Partisan polarization has perhaps been most common term used to describe American politics in recent years. In new research, Jesse H. Rhodes and Zachary Albert investigate how partisanship has manifested in presidential campaigns over the past six decades. They find that – contrary to the impression created by contemporary public discussion and media coverage – explicit partisanship has declined dramatically as a feature of presidential campaigns, largely due to the abandonment of partisan rhetoric by Democratic presidential candidates. They argue that Democratic candidates have avoided partisan appeals in their public rhetoric in order to reach out to moderate voters alienated by corrosive partisanship.

Partisan polarization has perhaps been most common term used to describe American politics in recent years. In new research, Jesse H. Rhodes and Zachary Albert investigate how partisanship has manifested in presidential campaigns over the past six decades. They find that – contrary to the impression created by contemporary public discussion and media coverage – explicit partisanship has declined dramatically as a feature of presidential campaigns, largely due to the abandonment of partisan rhetoric by Democratic presidential candidates. They argue that Democratic candidates have avoided partisan appeals in their public rhetoric in order to reach out to moderate voters alienated by corrosive partisanship.

From the halls of Congress to the opinions of ordinary citizens, partisan polarization is on the rise in American politics. Scholars are increasingly interested in how and why partisanship has become such a prominent feature of American politics, as well as in the consequences of this development for American democracy. Yet – despite the centrality of the presidency in the American political system – research on the evolution and consequences of partisanship largely overlooks presidential politics and campaigns.

What role has partisanship played in presidential campaigns in recent decades? Have presidential campaigns (like other aspects of American politics) become more partisan over time? Or has presidential candidate rhetoric about parties exhibited some other pattern? And what best explains over-time trends in presidential candidate partisanship?

Our new research shows that – contrary to the impression created by contemporary public discussion and media coverage – explicit partisanship has declined dramatically as a feature of presidential campaigns from 1952 to 2012. This is primarily due to the abandonment of partisan appeals by Democratic presidential candidates; Republican candidates have generally eschewed partisan rhetoric throughout the entire period. Moreover, our results suggest that Democrats have abandoned partisan appeals largely for strategic reasons. Specifically, Democratic candidates have gradually adopted more conciliatory campaign language to reach out to moderate and independent voters disaffected by partisan polarization.

Our research relied on a content analysis of every explicit reference (more than 8,000 in all!) to one or both political parties by both Democratic and Republican candidates in hundreds of general election stump speeches between 1952 and 2012. For our analysis, we coded a random sample of statements, assessing whether each statement was characterized by a positive or negative overall tone toward the mentioned party or, alternatively, whether it advocated the transcendence of partisanship. (We also included a category called “not about the parties” to deal with statements that did not really include references to one party or the other.)

Thus, for example, statements in which the presidential candidate touted the party’s legislative record or lauded its candidates were coded as positive; while statements in which the candidate criticized the party’s proposals or mocked its candidates were coded as negative. Importantly, our coding procedures allowed for the possibility that presidential candidates might make negative statements about their own party or positive references to the opposition.

To deal with the huge number of statements gathered for our analysis, we used a powerful automated content analysis algorithm to learn our coding rules and apply them to uncoded data. We made extensive validation checks to ensure that the algorithm accurately replicated the coding we did by hand.

Finally, for each presidential candidate we recreated important categories from the coded data. We defined partisan rhetoric as statements involving either positive references to the candidate’s party or negative references to the opposition; cross-partisan rhetoric as statements comprising negative references to the candidate’s party and positive references to the opposition; and bipartisan rhetoric as statements including references to both parties and entailing criticism of partisanship or appeals for bipartisan unity.

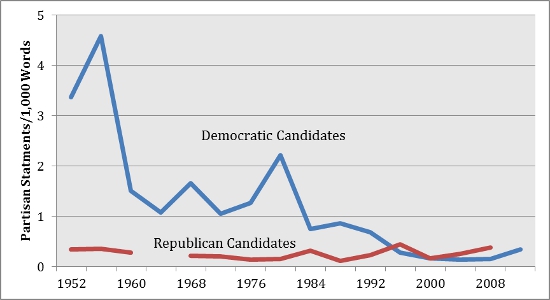

We focused on examining (and explaining) trends in partisan rhetoric. Strikingly, as Figure 1 shows, we found that presidential campaigns have become much less partisan over time – though this is primarily due to the gradual abandonment of explicit partisan appeals by Democratic presidential candidates. While Democratic candidates employed partisan appeals quite frequently on the campaign trail in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, they increasingly forsook this rhetoric in subsequent decades.

In contrast, Republican candidates rarely employed partisan appeals in general campaign stump speeches – and there has been very little deviation from this pattern over time.

Figure 1 – Frequency of Partisan Statements by Presidential Candidates (per 1,000 words)

Note: Data for the chart are drawn from presidential candidate stump speeches, archived in the Annenberg/Pew Archive of Presidential Election Discourse and the American Presidency Project (americanpresidency.org).

Our analysis evaluated a variety of potential explanations for the decline of Democratic candidate partisanship from the political science literature on campaign appeals, including the competitiveness of the campaign, incumbency, party control of Congress, and the strength of partisan identification in the electorate. These explanations provided limited insight on the gradual disappearance of partisan rhetoric in Democratic presidential campaigns.

As an alternative explanation, we proposed that Democratic candidates’ decreasing use of partisan appeals on the campaign trail reflected a strategic adjustment to a changing campaign environment in which partisanship has increasingly become a political liability. During the 1950s and 1960s, the Democratic Party brand was quite popular, and the party was ascendant in national politics. This made partisanship a powerful rhetorical tool in the arsenal of Democratic presidential candidates. Moreover, because partisan polarization was modest Democratic candidates could employ partisan appeals without the risk of alienating moderate voters.

However, the declining popularity of the Democratic brand from the 1970s onward – especially in the South – made partisan appeals a less useful campaign strategy for Democratic presidential candidates in the following decades. Furthermore, as many moderate voters gradually became disgusted with rising partisan acrimony, Democratic candidates faced increasing pressure to adjust their public rhetoric so as to project an appealing image of unity and bipartisan conciliation capable of attracting disaffected voters.

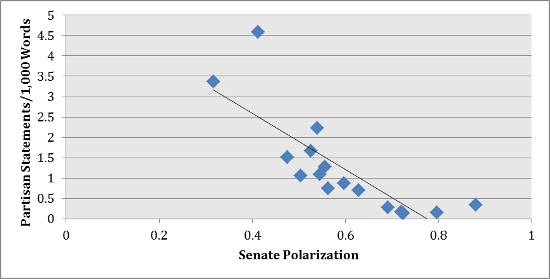

We provide statistical evidence for this argument by showing that Democratic rhetorical partisanship is strongly – and inversely – related to partisan polarization in Congress, even controlling for all of the other factors mentioned above. In other words, the more polarized Congress has become, the less Democratic candidates have featured partisan appeals on the campaign trail. Figure 2 below – which plots the frequency of partisan statements by Democratic candidates against the level of partisan polarization in the Senate – provides a nice illustration of this pattern.

Figure 2 – Scatterplot of Frequency of Democratic Partisan Statements and Senate Polarization, Democratic Candidates Only, 1952-2012

We also sought to explain Republicans’ consistent preference for conciliatory rhetoric. We argue that partisan appeals have never been an especially good fit for Republican candidates seeking the presidency. In the 1950s and 1960s the Republican Party brand was not especially strong, discouraging the party’s presidential candidates from featuring partisan appeals. Afterward, rising partisan polarization – and increasing frustration among political moderates with polarized politics – dissuaded Republican candidates from embracing partisan appeals, despite dramatic improvement in the party’s fortunes.

To be clear, our argument is not that presidential candidates have genuinely embraced a more conciliatory politics. Rather, presidential candidates have learned how to present a more bipartisan public image while at the same time advancing partisan goals out of the public spotlight. Indeed, presidential candidates have used relatively discrete methods – including fundraising, organization-building, grassroots mobilization, and candidate recruitment – to strengthen their parties behind the scenes.

In truth, presidential candidates don’t even need to feature partisan appeals in their own rhetoric in order for such messages to get across to their core supporters, because partisan television stations, newspapers, and websites can convey these communications for them. In a very real sense, the fragmentation of the media and the proliferation of alternative news sources have further encouraged (and facilitated) candidates’ abandonment of explicit partisan rhetoric.

Our research predicts that the 2016 presidential campaign should be marked by the limited use of explicit partisan appeals by both Democratic and Republican candidates. Far from indicating the reemergence of bipartisan conciliation, however, this would provide further confirmation of the candidates’ strategic efforts to present themselves in the most appealing light in an era of extreme (and broadly unpopular) partisan polarization. Indeed, we fully expect candidates from both parties to continue – and even intensify – partisan activities out of the limelight.

This article is based on Rhodes’ and Albert’s “The Transformation of Partisan Rhetoric in American Presidential Campaigns, 1952-2012,” published in Party Politics.

Featured image credit: PBS NewsHour (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1ZlAZwX

_________________________________

Jesse H. Rhodes – University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Jesse H. Rhodes – University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Jesse H. Rhodes is an associate professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. He is the author of An Education in Politics: The Origins and Evolution of No Child Left Behind (Cornell University Press, 2012), as well as of articles in Perspectives on Politics, Party Politics, Presidential Studies Quarterly, Publius, TransAtlantica, and other journals.

Zachary Albert – University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Zachary Albert – University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Zachary Albert is a graduate student in the Department of Political Science at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.