The use of racially charged imagery and messages has a long history in US politics. But how do such racial cues affect how Americans participate politically beyond holding opinions? In new research, Hans Hassell and Neil Visalvanich find that whites are less likely to participate politically when prompted by minority advocacy. They argue because of race’s influence on political motivation, political elites or interest groups could use racial priming to motivate or demotivate public political action, not just change political opinions.

The use of racially charged imagery and messages has a long history in US politics. But how do such racial cues affect how Americans participate politically beyond holding opinions? In new research, Hans Hassell and Neil Visalvanich find that whites are less likely to participate politically when prompted by minority advocacy. They argue because of race’s influence on political motivation, political elites or interest groups could use racial priming to motivate or demotivate public political action, not just change political opinions.

As America has become more diverse, how politicians and special interest groups place minorities within the political discourse has become increasingly significant. The use of racially charged imagery and racially coded messages has a long history in American electoral politics. Campaigns have long made subtle, and sometimes not so subtle, use of racial cues in order to rally supporters to certain political candidates. The ‘Willie Horton’ ad employed by then-Vice President George H.W. Bush’s presidential campaign is perhaps the most infamous example of this. More recently, the campaign for governor in Louisiana invoked terror and the specter of Islamic extremism in an attempt to tie the refugee-crisis to the Democratic candidate.

But while most research about racial cues revolves around electoral politics and political attitudes, very few studies have explored whether race priming can motivate people to participate politically. Yet voting and public opinion are not the only way citizens influence the policy process. In addition, many of the studies around racial priming have been unable to separate political preferences motivated by racial resentment from politically conservative opposition to policies tailored towards specific groups. In the era of increased racial diversity and unprecedented amounts of outside political spending on issue-based political campaigns, studying how racial cues can motivate political behavior (and not just change public opinion) becomes essential in understanding the placement of minorities in our political discourse.

In new research, we examine how racial cues affect the propensity of white Americans to participate politically. We do this by conducting an experiment that embeds racial cues in issue-based appeals for grassroots mobilization. Examining political action and race in this way allows us to look beyond voting and political attitudes and see how racial priming effects political behavior and mobilization. In addition, by utilizing a non-racialized political issue that political conservatives should be more inclined to support – the reduction of government bureaucratic regulation – we are able to distinguish racial considerations from political conservatism and gauge the effect of race on political behavior.

We recruited subjects of our experiment through Amazon Mechanical-Turk. Respondents were paid 75 cents per response and were randomly selected into three experimental scenarios. Respondents were shown an appeal to write to their member of Congress in support of the Regulatory Accountability Act. The text of this appeal varied whom the bill was meant to benefit – minorities or construction workers (the non-racialized group), with the control scenario being that no target group was mentioned. Respondents were then option to contact their member of Congress to support the bill. The experiment measured whether respondents opted to contact their representative or continue with the survey without contacting their representative. We restricted our sample to white respondents.

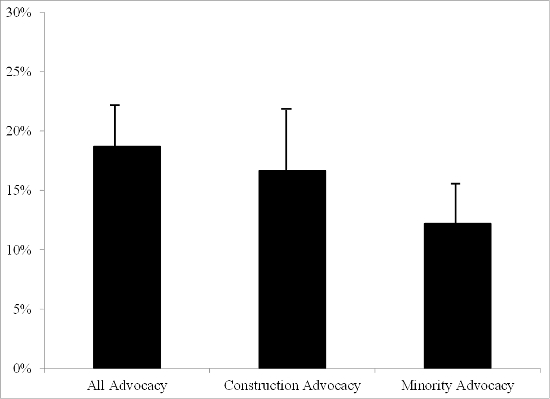

Figure 1 – Percentage of Respondents Who Wrote their Member of Congress

Note: There is a significant difference between response rate to the Minority Advocacy appeal and the Control (All Advocacy), p<.05. There is no significant difference between the Construction Advocacy appeal and the Control.

We find that, when prompted with the minority advocacy, respondents were significantly less likely to contact their member of Congress. When prompted with the construction worker cue, respondents slightly less likely to politically mobilize, but this difference is not statistically significant. These basic results offer evidence in support of the argument that, when prompted, race is very much a consideration in how whites mobilize politically.

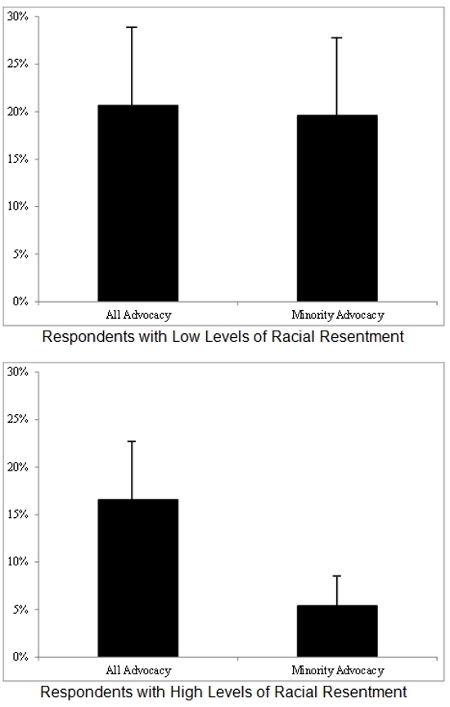

Figure 2 – Percentage of Respondents Who Wrote their Member of Congress by Levels of Racial Resentment

Note: The difference between the response rates to the two calls to action for individuals with high levels of racial resentment is significant at p<.01. There is no significant difference between the response rates of individuals with low levels of racial resentment.

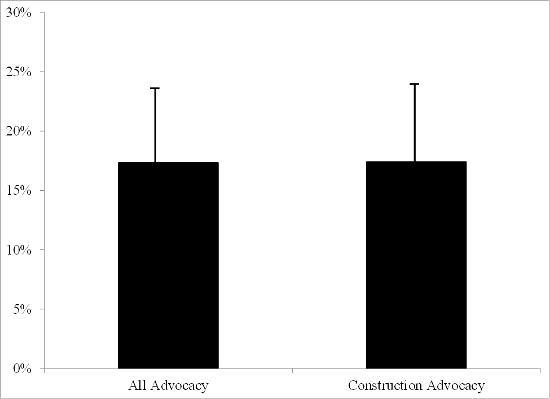

Figure 3 – Percentage of Respondents with High Levels of Racial Resentment Who Wrote their Member of Congress

Note: There is no significant difference between the response rates to the two calls to action for individuals with high levels of racial resentment to the treatment (Construction Advocacy) and the control (All Advocacy).

A closer examination of the results reveals that most of the bias against the minority advocacy appeal comes from segments of the population with racially resentful beliefs. Respondents with low levels of racial resentment were just as likely to contact their member of Congress when presented with the control appeal when compared to the minority appeal. On the other hand, respondents with high levels of racial resentment were significantly less likely to respond when presented with the minority appeal. On the other hand, when presented with the construction worker appeal, respondents with high levels of racial resentment were no less likely to respond to this specialized group appeal than the control scenario, providing evidence that race is the motivating factor as opposed to opposition to policies tailored towards specific groups.

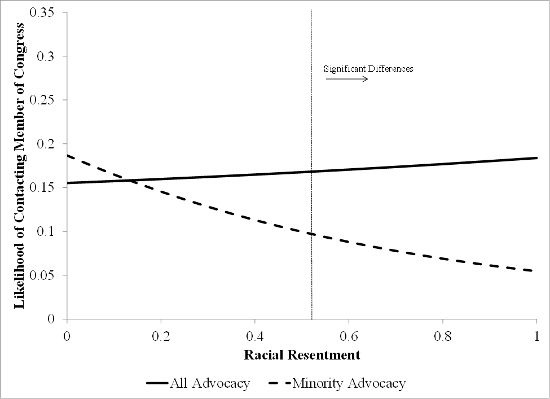

Figure 4 – Likelihood of Respondent Contacting Member of Congress

Our study shows that race remains an important consideration in motivating white voters to act, or in this case, decline to act politically. While the nature of this experiment finds that race can be a demotivating factor in political mobilization, one can extrapolate from these results that race could also potentially be a mobilizing factor as well. If racial attitudes have such a significant effect on political engagement, it is feasible that political elites or interest groups could use racial priming, either intentionally or unintentionally, to motivate or demotivate political action. In addition, as America becomes an increasingly diverse country, race will also likely become a more prevalent influence on our political and social identities. Given the changing racial dynamics in America, the pervasive effect of race on political action may become even more significant over time.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Call to (In)Action: The Effects of Racial Priming on Grassroots Mobilization’ in Political Behavior.

Featured image credit: Fibonacci Blue (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1Qs09IP

_________________________________

About the authors

Hans J.G. Hassell – Cornell College

Hans J.G. Hassell – Cornell College

Hans J.G. Hassell is an Assistant Professor of Politics at Cornell College. His research focuses on political parties, elections and political behavior, and Congress. He is also interested in how the contextual political environment, especially aspects such as race, ethnicity, and immigration, affect political behaviors. His work has appeared in the Journal of Politics, the American Journal of Political Science, and Political Behavior. Hans’s website: http://people.cornellcollege.edu/hhassell/

Neil Visalvanich – Durham University

Neil Visalvanich – Durham University

Neil Visalvanich lecturer (tenure-track professor) in the School of Government and International Affairs at Durham University, United Kingdom and an associate of the Centre for Institutions and Political Behaviour. His research focuses on the race and ethnicity in comparative and American politics. His work has appeared in Political Science Research and Methods and Political Behavior. Neil’s website: http://www.neilvisal.com/