Recent years have seen a renewed focus on the relationship between law enforcement and the communities that they police, with concern arising from perceived bias against Black and Latino populations. If there is concern in these communities about the role of the police, then why do we not see a greater mobilization of communities to protest? In new research, Andres F. Rengifo and Lee Ann Slocum explore the factors influencing community mobilization in the face of intensive policing. Their South Bronx case study suggests that while community organizations do exist and people are engaged, these organizations are not usually politically or civically oriented. Support for the police is also uneven, with many who are concerned about their use of force and unfriendliness potentially discouraged from speaking out due to their own previous involvement with law enforcement.

Recent years have seen a renewed focus on the relationship between law enforcement and the communities that they police, with concern arising from perceived bias against Black and Latino populations. If there is concern in these communities about the role of the police, then why do we not see a greater mobilization of communities to protest? In new research, Andres F. Rengifo and Lee Ann Slocum explore the factors influencing community mobilization in the face of intensive policing. Their South Bronx case study suggests that while community organizations do exist and people are engaged, these organizations are not usually politically or civically oriented. Support for the police is also uneven, with many who are concerned about their use of force and unfriendliness potentially discouraged from speaking out due to their own previous involvement with law enforcement.

In 2011 the New York Police Department conducted almost 700,000 stops. Most stops took place in a few Black and Latino neighborhoods, and less than 10 percent resulted in an arrest or summons. Yet, with the exception of “know-your-rights” campaigns, litigation and “cop-watch” projects, there is little evidence that this practice led to widespread community mobilization at the grassroots level within the neighborhoods bearing the brunt of intensive policing.

What factors may explain this limited mobilization? In new research, we hypothesize that community mobilization around issues of policing may be influenced by 1) organizational infrastructure; 2) resident participation in organizations; 3) attitudes toward neighborhood change; and 4) perceptions of police performance. Our primary focus is the conceptualization of these hypotheses, but we ground our discussion in a case study of the South Bronx — a disadvantaged high-crime area of New York City that is not only heavily-policed but also has a rich tradition of community activism. In the absence of robust measures of community mobilization, we use individual-level survey data and information on the density of organizations and numbers of police stops in neighborhoods in the South Bronx.

Our descriptive work suggests that the South Bronx has many community organizations, significant levels of resident involvement, and general optimism regarding neighborhood change. There is some indication that residents may be willing to put up with frequent “hassles” from the police in exchange for less crime. Our findings are as follows:

1) Organizational Infrastructure

Neighborhood organizations can enhance information sharing among residents and amplify the reach of personal networks by providing access to non-local sources of information and resources. They also provide an umbrella of legitimacy through which residents can air and reformulate their individual problems as collective issues. Thus community responses to NYPD’s stop-and-frisk activity may be inhibited if neighborhood organizations are weak, limited in reach, or distanced from crime and safety issues.

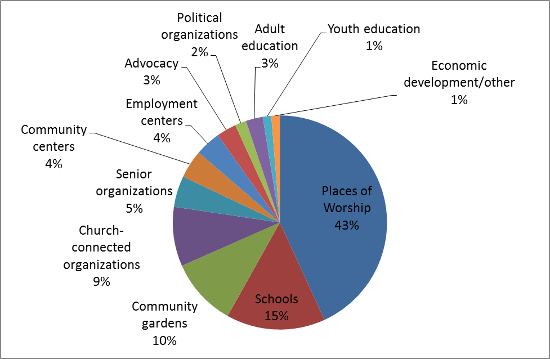

Our census of community organizations indicates there is an infrastructure in place that could help residents of the South Bronx mobilize. However, as noted in Figure 1, the backbone of this structure consists of religious organizations, not organizations with agendas narrowly focused on civic or political issues.

Figure 1 – Community organizations in the South Bronx (N=234)

2) Levels of civic engagement

Collective responses to stop-and-frisk policies may be influenced by the level of civic engagement. Low membership numbers and turnover both in leadership and the membership base can strain the financial and logistical resources of organizations, particularly in poor, minority neighborhoods. Weaker resident support for organizations may force institutions to pool resources and consolidate agendas with other organizations or government agencies.

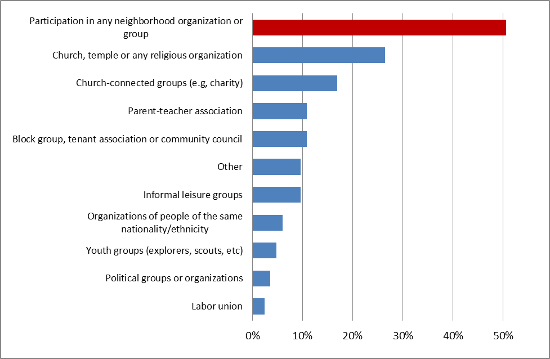

Approximately half of the 83 respondents in our study area participate in a local organization of some type (Figure 2). Participation is lower in organizations that are more narrowly focused on law and order issues.

Figure 2 – Participation in local organizations – South Bronx survey (N=83)

It is also possible participants in these organizations are less affected by stop-and-frisk policies. We find limited support for this idea. Generally, people who live in high stop areas and those who have been personally stopped by the police participate in organizations equal to those who live in neighborhoods with fewer stops and people who have not been stopped.

3) Attitudes regarding neighborhood change

More intense stop-and-frisk practices by the NYPD may have not triggered substantial local, collective responses because residents may lack confidence in the ability of specific forms of collective action to elicit change. Our findings do not support this: over 80 percent of those surveyed believe that it is possible or likely that local organizations can improve neighborhood conditions. About 60 percent of respondents reported that neighbors would be “likely or very likely” to take action to keep a “local firehouse open”.

This optimism is not shared by all residents. Individuals who report criminal justice system contact, both personal and vicarious, tend to have more cynical attitudes regarding the potential for collective processes. Collective mobilization against NYPD’s policies may be limited because the people most affected by them have little faith that organizations or neighborhood residents can enact change.

4) Perceptions of police performance

Residents may be unlikely to engage in collective response to stops if they perceive a connection between more intensive law enforcement practices and lower rates of crime. Furthermore, perceptions of effectiveness may be distinct from beliefs about the fairness or legitimacy of these practices, and in high crime areas residents may believe that intensive policing is the price they must pay for safety, especially if the stops are largely seen by residents as conducted in a procedurally just manner.

Respondents were asked to rate the extent to which the police not responding to calls, using excessive force, and having an unfriendly attitude are problems. The first question captures perceptions of police performance in terms of “outcomes” and the latter two questions measure “process”.

On average we find that generally residents are satisfied with the police, but a closer examination reflects a more nuanced picture. While a relatively large percentage of individuals see the police as posing no problem, a smaller, but sizeable group sees a big problem. This uneven support for the police raises the question, what prevents the group who is largely unsatisfied with the police from organizing to change police policies? One potential explanation is that individuals who are most dissatisfied with the police are least able to mobilize because of their own involvement in crime or the criminal justice system.

We find there is no difference in perceptions of responsiveness between those with and without criminal justice system involvement, including stops, but those who reported criminal justice system involvement perceived that police use of force and unfriendliness are bigger problems in their neighborhoods. These findings support the idea that those who have the strongest incentive for collective action against stops, may not be well-positioned to act on these concerns. They also provide further evidence of the distinction between subjective evaluations of policing outcomes and process and suggest that those with criminal justice system involvement may see the police as effective, but not fair. Still, residents might be willing to accept stops as an effective tool for reducing crime, but may prefer less invasive methods of policing.

This research contributes to ongoing conversations on the architecture of police oversight systems by considering potential pathways of local community engagement and mobilization in connection to discrete police practices, from stops to police shootings. This is important because formal mechanisms of accountability—such as “transparency” and “independence” need to be reassessed in connection to actual practices and specific contexts. These perspectives should consider how communities evolve from rather silent partners in the implementation of community-oriented police models and de-facto checkers of the legality of specific practices to engage in broader conversations on the meaning and production of safety.

This article is based on the paper ‘Community Responses to “Stop-and-Frisk” in New York City Conceptualizing Local Conditions and Correlates’, in Criminal Justice Policy Review.

Featured image: March to end stop and frisk and racial profiling, 2012. Credit: longislandwins (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1CUA3F3

______________________

Andres F. Rengifo – Rutgers University & Harvard University

Andres F. Rengifo – Rutgers University & Harvard University

Andres Rengifo is an Associate Professor at Rutgers University and Research Fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School. His research focuses primarily on the intersection between sentencing policies and imprisonment. He also studies social networks, and policing and urban crime in the United States and overseas.

_

Lee Ann Slocum – University of Missouri St. Louis

Lee Ann Slocum – University of Missouri St. Louis

Lee Ann Slocum is an Associate Professor at the University of Missouri St. Louis. Her recent research explores the consequences of police contact for adolescent development and behavior and assesses how encounters with law enforcement influence people’s willingness to report crimes.