On an average day in the USA, seven children and teenagers will be shot dead. In Another Day in the Death of America: A Chronicle of Ten Short Lives, journalist Gary Younge tells the stories of ten lives lost on one single day: 23 November 2013. This is a powerful, timely and important contribution to the debate on US gun culture and how US society particularly treats its African American citizens, writes Peter Carrol.

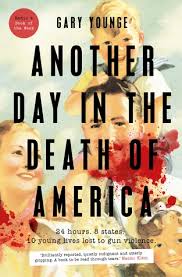

Another Day in the Death of America: A Chronicle of Ten Short Lives. Gary Younge. Faber Publishing. 2016.

Gary Younge’s powerful indictment of America’s gun culture

Gary Younge’s powerful indictment of America’s gun culture

To many outsider observers, America’s gun culture and its associated death toll is viewed with a mixture of confusion and bafflement. How can an advanced, sophisticated nation tolerate such daily carnage without taking action?

This is the premise of Gary Younge’s book, Another Day in the Death of America: A Chronicle of Ten Short Lives, which features ten chapters reporting ten gun deaths that occurred on Saturday 23 November 2013. Younge is an experienced journalist who has reported on America for the Guardian for over a decade, and has written eloquently about his experiences of racism as a black British man living in and working in the USA. This book aims to bring his perspective as an ‘anthropological alien’ to provide an objective account of America’s gun culture; but as the deaths and injuries disproportionately affect America’s black population, Younge, father of two young children and long-term resident in inner-city Chicago, admits that he has a personal stake in the issue or, as he puts it, ‘black skin in a game where the odds are stacked against it’.

The stories of the ten victims are told through their friends, families and through media and police reports, detailing the known circumstances of their deaths. Eight of the ten victims were African American, while all of them were under twenty: figures chosen to reflect the diversity of the average number of children killed by guns each day in America by other Americans. The November date was selected at random. Two of the victims were killed accidentally by their friends. Three appear to be implicated in gang violence and victims of reprisal shootings. Two victims appear to have been killed by stray bullets as they walked the streets. What unites them all is that their lives ended in an environment where access to guns is easy, and that they were citizens in a society that is unwilling, or unable, to do anything about it.

Younge powerfully describes a world of disadvantage, street gangs warring over the drug trade and the everyday existence of young lives in the mostly poor towns and cities in which the killings took place. Some of the children’s parents are doing their best with the odds stacked firmly against them, while others are neglectful and largely absent, their lives destroyed by addiction and poverty. But Younge does not offer judgement on the children’s backgrounds, making clear that the tragedy of gun violence can randomly strike any person at any time in these environments: in this sense, all of the victims are innocent.

Image Credit: Houston Gun show at the George R. Brown Convention Center (CC BY 2.0)

Image Credit: Houston Gun show at the George R. Brown Convention Center (CC BY 2.0)

Younge emphasises that this book is the first significant attention these victims have received beyond their immediate friends and family. The question that Younge poses several times is whether America would tolerate these deaths if they occurred in the areas and communities where the wealthy professional classes live. The societal response to the Sandy Hook shooting, where twenty school children and six adults were killed in their classrooms in a Connecticut school, is compared unfavourably with the relative invisibility of these deaths. But the fact that there was no legislative change to restrict gun access following the events at Sandy Hook, Younge reflects, makes the daily deaths that take place in America’s poor communities even less likely to draw a substantive response.

One of the flaws in the book is that the device of selecting a day at random means that Younge is unable to expand his reporting to other victims if the families refused to be interviewed or to cooperate with his study. This constraint means that some of the profiles are inconsistent, and two of the victims’ case studies are instead filled with Younge’s analysis of the social, political and cultural factors that have led to America’s current impasse.

Younge discusses how the history of slavery and the social, economic and political discrimination against African Americans in the twentieth and early twenty-first century are the main factors behind the higher probability of black men being unemployed, in prison or dead by the age of 25, compared to the white population. He provides a short history of the National Rifle Association (NRA), America’s powerful pro-gun lobby group, and the second amendment, which bestows the right for citizens to bear arms. Younge makes the argument that the sociological context rather than individual responsibility is the primary factor behind black underachievement in US society, supporting it with judicious use of academic studies and statistics. But what is missing from his analysis is any sense of the perspective of the owners of the 270 million guns in America or the NRA, whose views, motivations and deep commitment to protecting the second amendment are an important component of the victim’s deaths. How do these groups justify obstructing policies that would likely bring a reduction in gun deaths and prioritise their right to own guns over others’ right to live? Younge attributes blame chiefly to the NRA, but their voice is not heard, and his criticisms stand unchallenged.

Despite these limitations, the book is a timely and important contribution to the debate on how US society treats its African American citizens. Since 23 November 2013, racial tensions have regularly erupted in the aftermath of allegations of police brutality or civilian fatalities, usually captured by citizens on their smartphones and circulated on social media. The killings of Michael Brown and Eric Garner have triggered serious outbreaks of rioting, with civil rights protesters coalescing around the #blacklivesmatter movement, offering the prospect of a concerted campaign to address America’s gun culture.

But despite these developments, Younge closes the book on a pessimistic note, writing that an effective counter-action against the NRA and a change in the law remain highly unlikely, meaning that an end to the daily carnage and tragedy that stalk American life is an elusive prospect. Younge’s sober and reflective memorial to the victims befits the chilling truth that these children’s deaths at the hands of guns are so commonplace in America that they are banal, and that each day the tragedy will continue to roll on relentlessly.

This review originally appeared at the LSE Review of Books.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2g300Rl

——————————————–

Peter Carrol – LSE

Peter Carrol is a Media Relations Officer at LSE and LSE MSc graduate in Politics and Communication. Read more by Peter Carrol.

We Yanks shoot each other dead at 11,000 annually. After five and half years we surpass the total U.S. death count for the Vietnam War, which was a sixteen years long war. I remember growing up and being very concerned over the possibility of conscription. Yet, we Yanks are dying from others’ bullets at three times the rate that we died in Vietnam. Compare that to the U.K. which, according to the Times, saw 39 gun homicides in 2011. At five times the population the U.S. would have 195 per capita of the population at that rate, not 11,000. Enabling this carnage is the 2nd amendment, which is held sacred by the view that Yanks would still be British were it not for their guns. Never mind that Canada and other colonies that took the longer route of diplomacy and negotiation resulted in independence, too many Yanks worship their guns.