Many commentators have expressed concern that Congress has not yet taken a formal vote to authorize the use of military force against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIL). In new research, René Lindstädt and Ryan J. Vander Wielen explore why Congress is so reluctant to put issues such as this to a vote around election time. By analyzing party votes, where one party votes in opposition to the other, they find that members are more likely to vote with their party when elections are distant, but as they become nearer, this likelihood falls, as members become concerned about electoral reprisals from their constituents. This means that party leaders are far less likely to schedule highly partisan votes close to an election, for fear of losing votes and seats.

Many commentators have expressed concern that Congress has not yet taken a formal vote to authorize the use of military force against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIL). In new research, René Lindstädt and Ryan J. Vander Wielen explore why Congress is so reluctant to put issues such as this to a vote around election time. By analyzing party votes, where one party votes in opposition to the other, they find that members are more likely to vote with their party when elections are distant, but as they become nearer, this likelihood falls, as members become concerned about electoral reprisals from their constituents. This means that party leaders are far less likely to schedule highly partisan votes close to an election, for fear of losing votes and seats.

Despite the threats presented by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) and U.S. involvement in fighting the group, Congress has yet to take a formal vote to authorize U.S. military involvement. If anything, Senate Democrats and House Republicans alike appear to have little interest in taking up a vote prior to the November elections. Why is Congress reluctant to put this weighty question to a vote?

In recent research, we argue that both chambers are trying to avoid presenting their members with difficult choices close to the elections. In some races, like the North Carolina Senate race, this issue has been front-and-center, putting incumbents in an uncomfortable spot between voters who oppose further military action in the Middle East and those who believe that some action against ISIL is necessary. And neither party is immune to these tensions. As a result, and despite the gravity and time-sensitivity of the situation, party leaders in Congress accept that it is better to wait with the vote. House Speaker John Boehner (R-OH) openly notes that he would recommend a vote after the New Year if the U.S. were still involved in the effort at that time. Quite simply, a vote after the election entails fewer risks to rank-and-file members and makes them more likely to support their party leadership.

The electoral system in the U.S. has forced a very specific brand of partisanship on party leadership and rank-and-file members. With few exceptions, most candidates still run for election on a major party ticket. As long as parties have a well-defined brand, party labels provide meaningful information to voters, who use party labels as a simple cue to evaluate candidates’ policy stances. At the same time, voters also have a strong dislike for partisanship. They want their representatives to be independent and not too tightly bound to their parties. This puts parties in a difficult position. They must exercise party discipline to make policy that sustains the party label, but at the same time, must stay away from excessive demands of loyalty from their rank-and-file membership to avoid alienating voters. Members of Congress and their parties have found a way to address these contradictory mandates. The key is the timing of partisanship.

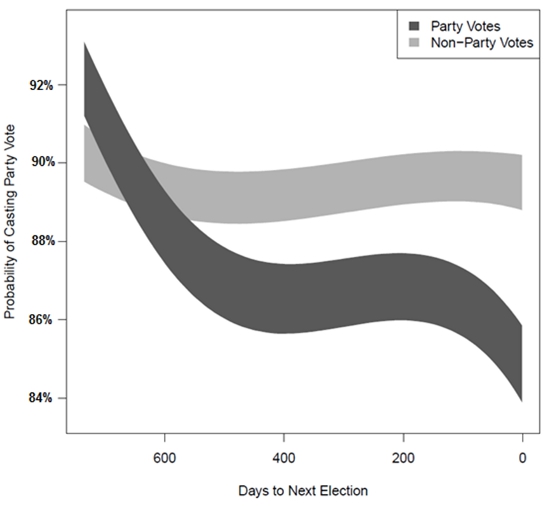

By analyzing party votes – votes in which a majority of one party votes in opposition to a majority of the other party (i.e., party line votes) – within two-year congressional terms, we find that party discipline rises and falls depending on how close votes are to Election Day. Specifically, members are willing to lend their party high levels of loyalty when elections are distant, but temper that loyalty as elections approach. Figure 1 shows the change in probability of a member voting with his/her party over the election cycle for party votes, which are most likely to build a party brand but also result in electoral reprisal, and non-party votes, which do not present members with this tension. The pattern we observe on party votes reflects recognition by members that party support has real value, as well as real electoral consequences. By strategically timing their party loyalty, party members can further the party brand and minimize individual electoral risk.

Figure 1 – Probability of member voting with party over the election cycle

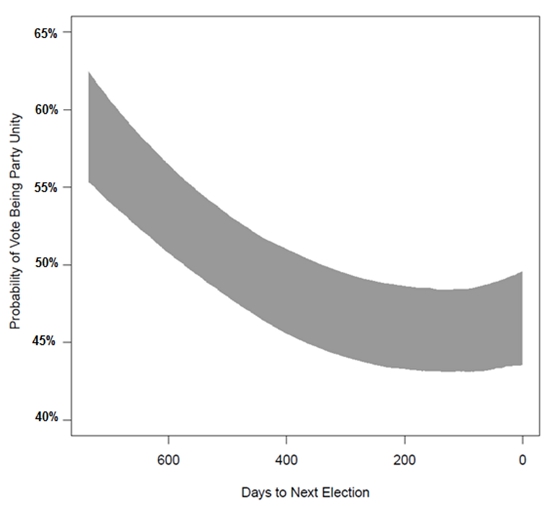

What’s more, party leaders are willing to let the rank-and-file vote their (or their constituent’s) conscience in close proximity to elections, since they seek to maximize the number of seats they hold in the chamber. They do this by strategically adjusting the agenda with respect to elections. Party leaders refrain from scheduling highly partisan votes when elections are near. Instead, contentious partisan votes that divide the parties are typically reserved for the beginning of a new term, with the expectation that the rank-and-file will toe the party line at that time. This can be seen in Figure 2, which shows the precipitous fall in the probability of party votes over the election cycle. Such appears to be the fate of the ISIL authorization vote. This arrangement works because voters have short-term memories and tend to more heavily weigh recent legislative behavior. Moreover, media scrutiny of legislative activity tends to be very different depending on the time in the election cycle.

Figure 2 – Probability of party votes over the election cycle

This article is based on the paper, ‘Dynamic Elite Partisanship: Party Loyalty and Agenda Setting in the US House’, in the British Journal of Political Science.

Featured image credit: United States Government

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/Zbfch7

______________________

René Lindstädt – University of Essex

René Lindstädt – University of Essex

René Lindstädt is Head of Department and Professor in the Department of Government at the University of Essex. He is also Director of the Essex Summer School in Social Science Data Analysis and Co-Editor of the British Journal of Political Science. His main research and teaching areas are political economy, political institutions, formal theory and political methodology. His theoretical interests are in social learning and diffusion, political accountability, strategic communication and cooperation. René’s research has been published in, among others, the Journal of Politics, the British Journal of Political Science, and Comparative Political Studies. His ongoing research includes projects on electoral competitiveness, the political economy of organizational growth, globalization preferences, and temporal dynamics of political accountability.

Ryan Vander Wielen – Temple University

Ryan Vander Wielen – Temple University

Ryan Vander Wielen is an Associate Professor of Political Science and (by courtesy) Economics at Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. His research and teaching interests are in the areas of American Political Institutions, Quantitative Methodology, and Formal Modeling. Much of his work focuses on strategic legislative behavior, and his articles have appeared in such journals as the British Journal of Political Science, Legislative Studies Quarterly, Political Analysis, Public Choice, and Political Research Quarterly.