The influence of lobbyists and lobbying by corporations and interest groups has become a fact of life in Washington D.C. In new research, Matt W. Loftis and Jaclyn J. Kettler find that U.S. cities have now also started to lobby Congress in a significant way, spending $150 million on the practice between 1998 and 2008. They argue that cities choose when and how to lobby based on their individual needs and their strategic opportunities; for example, cities with high unemployment rates were almost twice as likely lobby as cities with relatively low unemployment rates.

The influence of lobbyists and lobbying by corporations and interest groups has become a fact of life in Washington D.C. In new research, Matt W. Loftis and Jaclyn J. Kettler find that U.S. cities have now also started to lobby Congress in a significant way, spending $150 million on the practice between 1998 and 2008. They argue that cities choose when and how to lobby based on their individual needs and their strategic opportunities; for example, cities with high unemployment rates were almost twice as likely lobby as cities with relatively low unemployment rates.

When we think of lobbyists in Washington, D.C., we usually think of them representing corporations and big interest groups. However, lower levels of government are increasingly paying to lobby Congress. We collected data from the Center for Responsive Politics showing that, between 1998 and 2008, more than 240 mid-sized U.S. cities across forty-five states hired lobbyists to represent them in D.C. during at least one congressional session. In total, these municipal governments spent almost $150 million in public money to lobby Congress during this time. That works out to an average of $155,000 each, or about $1.15 per capita, every two-year session. These amounts may surprise many of these cities’ residents, especially since U.S. citizens elect members of Congress to represent their local areas’ interests.

Why are cities now spending significant sums of their taxpayers’ money to lobby Congress? A generation ago, American cities mostly lobbied through large public interest groups like the National League of Cities or the United States Conference of Mayors. These big membership-based organizations were established in the 1920s and 30s, respectively, and have since provided the main voice for local governments’ concerns at the federal level. These include issues that unite local leaders, such as: infrastructure investment, supporting the housing market, public safety, immigration, drug abuse prevention, and the like.

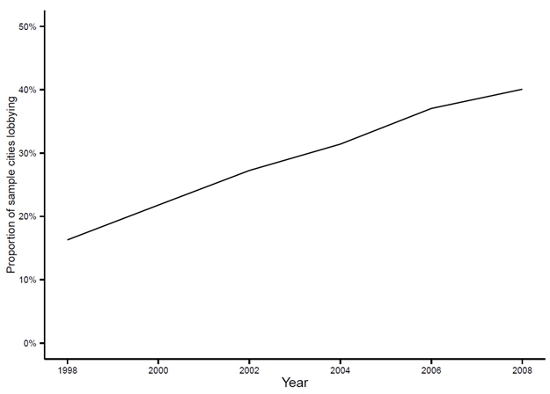

This situation has changed dramatically, however. The big public interest groups remain prominent in national debates, but cities have increasingly hired their own lobbyists to target Congress over the past 15 years. The earliest beginning of the trend can be traced as far back as the 1980s, when the courts affirmed cities’ right to independently lobby the federal government. Good data on lobbying was extremely scarce until the late 1990s, but just between 1998 and 2008 our data show that the proportion of mid-sized cities lobbying more than doubled.

Figure 1 – Proportion of mid-sized U.S. cities lobbying Congress in each congressional session

This is puzzling because it is not a given that hired lobbyists are cities’ best means of influencing Congress. After all, professional lobbyists must register their activities under the Lobbying Disclosure Act and are subject to its restrictions, whereas city and state officials do not face these constraints. Furthermore, hiring a lobbying firm means a city must monitor and manage their relationship with the firm.

This raises two key questions. First, are public interest groups failing in their mission to represent local governments, or are cities responding to new or unique incentives by investing in lobbying? And second, public contracting can be a source of inefficiency and even corruption, so are cities investing resources in lobbying in ways that are rational and effective?

In recent research we argue that cities choose when and how to lobby based on their individual needs and on their strategic opportunities. Whereas the big local government public interest groups lobby for the benefit of all U.S. cities, lobbying by individual cities is about that city’s particular needs. This helps explain why cities choose to invest in lobbying on their own.

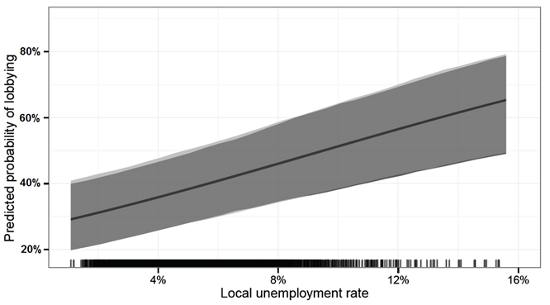

To examine how cities respond to their own needs, we looked for evidence that they decided to lobby in response to increases in the local unemployment rate. We found that cities with high unemployment rates (around 10 percent) were almost twice as likely to start lobbying as cities with unemployment around 3 percent. This pattern held across our sample of 498 mid-sized U.S. cities between 1998 and 2008 (We studied all U.S. cities with a population between seventy-five thousand and six hundred fifty thousand in 1998, whose geographic borders fall mostly into a single congressional district).

Figure 2 – Simulated probability of lobbying for an average city

Shaded spaces are 95 percent confidence intervals around predictions of the probability of lobbying, given unemployment. Light gray is associated with uncompetitive districts; dark gray marks competitive districts. The rug at bottom plots the frequency of actual unemployment in the data.

We also find that cities make lobbying choices in ways that appear quite pragmatic and even strategic. For one, distance matters. Cities geographically closer to D.C. hire lobbyists less frequently than those situated farther away. The average mid-sized U.S. city is about 12 percent less likely to hire a lobbyist than a similar city situated 1,000 miles farther away from the capital. Cities also lobbied more when the majority party in the House of Representatives changed over to the Democrats in 2007. The average city was about 16 percentage points more likely to lobby during that congressional session, relative to other sessions.

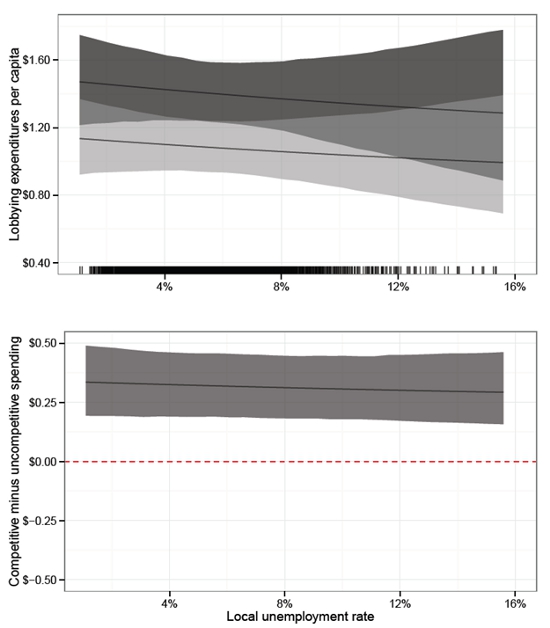

More interesting still is that cities who lobby spent more money doing it when they expected to have more influence in Congress. Previous research has shown that members of Congress from competitive congressional districts, i.e. those with closer elections, are often more successful at getting benefits for their districts. We tested whether cities strategically lobbied more when they were located in a competitive district and found that these cities spent almost 50 percent more, on average, (around $0.35 per capita) than similar cities located in non-competitive congressional districts.

Figure 3 – Simulated per capita lobbying expenditures, for an average lobbying city

Note: Shaded spaces are 95 percent confidence intervals around predictions of per capita lobbying expenditures, given unemployment. In the top panel, light gray is associated with uncompetitive districts; dark gray marks competitive districts. The lower panel shows the difference is statistically significant by simulating the difference between competitive and uncompetitive districts and its 95 percent confidence interval. The rug at bottom plots the frequency of actual unemployment in the data.

By all indications, lobbying by municipal governments is still increasing in the U.S. In contrast to the standard image of lobbying, cities appear to be buying representation in a counter-cyclical attempt to improve their economic fortunes and they are doing so with a strategic eye to their opportunities to influence policy in Congress.

This article is based on the paper, “Lobbying from Inside the System Why Local Governments Pay for Representation in the US Congress,” in Political Research Quarterly.

Featured image credit: Andrew Langdal (CC-NY-NC-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1EC3P0e

_________________________________

Matt W. Loftis – Aarhus University, Denmark

Matt W. Loftis – Aarhus University, Denmark

Matt Loftis is an assistant professor in the Department of Political Science and Government at the University of Aarhus in Aarhus, Denmark. His research focuses on themes of blame-shifting, political accountability, agenda-setting, and transparency. He studies these themes in diverse contexts from both national and local politics in the United States and across Europe.

Jaclyn J. Kettler – Boise State University

Jaclyn J. Kettler – Boise State University

Jaclyn Kettler is an assistant professor at Boise State University in the Department of Political Science. Her research interests include state politics, political parties, campaigns & elections, and women in politics. She is broadly interested in the intersection of U.S. electoral and legislative politics.