The dominant narrative around recidivism in America is that most released offenders go on to reoffend and return to prison. In new research, William Rhodes argues that this impression is wrong and that two out of every three released offenders never return to prison. He argues that previous estimates about recidivism have failed to take into account the overrepresentation of returnees in prisons. Accounting for this factor, he finds that only 11 percent of offenders return to prison more than once, and that the total time that offenders actually spend in prison is overestimated as well.

The dominant narrative around recidivism in America is that most released offenders go on to reoffend and return to prison. In new research, William Rhodes argues that this impression is wrong and that two out of every three released offenders never return to prison. He argues that previous estimates about recidivism have failed to take into account the overrepresentation of returnees in prisons. Accounting for this factor, he finds that only 11 percent of offenders return to prison more than once, and that the total time that offenders actually spend in prison is overestimated as well.

A common impression, reinforced by recent statistical reports, is that most offenders released from American prisons return repeatedly. The impression is wrong. Our analysis of offenders released between 2000 and 2012 shows that two of every three never return to prison. Many others reappear just once – typically for violating the technical conditions governing their community supervision instead of for new crimes.

An analogy explains why recent statistical reports are misleading and how statistics based on prison releases and readmissions can be corrected. When performing mall intercept surveys, researchers randomly sample shoppers who appear in the mall during the period when the survey is administered and ask respondents questions such as: How frequently do you visit a mall? Obviously, frequent mall visitors are overrepresented in intercept surveys, so when they analyze survey data, statisticians weight the data to correctly represent all mall visitors.

Offenders who repeatedly return to prison are like frequent mall visitors – they are overrepresented in samples used to estimate the rate at which offenders return to prison. If a statistician fails to weight his statistics to correct for this overrepresentation, offenders will appear to be highly recidivistic: One of every two will return to prison within five years. If the statistician correctly weights her statistics, offenders appear less recidivistic: Two of every three will never return.

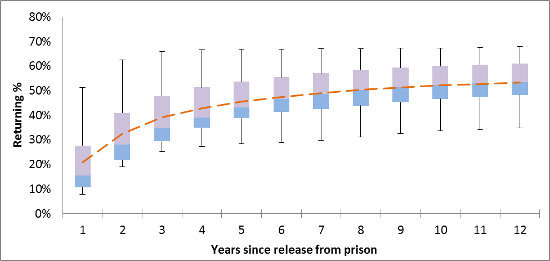

Some graphs illustrate these distinctions. Figure 1, based on data from the National Corrections Reporting Program (NCRP), shows the rate at which offenders return to prison when data are not weighted. Years since being released from prison appear on the horizontal axis. The cumulative percentage of offenders returning to prison appears on the vertical axis. The broken line is the average across seventeen states reporting from 2000 through 2012. (The figure changes little when states reporting for fewer years are included in the analysis.) The boxes show the range for the states at the 1st and 3rd quartiles; the bars show extremes. Consistent with conventional wisdom, unweighted data imply that fifty percent of offenders return to prison, typically soon after being released. Recidivism is higher in some states (California is the extreme high state) and lower in others partially because of differences in how states use prisons.

Figure 1 — Unweighted Data Show a High Rate of Returning to Prison

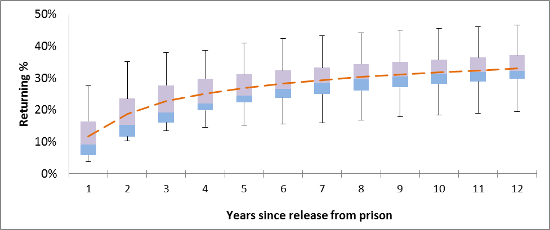

When the data are weighted to represent the population of individuals who enter and exit prison, the return rate is shown in Figure 2. According to the statistics reported in the second figure, two of three offenders will not return to prison within twelve years, and the curve is so flat in the latter years that two of three probably approximates the lifetime limit. Correctly weighting the data produces a startling change in recidivism statistics.

Figure 2 — Weighted Data Show a Lower Rate of Returning to Prison

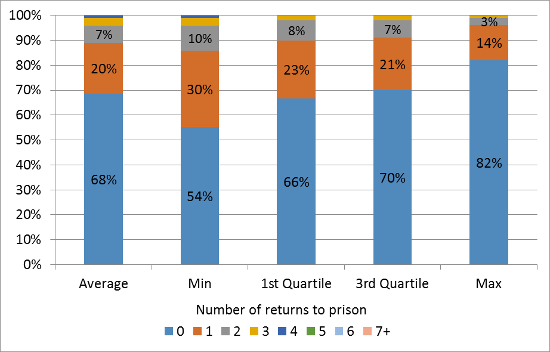

The figures do not show the frequency of returning multiple times, but Figure 3 provides estimates. The chart reports the minimum and maximum, the 1st and 3rd quartiles, and the average across the seventeen states for offenders at risk for twelve years. The table is based on weighted data.

Figure 3 – Frequency of returning to prison over twelve years based on weighted data

Consistent with figure 2, about two of every three offenders (68 percent) never return to prison. Another 20 percent return just once. The NCRP data are not definitive but it appears that most of these one-time returns are for violating the technical conditions governing community supervision rather than for new crimes. Importantly, only one in ten offenders (11 percent) returns to prison multiple times.

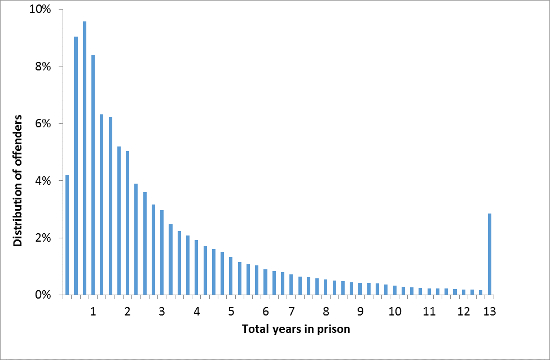

Of course repeated visits to prison may be rare because prison terms are so long that little opportunity exists to exit prison, recidivate and reenter prison, and then exit again, but Figure 4 suggests otherwise. The figure shows the distribution of total time spent in prison across the seventeen states for everyone who was eighteen or older as of 2000. (The NCRP excludes juvenile records.) For example, if an offender spent two years in prison for one term and three years for a subsequent term, the offender would have spent five years in prison between the beginning of 2000 and the end of 2012.

Figure 4 – Distribution of Time Spent in Prison over Thirteen Years

A small proportion of offenders, those who commit the most heinous crimes such as murder and rape, spend the entire thirteen-year period in prison, but most offenders spend considerably less time. If earlier recidivism studies imply that a large proportion of offenders spend most of their lives in prison, this figure suggests otherwise. Prison disrupts lives but apparently it does not consume them.

State and federal authorities may send too many offenders to prison; prison terms may be too long; and correctional resources might be better spent. These statistics do not inform the debate on those topics. But we contest the common perception that American prisons are a revolving door serving to cycle offenders through multiple terms until offenders get too feeble to victimize the public. The evidence is that most offenders serve their time and then avoid serious entanglement with the criminal justice system. Rather than asking the question of why so many offenders fail following release from prison, a more important question may be why so many offenders succeed and how corrections can promote success?

This article is based on the paper, ‘Following Incarceration, Most Released Offenders Never Return to Prison’, in Crime & Delinquency.

Featured image credit: Ken Teegardin (Flickr, CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1sPkASX

_________________________________

William Rhodes – Abt Associates

William Rhodes – Abt Associates

William Rhodes is a principal scientist at Abt Associates, a public policy consulting firm in Cambridge, Massachusetts. An economist, he specializes in program evaluation and quantitative analysis. He is co-principal investigator for the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ (BJS) National Corrections Reporting Program.

This paper makes a novel and important methodological contribution to the understanding of recidivism in America, but I am concerned about the narrative that might come of it. While this shows the numbers are not objectively accurate and would be lower in magnitude if weighted, I believe that in reality it shows a point that is largely useful only in the academic realm, where competition for ‘most accurate’ matters most. In the policy world, this would likely be misinterpreted as we don’t need to invest funds in an already severely strained system focusing on evidence-based decision making and reintegrative practices, due to this conclusion that we are actually much more ‘successful’ at preventing crime and rehabilitating offenders.

From a more nitpicky methodological standpoint, I don’t see this paper mentioning anything about those in the supervised population (on probation, for example) who are revoked to prison, which we know is a large percent of ‘returnees’ and, because it is reported at the national level, the general claims of it might not be so generalizable after all (we all know how much these things vary from state to state, not just in definition, but in policy).

Furthermore, many of the statements made seem to inaccurately represent the point that this is a statistical paper done by a well-known economist and statistician, not a policy recommendation paper by a criminologist or policy researcher. For instance, the statement that “[m]any others reappear just once – typically for violating the technical conditions governing their community supervision instead of for new crimes.” Acknowledges that it might be better to not return multiple times, but to say that 1 in 3 returns once isn’t far off from the conventional understanding of recidivism statistics (at least those that are compiled for a three year follow-up level among the most conservative definitions of recidivism). And by ‘weighting out’ those repeat returnees we are really only mitigating the effect of the concentration of returns among a small percent of offenders. It should be apparent to most who know criminological literature, that crime in our communities is often concentration among a much smaller group of individuals in crime-prone areas, and, hence, to weight out the repeat offenses of these repeat offenders would fall somewhere along the lines of saying that less crime occurs than we ostensibly know, which, hopefully, is not an accurate statement to most. “Prison disrupts lives but apparently it does not consume them.” Is a charged statement that only reflects on the direct effect of exposure to prison and not the ‘overlooked’ consequences such as legal fees, disrupted familial responsibilities and the such. And to say that “that most offenders serve their time and then avoid serious entanglement with the criminal justice system” is ironically true, but not in the sense intended as I see it here. Instead, it says that offenders may be better at not being ‘entangled’ by not getting caught, an argument which could be further bolstered by the fact that criminals end up spending time with more criminals with ‘nothing better to do’ than to learn from each other’s’ criminal wisdom and, in addition, breed cynical attitudes towards the law. I understand that this partly refutes my argument, but either way, it doesn’t lend weight to the argument, in general, put forth here by this paper.

I would also like to add that comparing collection and reporting of recidivism stats to a public opinion survey in a mall seems to be a misconception on many levels. For example, it’s commonly known that most re-offenses counted as recidivism are committed within the same state, thus weighing truth towards the fact that (at least when recording convictions as recidivism and, if we believe these figures are accurate) we do have nearly all the information from the population of interest, not just a small subsample from a biased survey. And just as the conventional wisdom acknowledges (along with this paper), recidivism tops off at a certain point in time, further suggesting that general recidivism reporting is not just a ‘snapshot’ of circumstances.

While this is a valuable contribution to how we think about our recidivism statistics, I believe that all it really tells us for sure is that we need to collecting these statistics in a universal and comprehensive manner.

I would just like to say that inmates end up back in prison due to correction facilities. They play so many games with inmates. I know I’m going through it right now. They get their release and they take a month to get their paperwork done so they can move on,with life. The correction facilities constantly telling them that they are a nobody and they never will be anything. It’s constant harassment on these inmates. They DOC turn their backs on assaults, rape in prison.

I personally know a young man who did his time, got discharge papers but the halfway house is taking their time on releasing him. It’s been 4 weeks and he’s still locked up. He has a good job, saved up over $2000.00, and got an apartment. They just kept playing games with him so yes he did wrong by taking off. Now if and when he is caught he has to go back to prison.

My friend got discharged on may 19th,, he’s still waiting for final papers to get done.

How can they have a chance to prove themselves when the DOC play these games?