Do candidates engage in dialogue with their opponents during election campaigns in the U.S? The conventional wisdom is that candidates talk past rather than to one another. In new research examining the television advertisements aired by U.S. Senate candidates, Kevin K. Banda finds that candidates do tend to partake in dialogue with their opponents and do so to a greater extent when electoral competition is higher over the course of campaigns.

Do candidates engage in dialogue with their opponents during election campaigns in the U.S? The conventional wisdom is that candidates talk past rather than to one another. In new research examining the television advertisements aired by U.S. Senate candidates, Kevin K. Banda finds that candidates do tend to partake in dialogue with their opponents and do so to a greater extent when electoral competition is higher over the course of campaigns.

Americans will head to the polls on November 8th next year to determine who will hold elected offices in the federal government. Though Election Day is well over a year away, many candidates have already begun to campaign for office. As Election Day approaches and campaigns become more intense, political pundits and members of the news media will likely bemoan the lack of discourse in American politics and claim that competing candidates talk past rather than to each other. How can Americans make well informed choices if candidates do not engage with one another’s issue priorities and positions?

In new research, I examine the degree to which the conventional wisdom about campaign dialogue reflects reality. I show that competing candidates do not ignore each other during campaigns; instead, they respond to their opponents’ discussions of issues by talking about the same issues. Candidates involved in competitive campaigns further appear to be even more responsive to their opponents relative to candidates who are contesting noncompetitive campaigns. To be more precise, candidates increase the number of television advertisements they air in which they discuss a given issue when their opponents air more ads mentioning the same issue.

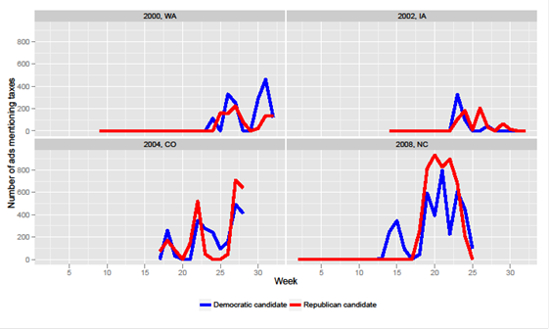

Figure 1 provides tangible examples on the issue of taxes in four U.S. Senate elections. The x-axis plots the week of an election with higher numbers indicating weeks that are closer to Election Day and the y-axis plots the number of ads in which a candidate mentioned taxes. The red line captures the number of ads in a week that mentioned taxes aired by the Republican candidate while the blue line represents that number of ads sponsored by the Democrat which also focused on taxes. If the conventional wisdom is correct, these lines would not move in concert with one another. As is clear from the plot, however, they do seem to increase and decrease at approximately the same times.

Figure 1 – Candidate Advertising on the Issue of Taxes

The relationship between candidates’ issue agendas – the issues they discuss during campaigns – is not specific to taxes. My research focuses on candidates’ issue agendas as communicated through television advertising in 93 U.S. Senate campaigns spread across 44 states and five election years (1998 – 2004 and 2008) and on 51 different political issues.

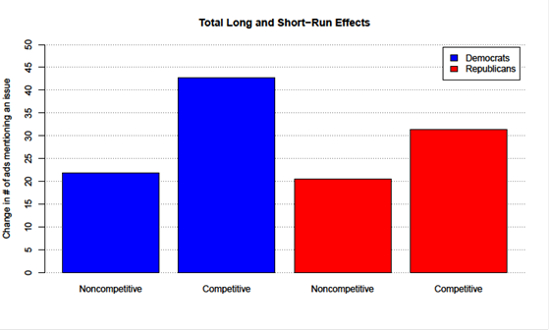

Figure 2 shows how candidates respond to changes in their opponents’ issue agendas in competitive and noncompetitive campaigns. Specifically, the figure shows the average number of additional ads that a candidate is predicted to air on some issue (taxes, education, abortion, etc.) when their opponent airs an additional 100 ads in which she discusses the same issue. When a Republican involved in a noncompetitive campaigns airs 100 additional ads about, say, health care, her Democratic opponent responds by airing about 22 additional ads of her own which also discuss health care. When the Republican does the same thing in a competitive election, the Democrat responds by airing around 42 more ads about healthcare.

Figure 2 – The Effects of Changes in Issue-based Campaign Strategies over Time

Republicans similarly respond to their Democratic opponents. In noncompetitive settings, 100 additional Democrat-sponsored ads about health care on average lead the Republican to air about 20 more health care-based ads. In a competitive campaign, this quantity increases to approximately 31. Thus, both Democrats and Republicans respond to their opponents. When their opponents devote more attention to an issue, so too do candidates themselves.

Why do candidates respond to their opponents by engaging in dialogue, and why do they do so more in more competitive campaign environments? Much of the prior research on issues and campaigns suggests that candidates should focus on the issues that advantage them the most. Some research goes so far as to suggest that candidates should never discuss the same issues as their opponents.

But there are reasons to expect candidates to focus at least some of their attention on the issues that their opponents prioritize. First, doing so may help to blunt the advantage held by their opponents on those issues by providing voters with reasons to believe that candidates may produce the kinds of policy outcomes on those issues that the voters prefer. Second, candidates may discuss the same issues as their opponents, but in a different way that advantages them. While one candidate may prefer to discuss health care policy in terms of providing equitable coverage to citizens, her opponent may wish to focus on the potential costs of implementing such a policy reform. Last, candidates may feel the need to respond to criticisms leveled against them by their opponents should they be attacked on an issue.

Given this evidence, why do so many people believe that candidates talk past each other during campaigns? One reason may be that the news media tends to focus much of its attention on particularly salient aspects of campaigns like debates. Candidates often do talk past each other during debates, but these events are not the primary means by which candidates attempt to communicate with voters; television advertisements are. Another reason may be that dialogue as observed in this research is not entirely equal; candidates air more ads discussing the issues discussed in their opponents’ advertisements when their opponent increases the number of such ads, but this response is made up of only a fraction of the total number of additional ads aired by the opponent.

This article is based on the paper “Competition and the Dynamics of Issue Convergence,” published in American Politics Research.

Featured image credit: Håkan Dahlström (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1UPZ1Bi

_________________________________

Kevin K. Banda – University of Nevada, Reno

Kevin K. Banda – University of Nevada, Reno

Kevin K. Banda is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Nevada, Reno. His research interests include campaigns, elections, public opinion, and political communication. His research has appeared in journals like Public Opinion Quarterly, American Politics Research, and State Politics & Policy Quarterly.