Should presidents try to lead public opinion? Many scholars argue presidents are the most important leaders of public opinion. However, presidents may lose votes if they push issues which are unpopular among voters. Michael Bailey and Clyde Wilcox find that support for President Bush moved in response to voter views of the Iraq War Bush promoted. The implication is that Presidents need to be strategic about their public stances and , instead of going public, may sometimes choose to go silent, even when they could potentially persuade some people.

Should presidents try to lead public opinion? Many scholars argue presidents are the most important leaders of public opinion. However, presidents may lose votes if they push issues which are unpopular among voters. Michael Bailey and Clyde Wilcox find that support for President Bush moved in response to voter views of the Iraq War Bush promoted. The implication is that Presidents need to be strategic about their public stances and , instead of going public, may sometimes choose to go silent, even when they could potentially persuade some people.

Many people want President Obama to speak out more forcefully on climate change, gay marriage, police violence, economic inequality and other issues. Bernie Sanders does it, so why not the President?

Before deciding whether to push a given issue, the President (or other politician) needs to ask two questions: Will I persuade people? Will people like me more (or less?) for trying to persuade them? The academic literature has focused on the first question, while paying much less attention to the second.

Our research suggests that the answers to these questions are intimately connected. If the president takes a strong liberal position, he may be able to persuade some people — likely people who already like him – while suffering loss in votes among people who disagree with him on the issue. If he takes a conservative position, he may get people who already like him to agree with him on the issue, but lose votes among those who disagree with him on the issue.

In new research, we demonstrate the multi-faceted relationship between gaining support and agreement by examining President Bush and the Iraq War. We were particularly interested in whether Bush’s stance on the war affected how much voters liked him.

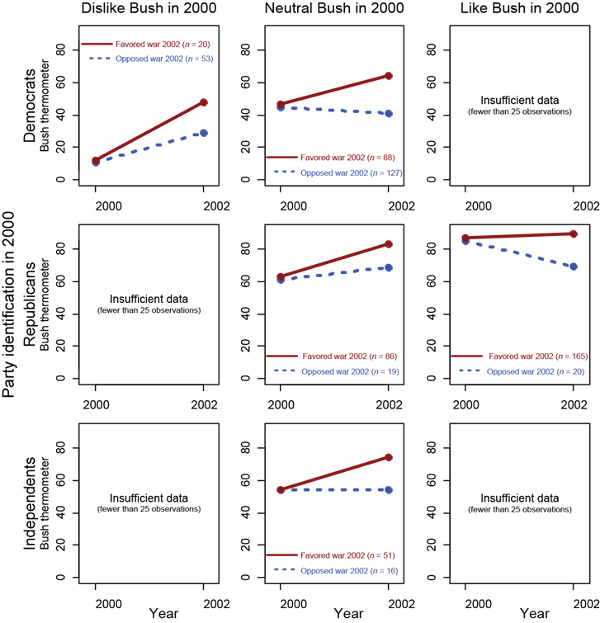

Using repeated surveys by the American National Election Studies from 2000 to 2004 allowed us to assess whether Bush was able to convince his supporters to support the Iraq War and whether support or opposition for the Iraq War affected support for Bush. Previous studies have shown support for Bush and the war are related at any given point in time, but have not been able to isolate whether Bush support causes war support, war support causes Bush support or both cause each other. Figure 1 displays the feeling thermometers of voters toward President Bush in 2000 and 2002 for various subgroups of voters.

Figure 1 – Feelings toward President Bush for Supporters and Opponents of the Iraq War, by Party and Feelings toward Bush in 2000

In the upper left panel, we show average feelings toward Bush for 73 Democrats who didn’t like Bush in 2000 (before the war was an issue). In 2000, there was essentially no difference in ratings of Bush among those who would come to support or oppose the war in 2002. By 2002, though, the 20 war supporters clearly felt more positively about Bush than the 53 war opponents. This pattern is repeated for all subgroups for which we had sufficient data: no difference in feelings toward Bush in 2000, but marked differences in 2002. These results support the view that Bush was getting rewarded and punished by voters for his pursuit of war in Iraq. This contrasts with the widespread view in the academic literature that the president leads opinion costlessly.

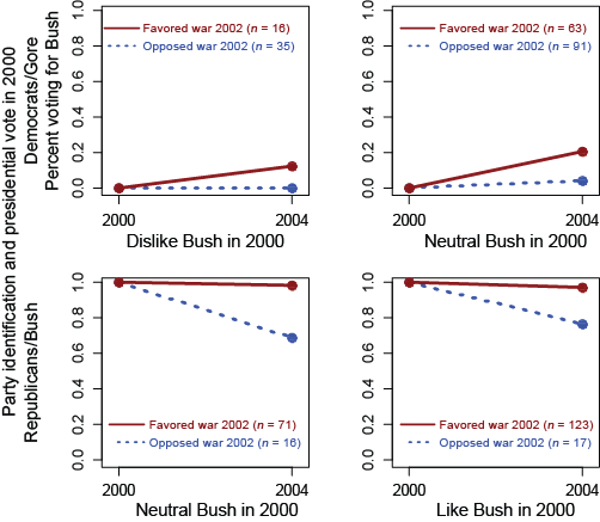

We see a similar dynamic affecting the 2004 election. Figure 2 shows votes for Bush in 2004 by supporters and opponents of the war in 2002. Among Democratic voters (the panels in the top row), Bush picked up support among war supporters; among Republicans (the panels in the bottom row), Bush lost support among war opponents.

Figure 2 – Change in vote for Bush from 2000 to 2004, by Party and Feelings toward Bush in 2000

Being able to look at multiple years of data allows us to see more changes in voter views than we would see in a snapshot from a single year. Bush picked up support among Democrats who supported the war (for an expected gain of about 6 percent of Democrats), but he also lost support among Republicans who opposed the war (for an expected loss of about 4 percent of Republicans). On net, in this analysis Bush picked up more votes than he lost given the general support for the war in 2002, but the changes in net approval rating mask movement both toward and away from Bush.

A series of statistical models confirm that the patterns we see in the figures persist even when other factors are taken into account. In addition, our earlier work has shown similar patterns when President Clinton supported “don’t ask, don’t tell” for gays in the military.

The bottom line is that presidents need to calibrate their public persuasion efforts in light of simultaneous and differential citizen responses. Sometimes presidents may simply go for approval: In his 2012 State of the Union, President Obama did not highlight his decision to send U.S. troops into Pakistan to kill Osama Bin Laden to persuade people that his policy was a good thing. That was not necessary. He was trying to convince people that he was a good president because his administration killed Osama Bin Laden. In other circumstances, Obama may have chosen policy advocacy even while recognizing that doing so would hurt his approval. In 2010, Obama predicted that his support for the Affordable Care Act would cost him 10 to 15 points in approval, but he did it anyway.

These dynamics can also lead to silence. Given that the people most likely to be policy-persuaded are already supporters, persuasion may be of limited use politically; it is not irrelevant, but having people who already like you also agree with you on an issue may be less useful if it is people who dislike the president who are preventing him from achieving his goals.

Such a dynamic may well have explained Obama’s reticence in speaking out about his health care law, especially during the 2012 election campaign. Instead of presidential leadership, we heard silence, allowing one side of the issue virtually uncontested access to the political debate.

This article is based on the paper ‘A Two-Way Street on Iraq: On the Interaction of Citizen Policy Preferences and Presidential Approval’, in American Politics Research.

Featured image credit: zeevveez (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1hDLGe5

_________________________________

Michael Bailey – Georgetown University

Michael Bailey – Georgetown University

Michael Bailey is the Colonel William J. Walsh Professor of American Government in the Department of Government and the McCourt School of Public Policy at Georgetown University. His research interests include campaign finance, relation of Supreme Court to Congress and the Executive, and interstate competition on social policy.

Clyde Wilcox – Georgetown University

Clyde Wilcox – Georgetown University

Clude Wilcox is a professor in the Government Department at Georgetown, where he has taught since 1987.He writes on a number of topics in American and Comparative politics, including religion and politics, gender politics, interest groups, public opinion and electoral behavior, campaign finance, and science fiction and politics.