The trend of mass suburbanization that followed World War II led to increasing segregation and inequality for minorities. But has this pattern continued in suburbs built since the 1960s? In new research, Deirdre Pfeiffer compares neighborhood characteristics in the over 1,500 post-civil rights suburbs in the U.S. with those in central cities and older suburbs. She finds that African Americans living in newer suburbs experience lower rates of neighborhood poverty and have rates of neighborhood homeownership and college education closer to those of whites than their counterparts in the city centre and older suburbs. She argues that her findings show the importance of large-scale housing growth in the U.S. as opposed to infill development which may strengthen existing patterns of segregation and inequality.

The trend of mass suburbanization that followed World War II led to increasing segregation and inequality for minorities. But has this pattern continued in suburbs built since the 1960s? In new research, Deirdre Pfeiffer compares neighborhood characteristics in the over 1,500 post-civil rights suburbs in the U.S. with those in central cities and older suburbs. She finds that African Americans living in newer suburbs experience lower rates of neighborhood poverty and have rates of neighborhood homeownership and college education closer to those of whites than their counterparts in the city centre and older suburbs. She argues that her findings show the importance of large-scale housing growth in the U.S. as opposed to infill development which may strengthen existing patterns of segregation and inequality.

Although the American suburbs propelled Whites into the middle class after World War II, there is concern that they are now contributing to minorities’ downward mobility. Ferguson, Missouri, the most recent tragedy of police racial brutality, is emblematic of the promise and heartbreak of suburbanization for minorities in the U.S. The majority of Ferguson’s residents are Black, but African Americans hold few elected seats and comprise only about 5 percent of the police force. More than 25 percent of Ferguson’s residents live below the poverty line.

Ferguson is the outcome of massive suburbanization following World War II. This process enabled many Whites to move out of crowded central cities and buy houses in safer, spacious communities on the urban fringe. However, housing discrimination, high housing costs, and other factors excluded minorities from the most advantaged suburban communities and led even middle class households to move to less advantaged suburbs like Ferguson that quickly resembled the segregated, high poverty central city neighborhoods that they sought to escape.

Grouping all suburbs together in assessing their potential to advance minorities’ wellbeing is problematic. Suburbia is comprised of not only older suburbs like Ferguson but also newer suburbs like Schaumburg outside of Chicago, Frisco outside of Dallas, or Rancho Cucamonga outside of Los Angeles (see Figure 1). Unlike Ferguson, these newer suburbs came of age in a post-Civil Rights era of fair housing law, minority socioeconomic gains, and growing racial tolerance. They typically lacked a sense of “who lives where” based on race when minorities moved in, being located far from concentrated poverty in central cities and out of less racially marked farmland and open space areas. These conditions may make minorities better off by forging greater diversity and racial equity in neighborhood conditions.

Figure 1 – Crowd and Participants at Rancho Cucamonga High Powder Puff Football Game

Source: Author

I tested this theory by examining how the neighborhood conditions of similar income households by race differed among the central cities, older suburbs, and post-Civil Rights suburbs in 88 regions nationwide. I defined the post-Civil Rights as places that 1) have at least 75 percent of the homes built in 1970 or after and 2) are located within commuting distance of at least one large city but are not the largest city in their regions. Using these criteria, in 2000, there were 1,510 post-Civil Rights suburbs in the U.S.

I compared the post-Civil Rights suburbs to two other geographies: central cities and older suburbs. Central cities are the largest cities in the regions. Older suburbs are all other places in a region excluding the central city and the post-Civil Rights suburbs.

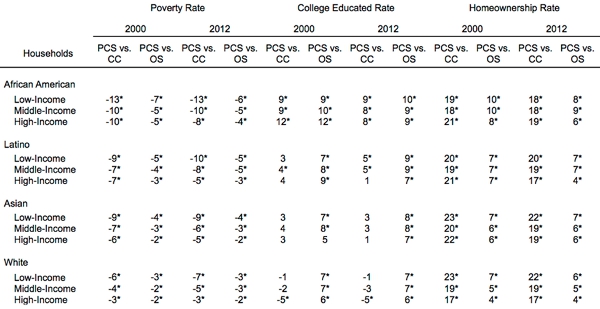

Households across race and income living in the post-Civil Rights suburbs were in neighborhoods with lower poverty rates and higher college educated and homeownership rates on average than their counterparts in the central cities and older suburbs, with few exceptions (see Table 1). The benefits of living in the post-Civil Rights suburbs were greatest for African Americans and low-income households and smallest for Whites and higher income households. The typical low-income African American living in the post-Civil Rights suburbs in both time periods, for instance, was in a neighborhood with an average poverty rate 13 percentage points less than their counterpart in the central city and six to seven percentage points less than their counterpart in an older suburb. This compared to a difference of three to two percentage points for the typical high-income White during both periods respectively.

Table 1 – Average difference in households’ neighbourhood conditions between post-civil rights suburbs (PCS) and central city (CC) and older suburbs (OS) in a region, 2000 and 2012.

Note: Whites are non-Hispanic. Regions with fewer than 100 households for the year and group of interest in either the post-civil rights suburbs, central city, or older suburbs were excluded from the analysis. *Difference significant at 1% level. Source: US Census, 2000, 2013.

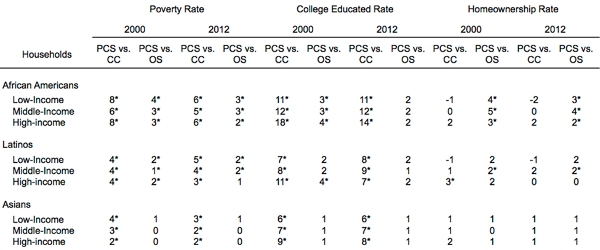

Minorities in the post-Civil Rights also tended to live in neighborhoods with poverty and college educated rates more comparable to similar income Whites than their counterparts in the central city and older suburbs (see Table 2). Gains in the post-Civil Rights suburbs were largest for African Americans and low-income households, and larger compared to the central city than older suburbs. In 2000, the typical low-income African American household in a central city lived in a neighborhood with a poverty rate 10 percentage points greater than the typical low-income White household, compared to only two percentage points greater in the post-Civil Rights suburbs. This amounted to a gain of about eight percentage points in racial equity in neighborhood poverty in the post-Civil Rights suburbs (-1(2-10)=8).

Table 2 – Average gain in racial equity in neighbourhood conditions relative to Whites in the post-civil rights suburbs (PCS) compared to the central city (CC) and older suburbs (OS) in a region, 2000 and 2012

Note: Whites are non-Hispanic. Regions with fewer than 100 households for the year and group of interest in either the post-civil rights suburbs, central city, or older suburbs were excluded from the analysis. *Difference significant at 1% level. Source: US Census, 2000, 2013.

There is concern that the Great Recession and foreclosure crisis accelerated minorities’ downward mobility in the suburbs since they were more likely to have risky loans and undergo foreclosure. Yet, I found that gains in racial equity in the post-Civil Rights suburbs did not fluctuate consistently from 2000 to 2012 (see Table 2). They tended to fall slightly for African Americans and high-income Latinos, but they remained the same or increased for Asians and low- and middle-income Latinos.

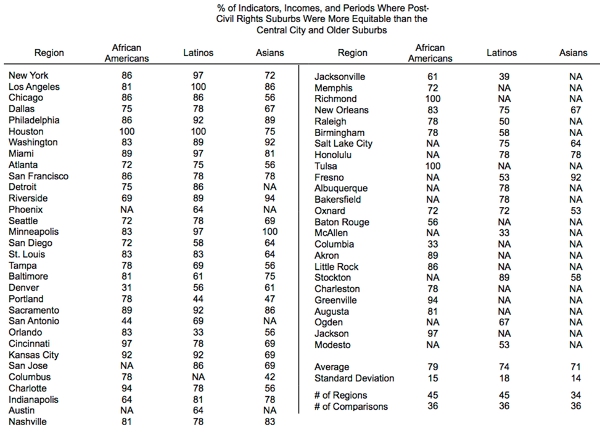

In turn, although conditions for minorities in the post-Civil Rights suburbs varied by income group, indicator, and time period, they were more racially equitable the majority of the time (see Table 3). In nine regions, conditions were more racially equitable in the post-Civil Rights suburbs close to or fully 100 percent of the time. These included Houston for African Americans and Latinos and Minneapolis for Latinos and Asians. The newer the housing stock in the post-Civil Rights suburbs relative to the central city and older suburbs, and the greater their racial integration and income parity among racial groups, the more equitable their conditions.

Table 3 – Regional variation in gains in racial equity in the post-civil rights suburbs

Note: Whites are non-Hispanic. N/A indicates that the region was excluded for not having at least 100 households in the geographies for all periods, indicators, or income groups. Regions not meeting this criteria for all racial groups were excluded from the table. Source: US Census, 2000, 2013.

These findings suggest that fears of growing racial inequality in newer suburbs in the wake of the economic downturn may be overstated. Further, by showing that newer suburbs have forged greater racial equity in neighborhood conditions, they illustrate the importance of allowing for large-scale housing growth within U.S. regions. Attempts to redirect resources toward small-scale infill development in places where there is already a tradition of who lives where based on race may slow or reverse minorities’ gains in racial equity.

This article is based on the paper ‘Racial equity in the post-civil rights suburbs? Evidence from US regions 2000–2012’, in Urban Studies.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1EPCzvJ

_________________________________

Deirdre Pfeiffer – Arizona State University

Deirdre Pfeiffer – Arizona State University

Deirdre Pfeiffer is an Assistant Professor in the School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning at Arizona State University. Her research interests include housing strategies to meet the needs of America’s aging and diversifying population, the outcomes of the recent U.S. Great Recession and foreclosure crisis, and the relationship between urban growth and racial equity. Her current research appears in Urban Studies, Housing Policy Debate, and Journal of Urbanism.