Economic headlines have come to dominate media reports in our contemporary 24/7 news cycle. But how are economic changes reflected by the media? By comparing more than 30,000 news stories from the New York Times and The Washington Post with economic and consumer indicators, Stuart Soroka, Dominik Stecula, and Christopher Wlezien, find that the media and public opinion react to economic changes, rather than the overall state of the economy. They also find that media reports tend to reflect future economic expectations, rather than what is presently occurring, or has happened before.These findings have important implications for political leaders, in that they cannot simply rely on general economic indicators – they will be judged more on recent and future economic changes.

Economic headlines have come to dominate media reports in our contemporary 24/7 news cycle. But how are economic changes reflected by the media? By comparing more than 30,000 news stories from the New York Times and The Washington Post with economic and consumer indicators, Stuart Soroka, Dominik Stecula, and Christopher Wlezien, find that the media and public opinion react to economic changes, rather than the overall state of the economy. They also find that media reports tend to reflect future economic expectations, rather than what is presently occurring, or has happened before.These findings have important implications for political leaders, in that they cannot simply rely on general economic indicators – they will be judged more on recent and future economic changes.

Public perceptions of the economy have important consequences, for both politics and the economy. Governments are re-elected, or rejected, based on economic perceptions. Public support for changes in various policy domains, from health or education to foreign affairs, can hinge on attitudes about the economy. Consumption behavior is also affected by the perceived state of the economy, not just personal circumstances, but national circumstances as well.

Despite the importance of public perceptions of the economy, its sources and dynamics are underexplored. We know that public perceptions of the economy are not based on the economy alone. Most individuals have direct experience with only a small part of the national economy, and much of what they believe about national economic circumstances comes from mass media. It is of further significance, then, that mass media do not (and likely cannot) provide a perfectly accurate picture of the economy. A wide range of factors — including space constraints, newsroom organization, journalists’ interests and expertise, and an interest in producing news that attracts audiences — conspire to produce systematic tendencies in the way in which the economy is covered.

These are the insights underlying our recent work exploring the relationship between the economy, media coverage of the economy, and public economic perceptions. Existing research has focused on issues such as the tendency for media to focus more on negative information than on positive information, or on the ways in which media coverage of the economy is different under Democratic versus Republican leadership. Our new work focuses on two thus far under-appreciated aspects of the media-economy-opinion nexus. First, both media and public opinion may react more to changes than to levels in economic conditions. For instance media may not report about continued high inflation as much as they report about a change in the inflation rate. Second, media reports may reflect expectations about the future economy more than what we know about current or past economic circumstances. In sum, media coverage of the economy may mostly reflect changes in where the economy appears to be going, as well as where the public thinks the economy is going.

Our effort to identify these tendencies in media focuses on a content analysis of over 30,000 economic news stories from the New York Times and the Washington Post, alongside the Conference Board’s Lagging, Coincident, and Leading Economic Indicators, and consumer expectations from the University of Michigan’s Survey of Consumers. Examining relationships between these series over a 30-year period, we find that the results confirm our expectations. Media do focus more on change than on levels of the economy; they focus more on future trends than on current and past ones; and they reflect, in part, public perceptions as well. Public perceptions have similar tendencies: shifts in public sentiment are a consequence mainly of changes in the leading economic indicators, alongside changes in media tone.

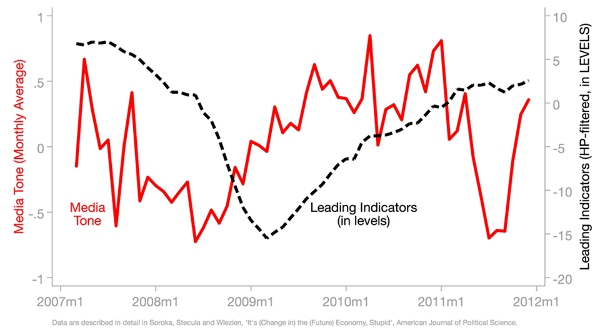

What are the consequences of these patterns in media coverage and public sentiment? One clear implication is that political leaders will tend to be judged not so much the level of the economy, but on recent (and perhaps even prospective) economic change. This is clearly reflected in recent work on the link between campaigns, the economy and election returns; and evident in economic reporting surrounding Obama’s 2012 re-election as well. But this is just one area in which the impact of economic circumstances is focused on prospective changes in conditions. Consider reporting on the Great Recession in 2008/2009. The top panel of Figure 1 shows two lines: one is levels of the leading indicators series and the other is media tone. What accounts for the striking improvement in media tone in mid-2008, given that the economy continues to decline?

Figure 1 – Media Tone and Levels of Leading Indicators

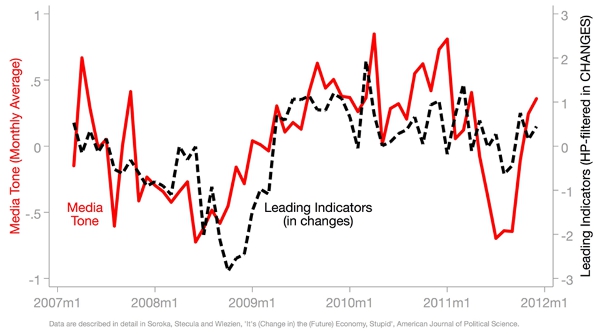

The answer lies in the tendency for media to focus on changes over levels. Figure 2 uses identical data to Figure 1, but in this case leading indicators are shown not in levels, but in changes. In contrast with Figure 1, Figure 2 shows two series that are powerfully related. Media tone may not match well with levels of the economy, then, but it is powerfully connected to changes in those conditions.

Figure 2 – Media Tone and Changes in Leading Indicators

Whether these tendencies produce perverse results in elections, or in economic behavior, is an area for further research. But there clearly are consequences for those focused on election campaigns, or those interested in the quality and accuracy of economic reporting. The way in which the economy finds its way into media content, and into both political and economic behavior, may be systematically biased.

This article is based on the paper, “It’s (Change in) the (Future) Economy, Stupid: Economic Indicators, the Media, and Public Opinion”, in the American Journal of Political Science.

Featured image credit: MyEyeSees (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-ND-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of U.S.App– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1Aitatc

_________________________________

Stuart Soroka – University of Michigan

Stuart Soroka – University of Michigan

Stuart Soroka is the the Michael W. Traugott Collegiate Professor of Communication Studies and Political Science, and Faculty Associate in the Center for Political Studies at the Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. His research focuses on political communication, the sources and/or structure of public preferences for policy, and on the relationships between public policy, public opinion, and mass media.

Dominik Stecula – University of British Columbia

Dominik Stecula – University of British Columbia

Dominik Stecula is a PhD student in the department of political science at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. He is also a Director of Research at the Piast Institute in Detroit, Michigan. His research interests include the intersection of mass media and public opinion in American and comparative context, as well as research methods, primarily analysis of text as data.

Christopher Wlezien- University of Texas, Austin

Christopher Wlezien- University of Texas, Austin

Christopher Wlezien is Hogg Professor of Government at the University of Texas at Austin. He is coauthor of Degrees of Democracy (Cambridge University Press) and The Timeline of Presidential Elections, and currently is Associate Editor of Public Opinion Quarterly.