The former Secretary of State, and likely 2016 presidential nominee for the Democratic Party, Hillary Clinton has, along with the Obama administration, pushed the concept of ‘smart power’ – a convergence of hawkish ‘hard’ and a more internationalist ‘soft’ power in U.S. international relations. Cerelia Athanassiou argues that rather than truly signalling a departure from the pre-2008 policies of George W. Bush, this move to ‘smart power’ is actually a rebranding of previous tactics which co-opts ‘soft power’ ideas of engagement to work alongside a still strong national security state.

The former Secretary of State, and likely 2016 presidential nominee for the Democratic Party, Hillary Clinton has, along with the Obama administration, pushed the concept of ‘smart power’ – a convergence of hawkish ‘hard’ and a more internationalist ‘soft’ power in U.S. international relations. Cerelia Athanassiou argues that rather than truly signalling a departure from the pre-2008 policies of George W. Bush, this move to ‘smart power’ is actually a rebranding of previous tactics which co-opts ‘soft power’ ideas of engagement to work alongside a still strong national security state.

The 2016 campaign frenzy is slowly revving up, with Hillary Clinton being hailed by many as a feminist icon: one that has reached unprecedented heights in terms of female political leadership and who has kept women’s rights on the international agenda when representing the US on the world stage. She is inevitably being characterised as a portent of change who deserves liberals’ and feminists’ support to break through male domination of US politics. I want to offer a sceptical perspective on ‘change’ as promised by leader figures like this; not necessarily to break up celebrations of a woman presidential candidate, but certainly to interrupt this flow with what I hope are productive questions about expectations of change, leadership and politics. A lot of this work can be done on a conceptual level, as I do here by analysing the gendered workings of the now pretty conventional notions of ‘soft’, ‘hard’ and ‘smart’ power.

Clinton’s tenure at the Department of State (now marred somewhat by her ‘Emailgate’ scandal) ran under the banner of ‘smart power’ – a concept that provides a convenient convergence between more hawkish and more internationalist approaches to foreign policy. This is a concept that merges the two types of power theorised by Joseph Nye: ‘soft’ and ‘hard’. Importantly, ‘smart power’ provided an excellent driver for the Obama administration’s ‘era of engagement’, which was introduced after a period of what we might want to refer to as Bush-era militarised unilateralism. This seeming paradigm shift resonated with the more general feeling among liberal observers of US politics that US unilateralism had been unproductive under Bush. This is based on the reasoning that the ability to persuade is an important strategic tool for the US. In this sense, change was clearly on the agenda for the new administration, though it is easy to find a consensus now that delivery on this change was not as effective. A quick run-through of the conceptual framework of ‘smart power’ can more explicitly show some inconsistencies that are worth attending to, especially because reliance on them will continue with Clinton’s anticipated return to the campaign trail later this year.

Gendering smart power

Nye’s conceptualisation of power took an explicitly gendered turn in 2012, when he challenged what he identified as the traditional masculine approach to governance and leadership that focuses more on concentration of power hierarchically rather than distributing it. Nye stresses that this difference in style of leadership corresponds to gender norms and he points to essential differences between women’s and men’s leadership; his argument is that a ‘softer’ approach to power, corresponding to qualities that are seemingly essentially possessed by women, is necessary in dealing with political complexity:

[m]odern leaders must be able to use networks, to collaborate, and to encourage participation. Women’s non-hierarchical style and relational skills fit a leadership need in the new world of knowledge-based organizations and groups that men, on average, are less well prepared to meet.

The distinction between ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ correlates to differential dynamics of masculinity and femininity: in the conduct of international politics, certain qualities are feminised, others are masculinised (this differentiation being relative), with the core holding these together seeming gender neutral. Nye bases his theory on the differentiation between vertical, hierarchical masculinity (hard power) and a more distributive femininity (soft power), but ignores the fact that this differentiation is held up by an assumed vertical masculinity whose gender is never made explicit. As a consequence, Nye’s essentialist conception of gender prevents him from questioning this core, concluding rather that adding women and their ‘style’ to this unproblematic and neutral core will bolster it. When Nye poses his key question as whether ‘gender really matters in leadership’, he is already communicating the wrong assumption that leadership can be viewed as de-gendered in the ‘smart’ transcendence of ‘soft’ and ‘hard’. I see this as a crucial blindspot in Nye’s, and subsequently the Obama administration’s, theorizing, and practising of (gender in) international politics. This blindness has significant consequences for how we understand and ‘do’ change.

In the Obama administration’s ‘doing’ of change, ‘engagement’ as the opposite of a militarized politics constituted a greater openness and flexibility of choice of tactics or policies. And so, renewed faith in the rules governing international relations has been articulated. What is seen as necessary in this internationalist approach is not just a well-resourced military arm, but also a ‘soft’ connection with the outside world, which is provided through careful investment in varied diplomatic efforts, to produce ‘a blend of principle and pragmatism’. Flexibility in this changed approach requires recognition that an effective foreign policy has to allow for transcendence of ‘soft’ and ‘hard’, rather than opting for one over the other. This has, more often than not, simply meant fallback on familiar militarised tactics when necessary, with ‘smart power’ being openly referred to as a tactic in rebranding, or reconceptualisation: ‘Smart power’ demands that ‘Washington must reconceptualize the fight against terrorism and WMD as a sustained effort to expand freedom and opportunity.’ Thus, ‘soft’ ideas of democratic ‘engagement’ merely serve to support the traditionally ‘hard’ and strong national security state. As in the typology offered by Nye, ‘smart’ power does not signify the overriding of ‘hard’ militarising strategy, but seeks ‘soft’ tactics to bolster it.

Questioning change

Nye makes his argument for ‘smart’ power by drawing a distinction between ‘women’s non-hierarchical’ style of leadership as the opposite to men’s more competitive and conflictual style. In this, his essentialist argument mirrors the Obama administration’s strategy on ‘engagement’ as a ‘soft’ tool in the larger arsenal required to confront a ‘hard’ world. Thus, the discourse of ‘smart’ power is one that operates insidiously, basing itself on problematic and dangerous framings of gendered presuppositions. It poses as a discourse of emancipation, luring listeners to its imagery of rights, democracy and security, but is only interested in perpetuating a binary that is instrumental in propping up conventional understandings of ‘national security’; the ‘smart’ problematic only works to privilege the ‘hard’, subjecting ‘soft’ approaches to its dictates.

For observers of US foreign policy and politics more generally, charismatic and interesting figures like those of Obama and Clinton pose a genuine dilemma about the ability and willingness of the political classes to bring about socio-political change that would resonate with the popular expectations that get them into office in the first place. There is change to be observed between the Obama administration and his predecessor’s foreign policy, and there is much that can be said of Clinton’s feminism. There is also room to examine the inconsistencies of these figures’ attempts at change and some of their shortcomings in relation to what is expected of them. Exposing ‘smart power’ as a rebranding tactic is one way of holding to account their largely unchanging politics.

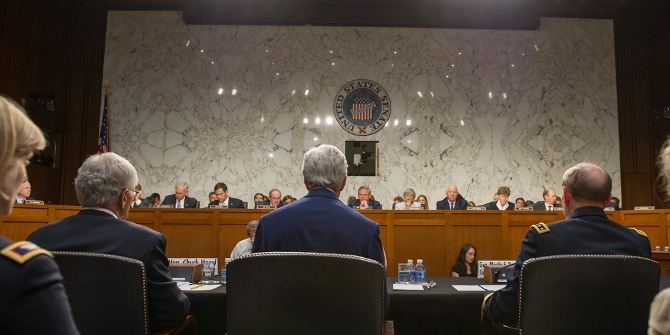

This article is based on a talk given at the LSE US Foreign Policy Conference held on September 17-19th, 2014. You can watch video highlights from the conference in the player below:

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1I5Q8MQ

_________________________________

Cerelia Athanassiou – University of Bristol

Cerelia Athanassiou – University of Bristol

Cerelia Athanassiou’s research draws on feminist security studies and discourse theory to analyse attempts in recent years to ‘demilitarise’ the discourse of the Global War on Terror. She is currently a Research Associate at the University of Bristol and a practitioner of soft power in her role as Business Development Manager for the global training provider, GnosisLearning.