For every successful Olympic bid over the last 16 years, there have been more than six unsuccessful ones. But when Olympic bids fail, what happens next in the bidding city? John Lauermann writes that such bids can stimulate urban development, even if they do not secure the Olympic Games. Not only can they push forward long term development agendas, he says, their plans can also be recycled into future urban redevelopment initiatives.

For every successful Olympic bid over the last 16 years, there have been more than six unsuccessful ones. But when Olympic bids fail, what happens next in the bidding city? John Lauermann writes that such bids can stimulate urban development, even if they do not secure the Olympic Games. Not only can they push forward long term development agendas, he says, their plans can also be recycled into future urban redevelopment initiatives.

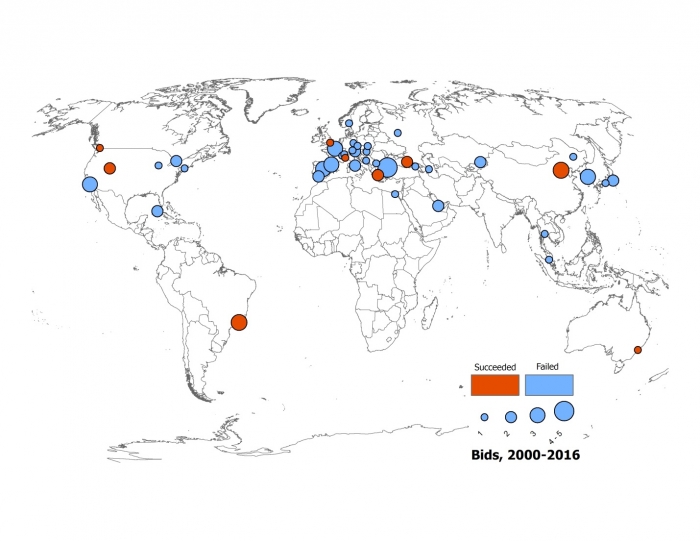

The Olympics and other sports mega-events are often promoted as a ‘catalyst’ for urban development: a temporary planning project that will yield long term benefits for a city. There is much evidence for and against this catalyst effect in cities that have previously hosted the Games. But the vast majority of Olympic planning actually happens elsewhere, in cities that lose their bids to host the Games. As Figure 1 shows, since 2000 there have been eight Summer and Winter Olympic host cities; during that same period there were 52 bids from 39 different cities. These failed bids represent a significant and risky investment by cities around the world. Bidders budgeted an average of $31.6 million to fund just the bidding itself, and among current bidding cities – for the 2024 Games – Budapest plans to spend $58.5 million Los Angeles $40-55 million, Rome $35.1 million, and Paris €60 million. But there has been relatively little research on the impact of all this failed bidding on urban planning and governance. The majority of Olympic planning projects fail: what happens next? Is any value recouped from the investment?

Figure 1 – Olympic bid cities, 2000-2016

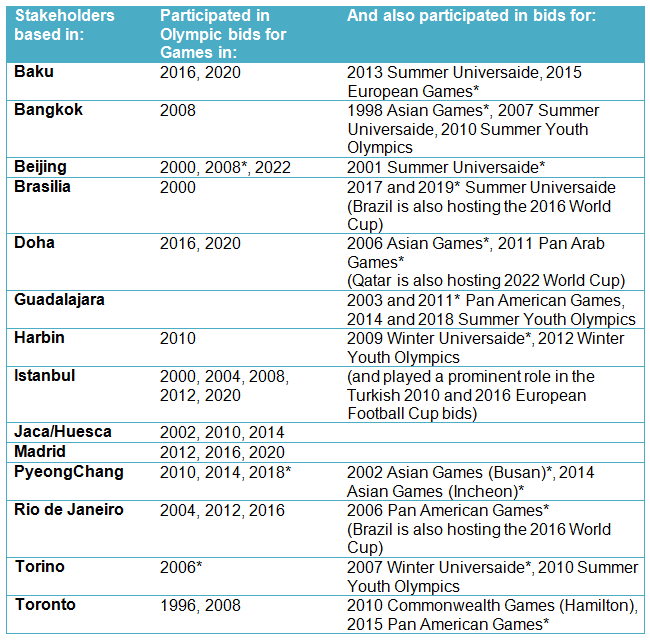

My research on the Olympic planning industry has found that Olympic bids can facilitate urban development after failure, for two reasons. First, they push forward elements of longer term development agendas. City leaders often use bids as part of a ‘mega-event strategy’ to draw global attention to promote local projects. Bids are large scale urban policymaking exercises which can build political coalitions (e.g. as bid corporations gather guarantees of support from public and private sponsors in dozens of categories), open up new financing channels (e.g. American bids in New York and Chicago developed new tax increment financing districts), and provide city leaders with access to an extensive global network of planning expertise (e.g. travelling networks of ‘Olympic nomads’ who move from city to city consulting on bids). Second and as a result, when a bid fails plans proposed in it are often recycled into future urban policy initiatives. As Table 1 shows, many cities bid multiple times on the Olympics and smaller mega-events (e.g. Commonwealth or Pan American Games), recycling designs and refining plans along the way. Some high frequency bidders have been particularly active on this front, bidding on three or more major sports events within a ten-year window.

Table 1 – Olympic bids, 2000-2016

Note: Bids date 1991-2013 for events 1996-2022; * = won the bid/secured the hosting contract. ‘Participation’ in a bid means financing the bid corporation, guaranteeing financial shortfalls, or investing in real estate projects.

New York City’s failed bid for the 2012 Olympics illustrates the process. The city has a long history of using mega-events to catalyze land investment extending back to the city’s infamous modernist planner Robert Moses, who organized two World’s Fairs to redevelop a dump in Queens and to lobby for suburban highway funding. In the early 2000s a coalition of real estate interests, Wall Street executives, and City Hall launched a bid for the 2012 Summer Games. That event went to London instead, but after the New York bid failed many of the projects it proposed moved forward anyway.

The Olympic bid master plan reflected a much longer term planning agenda: it was based on a series of brownfield and greyfield redevelopment projects, many of which had been zoned for redevelopment in the 1970s and had stalled for political or financial reasons. The bid was an opportunity for the city to start or prop up several municipal redevelopment corporations, which continued on after the bid failed using similar site designs and plans: the athletes village became a housing complex, the Olympic park became a mixed-used real estate project with similar green space design, and an arena became an arena. This post-bid redevelopment allowed the bid planners to claim that New York was able to succeed through failure. The city was able to use the bid as an urban planning catalyst, while avoiding the risks and costs that come along with actually building venues to Olympic specifications. This counterintuitive idea was widely repeated by the original bidders – including former mayor Michael Bloomberg – as various pieces of the Olympic master plan were recycled into new but similar projects.

The broader implication is that some Olympic bidders may not intend to win at all, but rather to use the bidding process to achieve other objectives. The timing of Olympic planning can distort communities’ decision-making: bids are finalized 7-10 years in advance and bidders have historically underestimated the final cost of their projects by an average of 127 percent. Thus citizens and city leaders must deliberate them on long time horizons with imperfect information. This uncertainly is amplified further when bidders have agendas that may have little relationship to actually hosting the Games. These compounding uncertainties are fueling concerns by anti-Olympic activists. They are increasingly mobilizing early in the planning process for this reason, and have successfully defeated a number of 2022 Winter Games bids and 2024 Summer Games bids in Boston and Hamburg.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Temporary projects, durable outcomes: Urban development through failed Olympic bids?’, in Urban Studies.

Featured image credit: Eva (Flickr, CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/29TM3wR

_________________________________

John Lauermann – Texas A&M University

John Lauermann – Texas A&M University

John Lauermann is a visiting assistant professor of Geography at Texas A&M University. His research examines how transnational real estate industries influence urban land investment. A book on Failed Olympic Bids and the Transformation of Urban Space is forthcoming with Palgrave Macmillan (co-written with Robert Oliver).