In the past two weeks political commentators have been gripped with convention fever, as the Republican and Democratic parties met to choose their respective nominees for this year’s presidential election. Lindsay Hoffman comments that both conventions were marked not by chaos or violent protests – as many had predicted – but by their awkwardness. Despite the wall to wall coverage, with the presidential election campaign about to enter high gear, she writes that the conventions will soon be a distant memory for the public.

In the past two weeks political commentators have been gripped with convention fever, as the Republican and Democratic parties met to choose their respective nominees for this year’s presidential election. Lindsay Hoffman comments that both conventions were marked not by chaos or violent protests – as many had predicted – but by their awkwardness. Despite the wall to wall coverage, with the presidential election campaign about to enter high gear, she writes that the conventions will soon be a distant memory for the public.

They’re over. The conventions, which everyone has been talking about for two weeks, are over. But what role have they really played in this long selection process for the President? I had the unique opportunity to attend and observe the theatrics of the Democratic National Convention in Charlotte, North Carolina in 2012. As a professor who teaches about these spectacles and researches media coverage and framing of these closely watched events, I couldn’t pass up the chance to see it for real and in person. What did I find? A. Huge. Party. What goes on in the Convention Hall is really just one part of what is going on during the conventions. It’s also about the protests, the speeches, the vendors, the non-profits handing out pamphlets, and all the celebrities! I wrote about the euphoria and contagious energy for the Huffington Post in 2012.

So how does this year differ? There were still the theatrics, the balloons, the speakers. But what made each convention notably different was the dissention in the ranks – and the quick tamping down of that dissent. Remember that nominating conventions weren’t always this way. Let’s go back a bit further than 2012. 1789, specifically. In the first two elections in the United States, the nominee (George Washington) was selected by the Electoral College. Parties—and partisan politics—became the name of the game by 1796, and nominees were selected by caucus. But in 1831, a third party (the Anti-Masonic Party), had no Congressmen, and so couldn’t caucus. They called a national meeting of party members and supporters to select their nominee, and the nominating convention was born. For nearly a century, party bosses wheeled and dealed to influence delegates in selecting the nominee (think of those “smoke-filled back rooms”).

It wasn’t until 1968, at the chaotic Democratic National Convention in Chicago, that reforms established delegate selection to be open, and that delegates would represent the proportion of their population in each state. Primaries became the path to nomination. These changes came as a result of disdain for the power of political bosses and the desire for more open selection of nominees. The Republican Party followed by adopting primaries in 1972, and the primary system was born. While there were ripples in 1976—when Ronald Reagan nearly obtained the needed delegates to take the nomination from incumbent president Gerald Ford—and 1980—when Ted Kennedy sought to release delegates from incumbent Jimmy Carter—the conventions over the past 4 decades have been relatively predictable. The nominee is often known far in advance, partly because of the increase in front-loading the primaries, and the convention is a rally-around-the-nominee event, loaded with party loyalty and lots, and lots, of balloons. (Okay, there were a couple times that the balloons didn’t fall properly, creating probably the most buzz around those conventions.)

That’s what I saw in 2012. This year, although I wasn’t able to attend either party’s convention, the dissention was audible, even to a television audience. It seemed at times less like a party and more like an awkward blind date, where the person who showed up wasn’t quite who you expected. First there were the supporters of Texas Senator Ted Cruz who attempted to change convention rules so that delegates weren’t beholden to primary results supporting Donald Trump. That failed, quickly, on Day 1 in Cleveland, and he was summarily booed when he didn’t endorse Trump in his convention speech. In Philadelphia, we saw Bernie Sanders’s supporters booing, walking out, wearing neon-green t-shirts that glowed in the dark, holding up anti-fracking and anti-war signs while chanting slogans, only to be eventually drowned out by Hillary Clinton supporters.

What we didn’t see were the massive—and potentially violent—protests that many had predicted. But the dissent in each hall demonstrates an important part of this democracy; the conventions haven’t always been this way, and they have changed frequently over the course of this country’s history. It is possible that after this election, the parties may look at the nominating conventions in a new light and change the rules again. But one thing we do know for sure about conventions is that as delegates make their way from Philadelphia back to their home states, Americans will swiftly turn their attention to the brutal battle for the White House. Expect a slew of negative ads, gaffes followed by explanations or refutations, small moments played out as headline news, and a very weary American public. The conventions themselves will very soon be a distant memory as we march toward November 8.

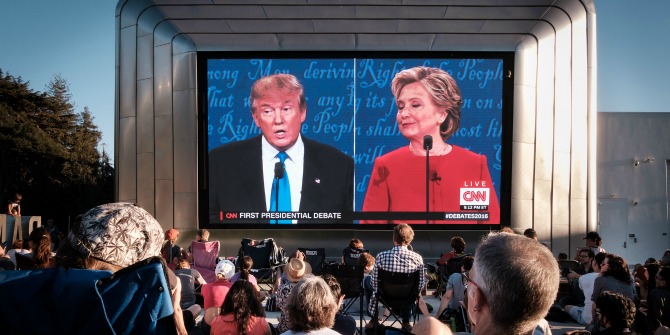

Featured image credit: Lorie Shaull (Flickr, CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2atlBLl

_________________________________

Lindsay Hoffman – University of Delaware

Lindsay Hoffman – University of Delaware

Dr. Lindsay Hoffman is an Associate Professor, and Associate Director of the Center for Political Communication at the University of Delaware. Her research examines how citizens use internet technology to become engaged with politics and their communities. She also studies individual and contextual effects of media on individuals’ perceptions of public opinion; the effects of viewing political satire on knowledge and participation; social capital and communication; and factors leading to public-affairs news use.