widening the criminal justice system to non-criminal behavior. He writes that officers view the use of arrests and citations as a viable way of channelling the homeless into rehabilitative social services, but that this causes homeless individuals to pull even further into the shadows of society.

Even before the onset of the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, cities had become increasingly concerned about how to deal with their growing homelessness problem. In recent years, the anti-homelessness policies of the police have begun to lose favor, with a greater emphasis given to ‘homeless diversion programs’ that place homeless people into counselling and other rehabilitation services. In new research that concentrates on Los Angeles’ ‘Skid Row’ district, Forrest Stuart argues that such programs actually increase harm to homeless people by widening the criminal justice system to non-criminal behavior. He writes that officers view the use of arrests and citations as a viable way of channelling the homeless into rehabilitative social services, but that this causes homeless individuals to pull even further into the shadows of society.

The last three decades have witnessed a backlash against homeless people. Beginning in the early 1990s, cities across America and the globe have adopted “zero-tolerance” police policies that aggressively criminalize the activities commonly associated with extreme poverty, including panhandling, loitering, and sitting on the sidewalk. Since that time, citation and arrest rates have soared to historic levels and homeless individuals now make up one sixth of the inmates currently sitting in US jails. This kind of repeated police contact has been shown to compound chronic homelessness by creating significant obstacles to finding stable employment, securing affordable housing, receiving adequate health care, and maintaining vital ties with family and friends.

In recent years, there have been signs that the anti-homeless policies of the police may be losing steam. Responding to public backlash and overcrowding in jails, many municipalities have partnered with non-profit, religious, and voluntary social service providers to create “homeless diversion programs” that channel arrestees into counseling, drug rehabilitation, and employment training in lieu of incarceration. On first glance, these public-private partnerships appear to be a major step in reducing the negative impacts of aggressive law enforcement policies on the down-and-out. For policy-makers and the public alike, they seem to represent a move toward a more compassionate approach to homelessness.

Initial appearances can be deceiving, however. Public policies that seem beneficial “on the books” sometimes produce unexpected and contradictory effects when applied “on the ground.” This is particularly true of policing policies because police officers possess significant discretion while on patrol – they ultimately decide how, why, and when official policies are implemented. This means that any assessment of police partnerships and homeless diversion programs needs to investigate how these policies play out in officers’ daily patrol practices.

In my recent research, I spent five years observing and interviewing officers who patrol Los Angeles’ Skid Row district. Long held as the “homeless capital of America,” LA’s Skid Row is the site of one of the most aggressive zero-tolerance policies in the US. It is also home to one of the country’s strongest partnerships between police and social service organizations. In one of the flagship diversion initiatives, aptly titled the Streets or Services (SOS) program, the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) gives homeless arrestees the option to forgo jail time if they agree to enroll in a 21-day recovery program at a participating homeless shelter or rescue mission. A similar program, called Homeless Alternative to Living on the Streets (HALO), allows those who have received citations the option to waive their fines by enrolling in rehabilitation programs.

In one of my recent articles, I compare the patrol behaviors of today’s Skid Row officers against patrol behaviors prior to the development of the LAPD’s partnership. The comparison yields startling evidence that public-private partnerships and their resulting diversion programs may serve to exacerbate chronic homelessness to an even greater extent. They do so by legitimating an elevated level of police aggressiveness that widens the net of the criminal justice system over additional and often non-criminal behaviors and individuals. Contrary to initial expectations, I find that the harm to homeless people has actually increased, though not in spite of compassion, but because of it.

One of the most immediate impacts of the partnership and its diversion programs is that it has changed the manner in which officers perceive the underlying function of citations and arrests. Rather than view them primarily as a punishment for illegal behavior, officers have come to envision citations and arrests as a viable form of “intake” into rehabilitative social services. When deciding who to cite or arrest, officers do not necessarily base their decisions on an individual’s technical guilt, but rather on their perceived need of services. This means that homeless individuals – particularly if they are female, mentally ill, and/or disabled – are singled out for citation and arrest at a higher rate than many others.

Embracing the “tough love” logic of diversion programs, officers also use their police powers to funnel homeless people into partnering organizations in more indirect ways. Specifically, officers use the threat of citation and arrest to make streets and sidewalks unwelcoming. As one officer described, “This shouldn’t be a vacation down here for people. To an extent you could say a big part of our job is to make this place as inhospitable as possible so that people finally hit rock bottom and get themselves into a mission.” Beyond disallowing homeless individuals from ever sitting down to rest, this logic prompts officers to prohibit churches, charities, and other philanthropic groups from handing out donations along the streets. According to officers, eliminating the availability of food and other resources is a technique for literally starving homeless people into approved rehabilitation programs. As one officer reported, “Everyone needs to eat, right? … [W]e’re all going to go where we can get food. It’s survival, plain and simple. In reality, it’s all about figuring out new ways to get people into the system.” In collaboration with their social service partners, the LAPD is currently sponsoring a proposed municipal ordinance that seeks to make philanthropic street donations a misdemeanor offense.

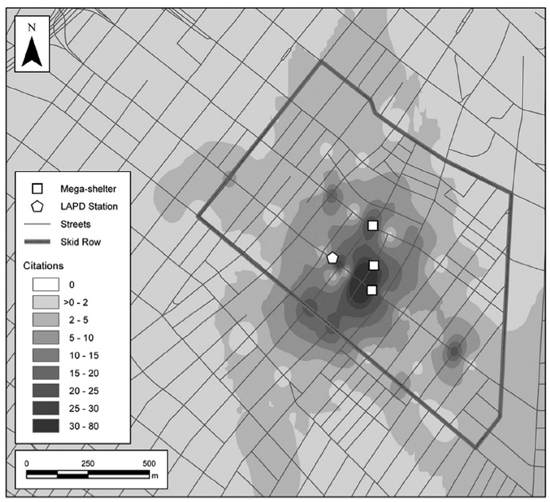

This new logic can be further seen in the spatial distribution of citations in and around Skid Row. Figure 1 shows the geographical locations of 751 citations that were brought to a free legal clinic operated by the Los Angeles Community Action Network – a grassroots civil rights and housing organization – over the course of two years. An overwhelming majority of these citations were issued along the sidewalks adjacent to partner organizations and diversion programs. As one officer explained, these citations serve as “one last nudge for [homeless people] to start getting their life back together.” In effect, officers are punishing those individuals who venture too closely to partner organizations without entering their doors.

Figure 1 – Citations issued in Skid Row and adjacent downtown, January 2010 through December 2011 (n = 741).

Despite being driven by sympathetic intentions, these new patrol practices entail major violations of homeless people’s constitutional rights. By replacing guilt with need as a primary criterion for legal punishments, the LAPD’s organizational partnership and the resulting diversion programs serve to amplify homeless people’s detrimental entanglements with the criminal justice system while leaving many others who commit more serious crimes (sometimes against homeless people) free to roam the streets. In observations and interviews with Skid Row’s homeless population, I find that this new use of police resources significantly intensifies homeless people’s fear not only of criminal victimization, but also of the police officers who are otherwise responsible for their physical protection. This increased insecurity causes our cities’ most vulnerable citizens to pull even further into the shadows, which entrenches them even more deeply in life on the streets.

These findings indicate that homeless diversion programs are far from the magic bullet that many assume. In fact, they may actually exacerbate chronic homelessness in unintended ways. This research also draws attention to the perils of enlisting the police to carry out social welfare tasks. Equipped primarily with handcuffs, handguns, and the coercive power of the law, police officers make poor social workers. Solving chronic homelessness instead requires public policies that re-invest in the social safety net and allow the police to return their attention to serious crimes.

This article is based on the paper ‘From ’Rabble Management’ to ’Recovery Management’: Policing Homelessness in Marginal Urban Space’ in Urban Studies.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1nZxaLU

_________________________________

Forrest Stuart – University of Chicago

Forrest Stuart – University of Chicago

Forrest Stuart is Assistant Professor of Sociology and the College at the University of Chicago. His research investigates the impacts of policing and criminal justice on the lives of the urban poor. His current book project His current book project, titled Policing Rock Bottom (University of Chicago Press), is an ethnographic examination of zero-tolerance policing in Los Angeles’ Skid Row district.