In recent years, it has become increasingly apparent that citizens are not represented equally by their elected officials in Congress and in statehouses across the United States, and that wealthier individuals, represented by lobbyists, are more successful in having their preferences translated into policy. In new research, Patrick Flavin examines the role of lobbying regulations on political representation. He finds that as the number of lobbying restrictions in a state increases, the greater the level of political equality. He argues that those seeking to promote greater political equality in the United States should consider strict laws that regulate the conduct of professional lobbyists to ensure that citizens’ opinions receive more equal consideration when elected officials make policy decisions.

In recent years, it has become increasingly apparent that citizens are not represented equally by their elected officials in Congress and in statehouses across the United States, and that wealthier individuals, represented by lobbyists, are more successful in having their preferences translated into policy. In new research, Patrick Flavin examines the role of lobbying regulations on political representation. He finds that as the number of lobbying restrictions in a state increases, the greater the level of political equality. He argues that those seeking to promote greater political equality in the United States should consider strict laws that regulate the conduct of professional lobbyists to ensure that citizens’ opinions receive more equal consideration when elected officials make policy decisions.

There is growing concern among social scientists, policymakers, and the general public about unequal political influence and its consequences for economic inequality in the United States. One common explanation for why affluent citizens tend to be more successful at getting their preferences translated into policy is that industries that tend to share their opinions (finance, real estate, etc.) are well represented among professional lobbyists in Washington and statehouses across the nation. In contrast, disadvantaged citizens do not enjoy the same level of representation among professional lobbyists, and correspondingly exert less influence over the policy decisions made by elected officials. In response to these perceived inequities, laws that regulate the registration and conduct of professional lobbyists have been one attempt to lessen the influence of wealthy interests and ensure that citizens’ opinions receive more equal consideration when elected officials make important policy decisions.

Are lobbying regulations actually effective at enhancing the equality of political representation? This question is difficult to answer at the federal level because one uniform set of laws regulates professional lobbyists in Washington and changes in those laws that occur over time are correlated with many other changes in the political system. By comparison, the fifty states vary dramatically in terms of how much, or little, they regulate the registration and conduct of professional lobbyists. For example, some states have few regulations on lobbying activities while other states have enacted strict requirements for lobbying disclosure, rules governing when lobbyists can meet with legislators, and limits or outright bans on the gifts lobbyists can give to elected officials.

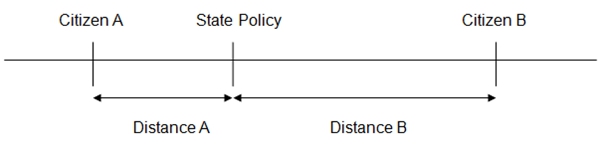

Despite the important implications for the quality of American democracy, no study to date has evaluated whether stricter lobbying regulations correspond to more egalitarian patterns of political representation. My research uses the variation across the fifty American states to examine the relationship between lobbying regulations and the equality of political representation. I uncover evidence that stricter regulations are associated with greater political equality. I begin by using public opinion survey data from the 2000, 2004, and 2008 National Annenberg Election Surveys to measure the “distance” between citizens’ political ideology and the general ideological tone of public policies in the state they live in. To accomplish this task, I use various statistical methods to place citizens’ ideologies and state policies on the same scale and then measure the distance between them. As an illustration, Figure 1 compares two hypothetical citizens, Citizen A and Citizen B, who both live in the same state. When the two citizens’ political ideologies are placed on the same scale as state policy, there is less ideological distance between Citizen A and state policy as compared to Citizen B and state policy. Under this conceptualization of policy representation, Citizen A is better represented than Citizen B.

Figure 1 – Ideological Distance between Opinion and Policy

Note: Using a proximity measure of political representation, Citizen A is better represented than Citizen B because the ideological distance between her opinion and state policy is smaller.

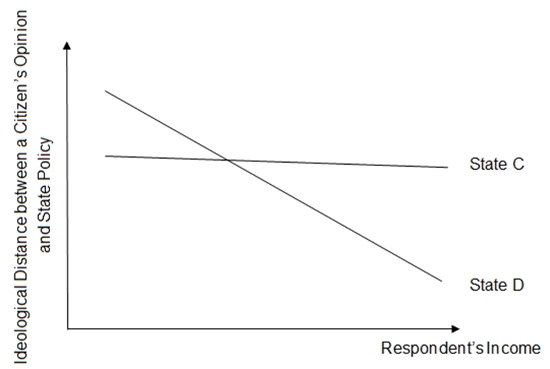

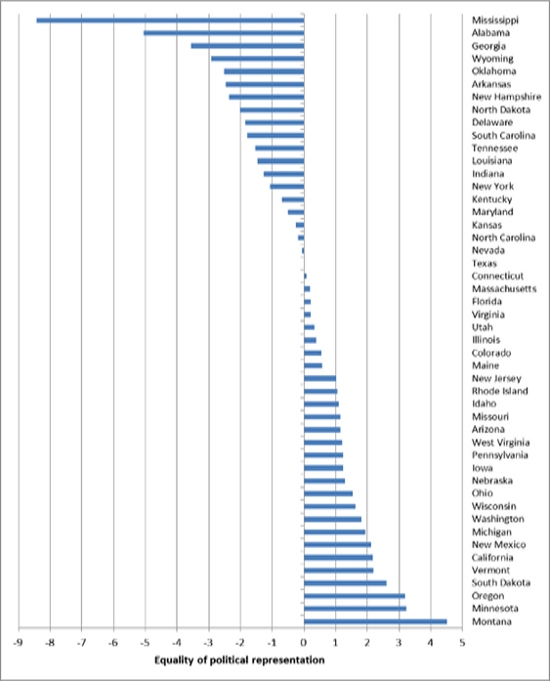

I then evaluate whether there is a systematic relationship between citizens’ incomes and the ideological distance between their opinion and state policy and find that nationwide as incomes increase, ideological distance decreases (i.e. wealthier citizens are better represented by government policies than poor citizens). Using this same logic, I examine the relationship between income and representation within each state. For example, consider the two hypothetical states presented in Figure 2. The relationship between income and distance is rather weak in State C, indicating that citizens’ opinions are weighted roughly equally regardless of their income. In contrast, the slope of the relationship between income and ideological distance is quite steeply negative for State D, indicating that there is a strong degree of political inequality in state policymaking. After running this analysis for each state, I am then able to rank the states by how politically equal they are. Figure 3 displays the ranking of the states from most equal to most unequal.

Figure 2- Relationship between Income and Ideological Distance, by State

Note: State C has more equal political representation than State D because the relationship between income and opinion-policy distance is weaker in State C compared to State D.

Figure 3 – Ranking the States by the Equality of Political Representation

Note: Equality values are factor scores from combining six coefficients for state specific regressions. Larger positive values indicate greater political equality (i.e. a weaker relationship between income and ideological proximity).

I then investigate if states that more strictly regulate the activities of professional lobbyists tend to have more egalitarian patterns of political representation. To do this, I use an additive index created by Adam Newmark at Appalachian State University that catalogues the number of different groups required to register as lobbyists, the frequency of reporting requirements, the types of activities that are prohibited, and disclosure requirements. Using regression analysis, I find that as the number of lobbying restrictions increases so does the equality of political representation and that the real world impact on political equality is larger than the effect of having more competitive elections or having fewer for-profit interest groups in a state (two common predictors of the equality of political representation). This result likely arises because tighter restrictions on registration, disclosure, and gift giving lessen the extent to which lobbyists have access to state policymakers and, by extension, attenuate the political influence of organized interests who tend to over-represent the opinions of wealthier citizens.

In light of these findings, those seeking to promote greater political equality in the United States should consider strict laws that regulate the conduct of professional lobbyists as one important tool for ensuring that citizens’ opinions receive more equal consideration when elected officials make policy decisions.

This article is based on the paper ‘Lobbying Regulations and Political Equality in the American States’, in American Politics Research.

Featured image credit: Danny Huizinga (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1wxngIn

_________________________________

Patrick Flavin – Baylor University

Patrick Flavin – Baylor University

Patrick Flavin is an assistant professor in the Department of Political Science at Baylor University. His research and teaching interests include political inequality, the impact of politics and public policies on citizens’ quality of life, U.S. state politics, political behavior, and research methods.

1 Comments