This month the Supreme Court is due to announce its decision in the King v. Burwell case, which will determine whether federally-run health care exchanges may provide subsidies to individuals under the Affordable Care Act. Many Republicans hope the Court rules that such subsidies may not be provided under the text of the statute, while some Democrats, including President Obama, argue that the case should never have been heard. But is the public’s opinion of the Supreme Court shaped by such partisan messages? In new research, Tom Clark and John Kastellec find that the public’s opinion of the court is shaped by messages from their co-partisans: among members of the public, Democrats and Republicans are much more likely to support limitations to the independence of the Supreme Court when they are told that such limitations have been proposed by members of their own party. They write that while evaluations of the Supreme Court may be easily shaped by partisan attacks, so long as one party supports its decisions the Court may be insulated from this criticism to some degree.

This month the Supreme Court is due to announce its decision in the King v. Burwell case, which will determine whether federally-run health care exchanges may provide subsidies to individuals under the Affordable Care Act. Many Republicans hope the Court rules that such subsidies may not be provided under the text of the statute, while some Democrats, including President Obama, argue that the case should never have been heard. But is the public’s opinion of the Supreme Court shaped by such partisan messages? In new research, Tom Clark and John Kastellec find that the public’s opinion of the court is shaped by messages from their co-partisans: among members of the public, Democrats and Republicans are much more likely to support limitations to the independence of the Supreme Court when they are told that such limitations have been proposed by members of their own party. They write that while evaluations of the Supreme Court may be easily shaped by partisan attacks, so long as one party supports its decisions the Court may be insulated from this criticism to some degree.

“I think it’s important for us to go ahead and assume that the Supreme Court is going to do what most legal scholars who’ve looked at this would expect them to do.” So said President Obama on June 8th as the Supreme Court prepared to issue its second major ruling on the fate of Obamacare. “This,” he added, “should be an easy case, frankly it shouldn’t have even been taken up.”

President’s Obama prediction—and not-so-subtle rebuke of the justices of the Supreme Court for even entertaining the latest challenge to the health care law—illustrates the ways in which elected officials attempt to both influence what courts do and shape the ways in which their decisions may be received by the mass public. Indeed, in an era of clear distinctions between political parties – ideological polarization – we might expect that political leaders’ comments are particularly useful for constituents trying to form political opinions. What their copartisans think tells them a lot about how the parties divide on the issues. Following the Supreme Court’s initial decision in 2012 upholding Obamacare’s individual mandate, which was followed by intense Republican criticism of the decision, public approval of the Court dropped sharply among Republicans, while Democrats’ approval of the Court increased.

Using a set of survey experiments fielded throughout the Spring of 2012, when the Supreme Court last considered a case on the health care law, we examined whether shifts of this nature are symptomatic of the ways in which cues from other political actors may shape people’s views of the Court. First, we examined how source cues—particularly partisan source cues—might affect support for judicial independence. Specifically, in each survey, we asked respondents the following question: “Federal judges, including Supreme Court Justices, serve during ‘good behavior’ which essentially means for life. Recently, [some people/ some Democrats/some Republicans] have proposed limiting the tenure of federal judges and Supreme Court Justices to 18 years. Do you approve or disapprove of those proposals?” The bolded phrases were randomly assigned to each respondent. Next, we asked respondents: “”It is generally thought that the Supreme Court has the final say on constitutional questions. [Some people/Some Democrats/Some Republicans] have proposed allowing the president and Congress to reverse Supreme Court decisions that they disagree with. Do you approve or disapprove of those proposals?” Again the bolded phrases were randomly assigned.

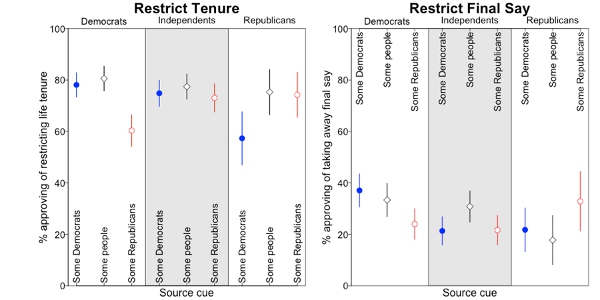

Figure 1 – Responses to survey on Supreme Court life tenure and restricting final say on decisions by partisanship

Figure 1 shows the results from our survey experiments: the left plot shows the mean responses to the life tenure question, broken by the party of the respondent and the type of cue received, while the right plot shows the responses to the final say question.

The patterns are clear, and demonstrate the importance of partisan source cues. Democrats were much less likely to support either proposal to curb the independence of the Court when it was proposed by “some Republicans,” compared to a source cue of either “some Democrats” or “some people.” For example, 78 percent of Democrats approved of restricting life tenure when it is proposed by “some Democrats,” compared to only 60 percent when proposed by “some Republicans.” We see a symmetric pattern with Republicans: they were much less likely to support either proposal when it was proposed by Democrats compared to when it is proposed by Republicans. Finally, among Independents, support for restricting tenure does not vary across source cue; for restricting life tenure, Independents were slightly more likely to support the proposal when it was made a by a neutral source compared to a partisan one.

Next, to evaluate the role of source cues in the public’s beliefs about the extent to which the justices should be able to make their decisions free of external influence, we asked: “The Supreme Court recently heard oral arguments in the challenge to the national health care law. [Many people/Many of the law’s supporters/Many of the law’s opponents] demonstrated out front of the Court. Do you think the demonstrators’ views should influence the Court’s decision in this case?” This question—combined with the fact that we ask respondents their opinion about the health care law itself—was designed to test the degree to which a respondent’s preference for the Court to remain independent (that is, not influenced by demonstrators) is influenced by an individual’s preference over the outcome of the case.

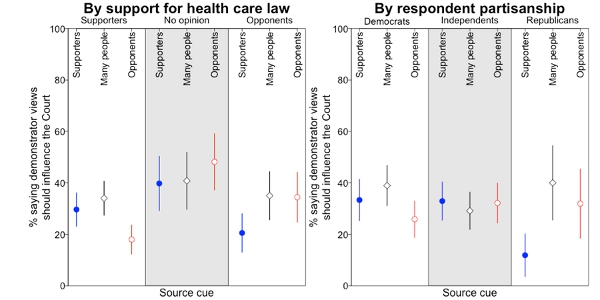

Figure 2 – Responses to survey on influence of Supreme Court demonstrators’ views by support for Obamacare law and partisanship

Figure 2 presents the results: the left plot shows the responses broken down by whether respondents supported or opposed Obamacare (or had no opinion), while the right plot breaks responses by party identification. The patterns are again clear. Among those who wanted to uphold the healthcare law, respondents were less likely to say the Supreme Court “should listen to” protestors when those protestors were described as opponents than when they are described as supporters or “many people.” The converse pattern holds among those who preferred that the Supreme Court invalidate the healthcare law. Respondents were less likely to say the Supreme Court should listen to protesters when those protestors were described as supporters than when they are described as opponents or “many people.” Finally, among those with no opinion on the law, the type of cue does not affect opinion. The right plot tells a similar story with respect to partisanship. Democrats were less likely to say the demonstrators’ views should influence the Court when “opponents” of the law demonstrate, compared to “supporters” or “many people.” The pattern among Republicans is even more striking. Only 12 percent of Republican respondents believed the Court should heed the views of “supporters” of the law, compared to 40 percent when it is “opponents” who are demonstrating.

In conclusion, the results of our survey experiments suggest that the public does not evaluate the Supreme Court in a neutral manner. Instead, we find people key on source cues to evaluate how much independence the Court should have. Given the current era of polarization, these results push in two directions. On the one hand, evaluations of the Court may be easily shaped by partisan attacks on the Court—recall the dip in public support of the Court among Republicans (and, especially Chief Justice John Roberts) following the 2012 Obamacare decision. On the other hand, because one party will usually benefit from a decision made by the Court, the justices may be insulated from an overwhelming attack on their independence from all sides, as long as one party is supportive of its decisions. Thus, the very fact that the Court is viewed in a political lens may help insulate it from partisan attacks.

This article is based on the paper “‘Source Cues and Public Support for the Supreme Court,” published in American Politics Research.

Featured image credit: Adam Fagen (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1ekBh5i

_________________________________

Tom Clark– Emory University

Tom Clark– Emory University

Tom Clark is Asa Griggs Candler Professor of Political Science at Emory University. His current research focuses on the development of learning about and construction of legal rules in appellate courts, as well as the political cleavages and conflicts in American law.

John Kastellec – Princeton University

John Kastellec – Princeton University

John Kastellec is an assistant professor in the Department of Politics at Princeton University. His current research analyzes the dynamics of collegial decision making on three-judge panels of the U.S. Courts of Appeals, with a particular focus on how the judicial hierarchy interacts with collegiality to influence individual judicial voting.