With the general election season now upon us, both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump are considering who to pick to be their Vice President. In new research, Boris Heersink and Brenton D. Peterson argue that to help them win the presidency, the candidates should consider someone from a swing state. Why? They find that, in contrast to previous studies, a running mate can increase a presidential ticket’s support by nearly 3 percent in a Vice President’s home state, something which could have swung four elections since 1960.

With the general election season now upon us, both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump are considering who to pick to be their Vice President. In new research, Boris Heersink and Brenton D. Peterson argue that to help them win the presidency, the candidates should consider someone from a swing state. Why? They find that, in contrast to previous studies, a running mate can increase a presidential ticket’s support by nearly 3 percent in a Vice President’s home state, something which could have swung four elections since 1960.

With Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump all but assured of their party’s presidential nominations, both candidates are now considering an important decision: selecting their running mate. Trump and Clinton may be wondering whether these running mates are likely to provide them with any electoral benefits – specifically in swing states. That is, is there any reason to believe vice-presidential candidates add votes for their ticket in their home states? Contrary to previous findings, in a recent study we show that running mates can indeed provide considerable assistance in their home states, adding nearly three percentage points to their ticket’s performance there.

These results are in contrast to existing political science research, which has consistently found that this benefit – the vice-presidential home state advantage (HSA) – is either nonexistent or so small that it is basically irrelevant. According to these studies, the average VP HSA is less than 1 percentage point. Crucially, these studies have concluded that the advantage is bigger in smaller states, but since these states also have fewer electoral votes, running mates remain unlikely to influence the general election outcome as a whole.

Our results are dramatically different: we find that running mates – on average – add 2.67 percentage points to their ticket’s performance in their home states. We also find that these results are robust in swing-states, states with a high number of electoral votes, and states which combine both. This means that a running mate from an important swing-state could bring in enough votes to win the state – and the general election.

Why do our results differ so much from the traditional findings? Scholars have typically measured the HSA by comparing election results in the home state of the running mate to the national vote share. To account for pre-existing differences between home state and national electoral performance, these scholars incorporate the average national and state vote share over the previous five elections. The difference between home state and national vote share in the election of interest, compared to that over the previous five elections, is assumed to measure the extent of a running mate’s impact in their home state.

We argue that there are fundamental problems in relying on this approach to measure the vice-presidential HSA. First, national party performance is not always a great predictor of state-level performance. While states may vote similarly to others in their region, they frequently deviate considerably from the average vote across all 50 states. Second, and even more concerning, we found that running mates are – on average – selected from states in which the party’s performance has dropped in recent elections. Because performance over the previous five elections should account for party strength in a state, this downward trend results in an overestimate of ‘expected’ vote share.

A great example is Lyndon Johnson’s home state advantage in Texas in the 1960 election. Using the traditional measure, scholars argue that LBJ had a negative home state advantage of 14.72 points. That is, we would need to believe that John F. Kennedy would have won nearly fifteen additional points in Texas had he not selected Johnson. This is highly unlikely – if only because Johnson himself was also on the ballot for his senate seat in 1960 and won more votes than the JFK-LBJ ticket did. Instead, LBJ is the victim of the inherent flaws in the measurement. Democrats routinely won 80 percent of the vote in Texas, or more, until the late 1940s. The traditional measure compares the Democrats’ performance in 1960 to their performances from 1940 to 1956. But by 1960, Texas had become much more competitive electorally. As a result, the expected result for what the Democrats’ vote in 1960 should have been is much higher than is realistic.

In contrast to the traditional formula, we use the synthetic control method, which uses averages of several other states that are similar to the vice-presidential candidate’s home state. In doing so, we create a “synthetic” version of that state which closely approximates the home state except that the running mate is not from this version of the state. This means that downward trends like those that plague measures of LBJ’s home state advantage do not impact our measure, because we are able to select a set of states with trends to match.

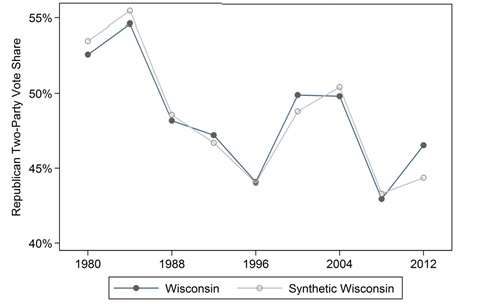

For instance, to estimate the impact of Mitt Romney’s 2012 Vice Presidential pick, Paul Ryan’s on the Republicans’ performance in Wisconsin in 2012, we created a “synthetic Wisconsin” composed of Iowa, Mississippi, Hawaii, Maryland and West Virginia. Separately, none of these states provide a good match with Wisconsin, but, once combined, the Republican vote share in “synthetic Wisconsin” looks very similar to the actual results in Wisconsin from 1980 to 2008.

As Figure 1 shows, “synthetic Wisconsin” follows real Wisconsin closely until 2012, when Paul Ryan is on the ticket. The gap between real and synthetic Wisconsin in 2012 – 2.53 percentage points – is our estimate of Ryan’s home state advantage.

Figure 1 – Paul Ryan’s VP home state advantage, 2012

We find that vice-presidential candidates add an average of 2.67 points to their parties’ performance in their home states. This finding is not limited to “safe” states, nor is it limited to a particular historical time period. And the effect is large enough that it could have altered the outcome in four presidential elections since 1960. Specifically, for Republicans in 1960 and 1976, and Democrats in 2000 and 2004, the selection of a vice-presidential candidate from a key swing state could have swung the election.

What does this mean for the selection of a running mate for Clinton and Trump? In a close election, candidates can benefit from selecting a vice-presidential candidate from a swing state for two reasons. First, if the election is very close – like in 2000 or 2004 – a swing state running mate could flip the deciding state and make the difference between winning or losing the White House. But even if an election hinges on several swing states, selecting a running mate from one could safeguard this state for the campaign, allowing it to focus money and resources on other states instead. Therefore, if the Trump or Clinton campaigns expect the election to be at all competitive, selecting a running mate from a swing-state – think Tim Kaine (from Virginia) on the Democratic side, or Scott Walker (from Wisconsin) on the Republican side – could be an easy way to improve their probability of winning the White House in November.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Measuring the Vice-Presidential Home State Advantage With Synthetic Controls’, in American Politics Research.

Featured image credit: Bryan Bliss (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/28Jw0Tv

______________________

Boris Heersink – University of Virginia

Boris Heersink – University of Virginia

Boris Heersink is a PhD candidate in the Department of Politics at the University of Virginia where he studies American politics and a national fellow at the Miller Center. His research focuses on the role of national party organizations in American politics, the influence of strategic choices and individual events on elections, and the development of party politics in the American South.

Brenton D. Peterson – University of Virginia

Brenton D. Peterson – University of Virginia

Brenton D. Peterson is a PhD candidate in the Department of Politics at the University of Virginia, where he studies African politics, and a Research Affiliate at Strathmore University in Nairobi. His research primarily focuses on ethnic politics and the formation of ethnic identities in East Africa; he is also interested in quantitative methods for causal inference and developing experimental measures of social attitudes.