Many Americans have become increasingly concerned over the role of money in politics, and back more populist approaches to reducing political donations. Raymond J. La Raja and Brian F. Schaffner, authors of Campaign Finance and Political Polarization: When Purists Prevail, argue that populist approaches such as imposing low contribution limits on parties, distort the campaign finance system in ways that benefit a small group of partisan purists at the expense of the broader electorate. This in turn pushes candidates towards ideological extremes. They write that reformers should consider a more party-centered campaign finance system which would channel money to candidates through highly transparent and broadly accountable party organizations, which would then lead to less polarization.

Many Americans have become increasingly concerned over the role of money in politics, and back more populist approaches to reducing political donations. Raymond J. La Raja and Brian F. Schaffner, authors of Campaign Finance and Political Polarization: When Purists Prevail, argue that populist approaches such as imposing low contribution limits on parties, distort the campaign finance system in ways that benefit a small group of partisan purists at the expense of the broader electorate. This in turn pushes candidates towards ideological extremes. They write that reformers should consider a more party-centered campaign finance system which would channel money to candidates through highly transparent and broadly accountable party organizations, which would then lead to less polarization.

Since the 2010 Citizens United decision, there has been increasing concern over the role of money in politics. However, our new research indicates that populist approaches to curtailing money in US politics might actually be contributing to contemporary problems in the political system, including the bitter partisan stand-offs and apparent insensitivity of elected officials to the concerns of ordinary Americans. Populist approaches to campaign finance reform tend to focus on eliminating the potential for corruption by setting relatively low contributions limits to candidates and parties. But such limits rarely stop the flow of money into politics. Instead they affect the channels through which that money travels into politicians’ accounts. And increasingly, that flow pours in from highly ideological donors who tend to pull party candidates toward the extremes.

Our main argument in our new book, Campaign Finance and Political Polarization: When Purists Prevail, is that constraints on party organizations have forced candidates to rely heavily on ideological sources of funds. While party organizations tend to be highly pragmatic, preferring to support moderate candidates who reflect the views of the broader electorate, other kinds of donors – both large and small – favor highly ideological candidates. The demise of party funding relative to other sources (due to restrictive campaign finance laws and judicial decisions) has contributed to the decrease in moderate officeholders in statehouses.

Our view of party organizations runs counter to recent party “network” theorists who discount the importance of the formal party organizations. They claim instead that the party is really made up of the partisan network of allied interest groups, donors and activists who coordinate to help party candidates. While we embrace this view of the party coalition, we think organizational forms matter a great deal. The professionals who work in party organizations seek chiefly to win elections. As a by-product of this motive, they support moderate candidates who have the broadest possible appeal to voters, particularly in competitive districts. The wider partisan network, in contrast, is dominated by “purist” donors who want to elect people who agree with them on narrowly-based issue areas. Laws that restrict party organizations ineluctably shift power to the purists who seek ideological policy goals, sometimes at the expense of winning elections. Hence the subtitle of our new book: “When Purists Prevail.”

A main thrust of our argument is that party-friendly campaign finance laws should help decrease the ideological gap between the major political parties in the states and in the US Congress. Our findings bear this out.

Ideological Donors and their Impact on Legislatures

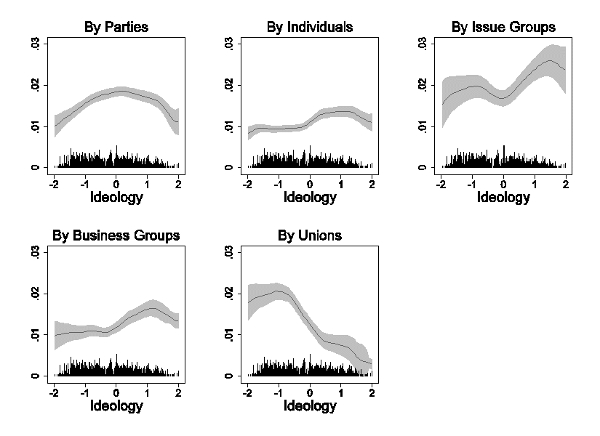

One key finding shows that different types of donors allocate their funds differently across incumbents from different ideological backgrounds. In each of the plots in Figure 1 below, the line indicates the proportion of funds from that source being contributed to incumbents at each point across the ideological spectrum. Note how party organizations concentrate their funds on moderates rather than those at the extremes. This type of distribution is unique among the actors we looked at. Issue groups give more to ideologues, particularly on the right side of the spectrum, while labor unions give overwhelmingly to liberal candidates. Individual donors and business groups tend to give across the spectrum but with a decided tilt toward conservatives (and they certainly do not favor moderates).

Figure 1 – Donations to incumbents across the ideological spectrum

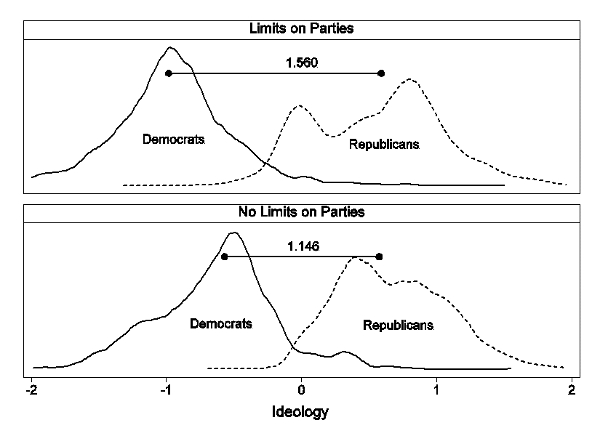

What are the consequences of these patterns? We ultimately show how campaign finance laws, which affect the flow of money, shape the ideological make-up of state legislatures. Figure 2 below shows the ideological distribution of legislators for states with contribution or fundraising limits on parties (top) and for states without either of those limits. Legislatures in unlimited states show considerably less polarization. The disparity between the two sets of states is like going from one competitive legislature that experienced considerable bipartisanship such as Indiana (which is less polarized than Congress) to another that is as polarized as Oregon (which is even more polarized than Congress). Our book illustrates other ways of assessing polarization with similar results. We conclude that states that grant parties freer access to financing tend to have less polarized legislatures. The potential implication is that such states provide more opportunities for bipartisan compromise and effective governing.

Figure 2 – Ideological distribution of legislators in states with and without campaign finance laws

Build Canals, Not Dams

Based on our results, we ultimately provide some insights for how we might approach campaign finance reform in a different way. Specifically, we argue that reformers should consider a “party-centered” campaign finance system that boosts the influence of the pragmatist wing of the party. To accomplish this strategy, reformers would have to give up on long-held assumptions about the value of imposing relatively low contribution limits on parties as a way to thwart corruption. Low contribution limits on parties distort the campaign finance system in ways that tend to benefit partisan purists at the expense of the broader electorate. These purists have the means and motive to finance candidate campaigns by mobilizing passionate factions of like-mined donors throughout the nation, and through “Super PACs”, which are financed by mega-donors giving millions.

For this reason we encourage reforms that build canals to channel the flow of money through highly transparent and broadly accountable party organizations. The strategy of erecting dams through contribution limits to hold back money does not work, and favors a relatively small group of purists. To be sure, our position may not be popular because party organizations have a tainted legacy of machine politics in the minds of many. But a vast body of research on democratic politics indicates that parties play several vital roles, including aggregating interests, guiding voter choices, and holding politicians accountable with meaningful partisan labels. It may be time for reformers to help facilitate this role for parties, rather than have the party organizations be increasingly overshadowed by other actors in the political system.

This article is based on the new book, Campaign Finance and Political Polarization by Raymond J. La Raja and Brian F. Schaffner.

Featured image credit: Public Citizen (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/21zbCdd

_________________________________

About the author

Ray La Raja – University of Massachusetts Amherst

Ray La Raja – University of Massachusetts Amherst

Ray La Raja is an associate professor in the Department of Political Science and associate director of the UMass Poll. He is author of Small Change: Money, Political Parties and Campaign Finance Reform (U. Michigan Press 2008) and editor of New Directions in American Politics (Routledge, 2013). He is founding editor of The Forum, an electronic journal of applied research in American politics.

Brian Schaffner – University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Brian Schaffner – University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Brian Schaffner is a Professor in the political science department at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and a faculty associate at the Institute for Quantitative Social Science at Harvard University. His research focuses on public opinion, campaigns and elections, political parties, and legislative politics. He is co-editor of the book Winning with Words: The Origins & Impact of Political Framing, co-author of Understanding Political Science Research Methods: The Challenge of Inference, author of Politics, Parties and Elections in America (7th edition). His research has appeared in over two-dozen refereed journal articles, including the American Political Science Review, the American Journal of Political Science, the British Journal of Political Science, Public Opinion Quarterly, Political Communication, Political Research Quarterly, Legislative Studies Quarterly, and Social Science Quarterly.

The only example you provide above disproves your theory. You state:

“The disparity between the two sets of states is like going from one competitive legislature that experienced considerable bipartisanship such as Indiana (which is less polarized than Congress) to another that is as polarized as Oregon (which is even more polarized than Congress).”

But Oregon has no limits on contributions to or expenditures by parties (or by anyone else). Indiana does have limits on contributions by corporations and unions. So your example indicates that states without limits (Oregon) have more polarization. But your theory is the opposite.