The past year has seen major decisions by the Supreme Court on gay marriage and Obamacare. But what influences the coalitions of opinion in Supreme Court decisions? In new research that examines nearly 30,000 choices by Supreme Court justices over 40 years, Andrew J. O’Geen and Christopher M. Parker find that when a decision’s initial majority is small, justices are much less likely to write separate opinions in order to stabilize the shaky majority.

The past year has seen major decisions by the Supreme Court on gay marriage and Obamacare. But what influences the coalitions of opinion in Supreme Court decisions? In new research that examines nearly 30,000 choices by Supreme Court justices over 40 years, Andrew J. O’Geen and Christopher M. Parker find that when a decision’s initial majority is small, justices are much less likely to write separate opinions in order to stabilize the shaky majority.

In a recent interview, US Supreme Court justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg explained that a prudent choice for a justice in the majority is to occasionally overlook one’s preferred position in favor of the clarity provided by a unified majority opinion. Common sense and empirical research support Justice Ginsburg’s impression, showing that cases with fractured majorities are less likely to be viewed positively by lower courts. However, justices in the majority also face strong incentives to engage in self-interested behavior by writing separate opinions. If it is true that unified majorities are a collectively beneficial outcome, how can justices in the majority achieve the level of cooperation necessary to reach this goal? Our new research highlights the conditions under which cooperation on the US Supreme Court is more likely.

The achievement of a collective goal by any group depends upon cooperation. If incentives push individuals too far toward self-interested behavior, collective action is difficult or impossible. Similarly, the pull of the benefits of cooperation depend on whether and to what degree the group can provide the outcomes that satisfy the individuals’ preferences. Therefore, characteristics of individuals and characteristics of groups are both important factors influencing cooperation.

The US Supreme Court represents an ideal testing ground for attempts to understand how self-interested actors might overcome their selfish instincts and cooperate to produce a mutually beneficial result. Self-interested justices must consider not only their personal preferences when deciding on a position but, because a majority is needed to establish precedent on the Court, they must also consider the integrity of the coalition and the group. Fragile coalitions may falter under the weight of disagreements whereas more stable coalitions may endure even after losing a member or two.

One place where these types of competing motivations are particularly active is in the Court’s opinion writing process. A justice in the initial majority can choose to join the majority silently or choose to write a separate concurring opinion articulating their preferred position more clearly. When deciding whether to author a separate opinion, justices face several considerations. First is a desire to express their preferred interpretation of specific legal principles and potentially shape the current and future state of the law on a particular issue. Second is a need to articulate clear, workable rules that offer guidance to those tasked with implementing the Court’s decisions.

To better understand how these competing forces work to shape the behavior of the justices, we analyzed over 29,000 individual choices by justices from more than 4,500 US Supreme Court cases over 40 years. Our results reveal some interesting trends in the justices’ decisions to join the majority or write a special concurring opinion. A justice’s choice to write separately is driven by the preferences of the justice, specific characteristics of the case, and by strategic decisions about relationships with their colleagues on the Court.

In politically or legally important cases, a justice in the majority is significantly more likely to write separately. It seems that justices prefer individual gain to long-term coalition building in these important cases. However, when the initial majority is small, dissolution of the coalition from defection is much more likely. In these cases, our data show justices are significantly less likely to write separately when part of a minimum winning majority than in cases with larger coalitions.

We also find that ideological considerations are important to this choice. As one might expect, the further a justice is ideologically from the opinion author, the more likely they are to write a separate opinion. Interestingly, group considerations moderate this effect. In cases where the majority is closely clustered ideologically, the loss of one member is less likely to dissolve the coalition. However, ideologically diverse coalitions are likely to be much more tenuous. Here we might expect defection to negatively impact the stability of the group.

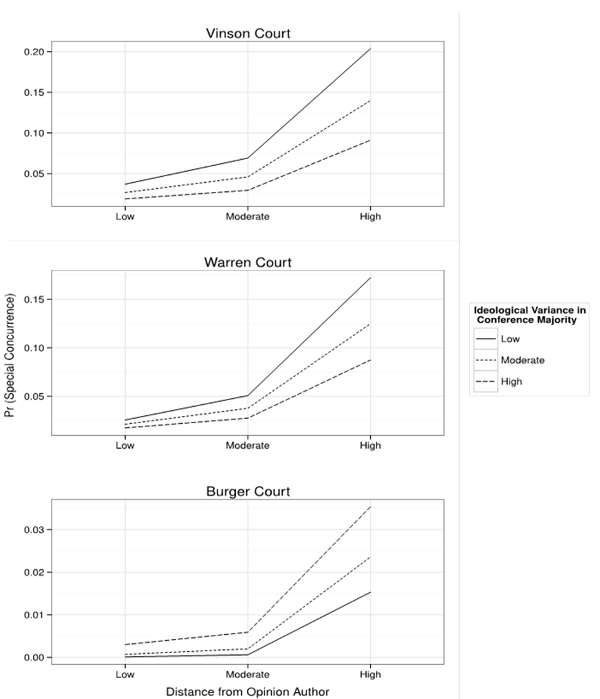

Figure 1 shows this conditional effect of ideology across the tenure of three Chief Justices. The y-axis represents the probability that a justice in the majority will write a separate concurring opinion. As is clear from the figure, this probability is increasing with distance from the opinion author (the x-axis).

Figure 1 – The Conditional effect of ideology on Supreme Court opinions

The conditional effect can be seen by the steepness of the three lines. The steeper the line, the stronger the effect of individual ideology. In the Vinson and Warren Court eras, the effect of individual ideology is significantly weaker in diverse coalitions. So, justices act selfishly when the coalition is relatively stable, but are more willing to suppress their desire to realize their individual preferences when it means stabilizing a shaky majority.

The same pattern does not hold however during the Burger Court years, 1969-1986. This was an important period of transition on the Court, when the relatively liberal justices of the Warren era were replaced by more conservative Nixon, Ford, and Reagan appointees. In these years, the average ideological diversity of majority coalitions is much higher than in previous eras. This is reflected in much lower instances of concurring behavior overall.

The US Supreme Court straddles the line between law and politics and the justices are interpreting the law and shaping public policy in a setting that is unique among actors in American politics. This position gives the justices considerable leeway to act in accordance with their individual preferences. However, if the members in the majority cannot remain relatively cohesive, there is the possibility that the opposing coalition of justices may be able to craft a new opinion that may gain a majority and set an alternative precedent that is not as preferred. In situations where the majority coalition is likely to be fragile, justices seem to be more willing to compromise and join a majority opinion even if it does not set a precedent at their most preferred position. Declining the opportunity to write separately in these cases can prevent the majority coalition from dissolving and also help strengthen the precedent’s vitality in the long term.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Strategic Cooperation: Modeling Concurring Behavior on the U.S. Supreme Court’, in American Politics Research.

Featured image: Supreme Court Chamber Credit: Phil Roeder (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1RCXfRJ

_________________________________

Andrew J. O’Geen – Davidson College

Andrew J. O’Geen – Davidson College

Andrew J. O’Geen is MacArthur Assistant Professor at Davidson College. His research focuses on American political institutions with an emphasis on law and courts. His current research investigates how institutions interact to shape the US Supreme Court’s agenda.

Christopher M. Parker – Centenary College of Louisiana

Christopher M. Parker – Centenary College of Louisiana

Christopher M. Parker is an assistant professor of political science at Centenary College of Louisiana. His current research focuses on judicial politics and decision making on the United States Supreme Court and state appellate courts.