With the rise in prominence and influence of conservative politicians such as Senators Ted Cruz and Rand Paul in recent years, the role of the Tea Party in U.S. politics has become more and more important. In new research, Caitlin E. Jewitt and Sarah A. Treul examine how the presence of a Tea Party candidate – a divisive election – affects general election results compared to elections that are simply competitive. They find that competitive primaries increase turnout rates, but do little for a party’s election result. They also find that while the presence of a Tea Party candidate in the general election means that the Republican Party performs 1.7 percent better than expected, when there had been a competitive primary, there is no additional effect.

With the rise in prominence and influence of conservative politicians such as Senators Ted Cruz and Rand Paul in recent years, the role of the Tea Party in U.S. politics has become more and more important. In new research, Caitlin E. Jewitt and Sarah A. Treul examine how the presence of a Tea Party candidate – a divisive election – affects general election results compared to elections that are simply competitive. They find that competitive primaries increase turnout rates, but do little for a party’s election result. They also find that while the presence of a Tea Party candidate in the general election means that the Republican Party performs 1.7 percent better than expected, when there had been a competitive primary, there is no additional effect.

In the 2010 midterm election, the Republican Party had its best showing since 1946, gaining 63 seats in the House of Representatives, resulting in a GOP majority of 242 to 193. The Republican Party’s success in the general election may have been fueled, in part, by the higher than normal turnout in the Republican primaries. There is little dispute that the Tea Party increased the number of competitive Republican congressional primaries in 2010, but what is less known is how these competitive primaries influenced the general election results. In new research, we find that competitive primaries increase turnout in general elections, though they may not be the best way for a party to secure an electoral advantage.

Previous research is conflicted about the influence of competitive primaries on general elections, with some contending that high turnout in the primaries may create excitement, interest, and knowledge that carries over into the November ballot. Other research suggests that competitive congressional primaries tend to hurt the eventual nominee in the general election because voters are turned off by intraparty conflict or are emotionally attached to an unsuccessful primary candidate and are unwilling to shift their support to the party nominee.

These conflicting results leave us puzzled over the effect of competitive primaries on congressional general election outcomes, especially with the rise of the Tea Party. Since the Tea Party helped make many primaries competitive and signaled a division within the Republican Party, we looked at the 2010 congressional election to determine the relationship between competitive primaries and general election outcomes.

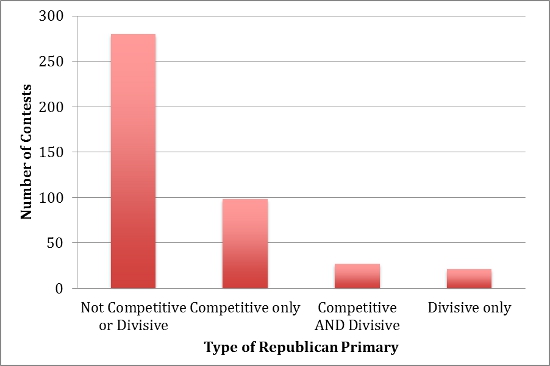

We contend that both competitiveness and divisiveness have individual and distinct effects and should not be conflated. In most political science research, divisiveness and competitiveness are treated as synonymous concepts, with a divisive primary being measured by the closeness of the results. Essentially, most previous work has measured competitiveness and called it divisiveness. We attempt to disentangle these two concepts. We define competitiveness as the closeness of the race, measured by whether the margin of victory between the primary winner and the second place candidate was less than 20 percent. We establish a divisive contest as those races where a Tea Party candidate was on the ballot because, in 2010, the Tea Party signified a serious rift in the typically cohesive Republican Party over the role of the government and the necessary level of fiscal conservatism. Figure 1 shows the number of 2010 Republican congressional primaries that we classified as divisive, competitive, or both competitive and divisive

Figure 1 – Competitiveness and Divisiveness in the 2010 Congressional Republican Primaries

Through a series of empirical models, we examine the effect of competitive primaries and divisiveness first on turnout in the general election and then on the Republican Party’s success in the 2010 general election.

First, we find that competitive Republican and Democratic primaries increased turnout in the 2010 general election. A district that held a competitive Republican primary had, on average, a turnout rate in the general election that was about 0.8 percent higher than a district that did not experience a competitive Republican primary. Districts where there were competitive Democratic primaries resulted in turnout rates that were, on average, 1.35 percent higher than districts where the Democratic primaries were uncompetitive. Given that turnout in congressional elections in midterm years is relatively low, this increase is considerable.

Second, we find no evidence of a relationship between a competitive Republican primary and the Republican Party doing better than expected in the general election. In other words, we show that a competitive primary draws people into the process and increases turnout in the general election, but a competitive primary does not affect the party’s electoral fortunes in November.

Third, we find that divisiveness, or the presence of a Tea Party candidate, did not affect the turnout rate in the 2010 general election. Yet, we find that if there was both a competitive Republican primary and a Tea Party candidate in the general election then turnout in the general election was, on average, 1.52 percent higher than a race where there was neither a competitive Republican primary nor a Tea Party candidate. Again, an increase in turnout of this size is significant when considering the low average turnout rate in midterm elections. The combination of competitive primaries and the presence of the Tea Party on the November ballot appears to bring additional voters to the polls.

Finally, we conclude that divisiveness does influence Republican success. More specifically, in races where there was a Tea Party candidate in the general election, the Republican Party garnered a larger vote share than was otherwise expected. More precisely, our results demonstrate that when there was a Tea Party candidate in the general election, the Republican Party performed about 1.7 percent better than expected when compared to races where the Republican candidate was not affiliated with the Tea Party. When looking at the effects of competitive primaries and divisiveness in conjunction, we determine that while a competitive primary is beneficial to the Republican Party as is the presence of a Tea Party candidate on the ballot, if both occur together, this situation is no more advantageous for the party than having a Tea Party candidate on the ballot without a competitive Republican primary.

Overall, our findings suggest that while competitive primaries may not be the best way for a party to secure an electoral advantage in the general election, competitive primaries increase turnout in the general election. On the other hand, a division within the party, as the Republican Party experienced in 2010 with the presence of the Tea Party, may actually be helpful to the party by increasing the party’s share of the general election vote total. This advantage may be the result of additional media attention and increased voter interest in the electoral process and Tea Party policy issues. The Tea Party was able to convince citizens that the 2010 election was pivotal in determining the future direction of the country, which likely caused voters to support the Republican Party to a greater extent than otherwise would have occurred. While the 2010 congressional election is somewhat of an anomaly given the presence of the Tea Party and the deep fissure within the typically cohesive Republican Party, it allows for an ideal test of the simultaneous effects of competitiveness and divisiveness.

Beyond our investigation, an open question is whether a division within the party provides short-term benefits and an electoral advantage as voters become interested and aware, but if the division persists for several elections whether voters may turn toward the more cohesive party or become disinterested and simply stay home. In other words, will the benefit the Tea Party brought to the Republican Party continue to persist or will this party division eventually harm the GOP at the polls?

This article is based on the paper, ‘Competitive primaries and party division in congressional elections’, in Electoral Studies.

Featured image credit: sobyrne99 (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/Z6NYJ7

_________________________________

Caitlin Jewitt – Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University

Caitlin Jewitt – Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University

Caitlin Jewitt is an Assistant Professor of political science at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. Her research agenda focuses on the institutional rules of elections, primary elections, and voter behavior. She is currently working on a book project examining the electoral rules surrounding presidential primaries and caucuses in the United States.

_

Sarah Treul – University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Sarah Treul – University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Sarah Treul is an Assistant Professor in the political science department at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her research agenda focuses on decision making in the U.S. Senate, the role of state delegations in Congress, and primary elections. She is currently working on a book project analyzing how state delegations are utilized in today’s Congress.

Originally a GOP ‘liberty’ caucus initiated by Ron Paul (Rand’s father), the Tea Party movement in the GOP has always been a Republican Party initiative. Tea Party = Republicans.