Donald Trump was the clear Electoral College winner in the 2016 election, despite losing the popular vote by a wide margin to Hillary Clinton. Anthony J. McGann, Charles Anthony Smith, Michael Latner and Alex Keena write that, unless the Supreme Court stops congressional gerrymandering, President Trump can guarantee re-election in 2020 – even if he loses by 6 percent.

Donald Trump was the clear Electoral College winner in the 2016 election, despite losing the popular vote by a wide margin to Hillary Clinton. Anthony J. McGann, Charles Anthony Smith, Michael Latner and Alex Keena write that, unless the Supreme Court stops congressional gerrymandering, President Trump can guarantee re-election in 2020 – even if he loses by 6 percent.

When the US Supreme Court takes up the issue of partisan gerrymandering this year, they will decide not only the fate of popular control in the House of Representatives and many state legislatures, but quite possibly the Presidency as well. If four Republican controlled state governments (Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin and Florida) change the way they allocate Electoral College votes, President Trump could be re-elected in 2020, even if he loses the popular vote by 6 percentage points. All the states need do is to allocate Electoral College votes by congressional district (like Nebraska and Maine), instead of giving all of the state’s electors to the statewide winner.

Of course, this strategy only works to the benefit of the Republicans because the congressional districts in these states are heavily gerrymandered. As we argue in our book Gerrymandering in America, the congressional districts in many states are drawn to advantage the Republican Party. For example, in Pennsylvania in 2012 the Republicans took 13 out of 18 House districts even though the Democrats received more votes. If this partisan gerrymandering were outlawed, then allocating Electoral College votes by congressional district in the four states would actually disadvantage the Republican candidate for President.

However, if the Supreme Court continues to allow partisan gerrymandering – as it has since its decision Vieth v. Jubelirer in 2004 – then the plan is highly effective and there is nothing that can stop the four states adopting it. Allocating Electors by congressional district is clearly legal – Nebraska and Maine already do it this way. Furthermore, the Republicans control the state legislature in all four states.

How allocating Electors by congressional districts could benefit the Republican candidate

Surprisingly, the strategy that is most effective for the Republicans is to change how Presidential Electors are allocated in certain states that voted for Trump in 2016.

Of course, the Republicans would get an advantage by allocating Electors more proportionally in states that Clinton won. The problem is that this would require the support of Democrats. For example, Republican legislators in Virginia and Minnesota have already proposed such measures, and Stephen Wolf describes this as an attempt to “gerrymander the electoral college”. The problem is that both these states have Democratic governors, who would surely veto such proposals. Similarly Harry Enten at fivethirtyeight.com shows that if all states allocated Electors by Congressional districts, the Republicans could win the Presidency despite a 5 percent popular vote deficit. Again the problem is that this would require Democratic controlled states to agree to such a system.

However, in Wisconsin, Michigan and Florida, Republicans control both the state legislature and the governorship. They can change how Presidential Electors are allocated in these states. In Pennsylvania, the Republicans control the state legislature, but there is a Democratic Governor who would presumably veto. However, there are gubernatorial elections in 2018 and Governor Tom Wolf appears vulnerable.

But how would making changes in states that already voted for Trump further benefit him? In 2016 all Pennsylvania’s 20 Electors went to Trump. If Pennsylvania’s allocated its Electors by Congressional districts, Trump would only have received 14 of them. However, a swing of less than 1 percent would have given all 20 Pennsylvania Electors to Clinton. By going to allocation by Congressional district, the Republicans can ensure they receive most of Pennsylvania’s Electors, even if they get fewer votes than the Democrats. This amounts to taking out insurance against a swing to the Democrats.

We can consider the effect of changing the allocation of Presidential Electors in the four states (Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin and Florida) compared to the current system. We do this using the data for the presidential vote by congressional district compiled by Stephen Wolf at Daily Kos, and assume that any vote swing is uniform across the districts.

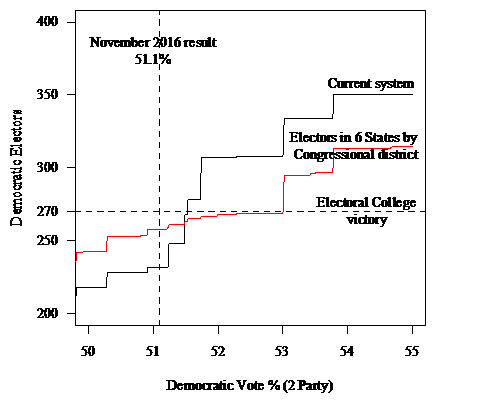

As you can see in Figure 1 below, in 2016 Clinton received 51.1 percent of the two-party vote and was allocated 232 Electors. However, a very small swing would have changed all that – if she had won 51.6 percent of the vote, she would have reached the 270 Electors required to become President.

Figure 1 – Democratic Presidential Electors if six states (ME, NE, PA, MI, WI, FL) allocated electors by congressional district

Things would be very different if the four states allocated Electors by Congressional district. Clinton would have received 258 Electors for the 51.1 percent of the vote she won. However, she would need to reach 53.1 percent of the popular vote to reach the 270 Electoral College votes needed to win the Presidency. That is, she could have won the vote by 6 percent and still not been elected President.

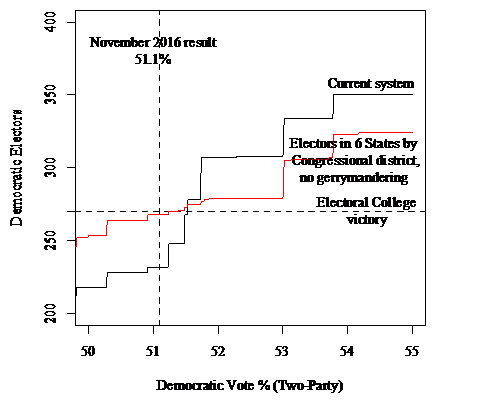

This would not be possible if Congressional districts were not gerrymandered. We can show what would happen if the four states changed how they allocated their Presidential Electors, but are not allowed to district in a way advantages one party over the other. As Figure 2 illustrates, we find that if the Democrats win 51.3 percent of the vote, they receive the 270 Electoral College votes required to win the Presidency. Without gerrymandered districts, changing how Electors are allocated in the four states actually hurts the Republicans.

Figure 2 – Democratic Presidential Electors if six states (ME, NE, PA, MI, WI, FL) allocated electors by congressional district, but Congressional gerrymandering is not allowed

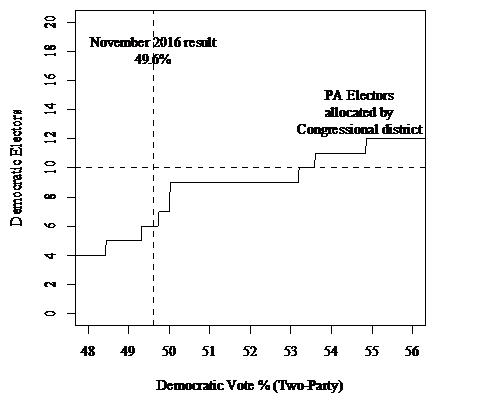

When we consider an individual state, we can see why allocating Electors by Congressional districts is so advantageous to the Republicans. Pennsylvania has four districts that are overwhelmingly Democratic, which soaks up much of the Democratic vote and allows the Republicans to win nearly all the remaining districts. In 2016 Trump won the state, with Clinton receiving 49.6 percent of the two-party vote. As Figure 2 shows, if Electors were allocated by Congressional district, this would have given the Republicans 14 out of the 20 Pennsylvania Electors. A small swing to the Republicans would have given them 16 out of 20. However, even if Clinton had won 53 percent of the vote, the Republicans would still have got 11 out 20 electors. Indeed even if Clinton had won by 19 points, she would still only have got 12 electors out of 20.

Figure 3 – Democratic Presidential electors from Pennsylvania, if electors allocated by congressional district

The Choice facing the Supreme Court

This is why the position the Supreme Court takes on partisan gerrymandering is so important. If the Court continues to allow partisan gerrymandering, then President Trump could be re-elected in 2020, even if he loses the popular vote by 6 percent. All it takes is for four Republican controlled states – Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Michigan and Florida – to allocate Presidential Electors by congressional district, as Maine and Nebraska do now.

If, however, the Court decides that partisan gerrymandering is unconstitutional, this plan doesn’t help the Republicans at all. It only works because the congressional districts in the four states have been drawn to strongly advantage the Republicans.

The Supreme Court is likely to consider the appeal of Whitford v. Gill later this year. A federal court has decided that the districts for the Wisconsin State Legislature were an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander.

However, since its decision in Vieth v. Jubelirer (2004), the Supreme Court has found that the courts should not intervene in partisan gerrymandering cases, arguing that there does not exist a legal standard for judging them. This judgment set the stage for the current gerrymandering of the House of Representatives. In our book, we show that partisan bias tripled in the redistricting cycle following the Vieth judgment. State governments did not have to fear judicial reprimand, so they were free to push partisan gerrymandering to the limit. As a result, we argue that the Republicans will retain control of the House until at least 2022.

If the Supreme Court takes the same line it did in Vieth v. Jubelirer and overturns the Federal Court’s decision in Whitford v. Gill, then not only will the partisan gerrymandering of Congress continue, but there is nothing to stop this gerrymandering from determining control of the Presidency as well. This is what is at stake when we consider President Trump’s nominee to the Supreme Court.

This article is based on the authors’ new book, Gerrymandering in America (Cambridge, 2016).

Editor’s note: This article originally suggested that Pennsylvania had a Republican Governor. The text has now been corrected to reflect that Pennsylvania has a Democratic Governor, Tom Wolf.

Featured image credit: Truthout.org (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2kN9LUG

_________________________________

Anthony J.McGann – University of Strathclyde

Anthony J.McGann – University of Strathclyde

Anthony McGann is a Professor at the School of Government and Public Policy in at the University of Strathclyde. He is currently affiliated with the Institute for Mathematical Behavioral Sciences and the Center for the Study of Democracy at the University of California, Irvine. From 2008-2009 he was the co-director of the University of Essex Summer School in Social Science Data Analysis and Collection.

Charles Anthony Smith – University of California, Irvine

Charles Anthony Smith – University of California, Irvine

Charles Anthony Smith is an Associate Professor of Political Science at UC Irvine. His research is grounded in the American judiciary and focuses on how institutions and the strategic interaction of political actors relate to the contestation over rights. He is the author of The Rise and Fall of War Crimes Trials from Charles I to Bush II (Cambridge University Press 2012) and the recipient of the 2011 Bailey Award for the best paper on gay and lesbian politics for the paper “Gay Rights and Legislative Wrongs: Representation of Gays and Lesbians,” which he coauthored with Benjamin G. Bishin.

Michael Latner – California Polytechnic State University

Michael Latner – California Polytechnic State University

Michael Latner is an Associate Professor of Political Science and Director of the Masters in Public Policy Program at California Polytechnic State University. His teaching and research interests include political participation, representation, and civic technology.

Alex Keena– University of California, Irvine

Alex Keena– University of California, Irvine

Alex Keena is a PhD student at the School of Social Science at the University of California, Irvine.

I will admit, I did not read the entire article word for word. To do so, it would have had to get to my significant problem with this hypothesis earlier, rather than bury it, if it did. But to my understanding, all states utilize the popular vote of the entire State to determine which candidate wins their electoral votes. And then that winner receives them all.

Under that structure, internal gerrymandering of Congressional districts has no effect on the outcome of the Presidential election. How the House of Representatives is controlled? Sure. But that is nothing new at all. The party in control has always had that power. Nothing some new concept. So…?

Withdraw my comment… I did not catch that those States were considering changing the way they allocate their electoral votes… different from how they were for the 2016 and earlier elections… so… nevermind.

Hillary’s “popular vote” numbers were from California 100%, in fact in California Hillary outperformed Obama, the other 49 states Obama bested her.

Los Angeles & San Diego counties population is greater than the 10 lowest populated states COMBINED.

It is not disputed that California has given drivers licences to undocumented persons(illegals) for about 10 years, millions of them are in California.

What everybody never mentions and somehow we dont know?? about on a grand scale is that in California all year long there is a $35 million California endowment that assists undocumented persons to be political, to get their family and friends and neighbors to VOTE !!

They register them for schooling and health to vote and food stamps everything imaginable to assist them integrating , T shirts and bus stops and bill boards are plastered across California stating in huge bold lettering ,…iVOTA!, There are several versions but the iVOTA! campaign leaves nothing to deny as to the goal, see below.

http://i67.tinypic.com/1zd823a.png

i VOTA! California endowment to register illegals to vote and get a Cal drivers license, register for school, college, register for Social Security and Welfare, Food Stamps.

their website admit to registering millions of undocumenteds since 2008.

“http://i66.tinypic.com/16m6smb.png

http://i67.tinypic.com/mipfdv.jpg

WAGE THEFT 2 CHECKS 300K

iVOTA!

http://i63.tinypic.com/mo42e.png

luciamos con votar!

These iVOTA! signs are plastered over California every year!

http://www.pewhispanic.org/…/ph_election-2016_appen…/”>

http://www.pewhispanic.org/…/ph_election-2016_appen…/”>

Democrats love illegal immigrants, particularly at election time. In between, they need gardeners and nannies, too.

The governor of PA is a Democrat and has been since 2015! Someone needs to fix this post.

Thanks for pointing that out Charlotte, the text has now been corrected.

– Chris Gilson, Managing Editor, USAPP

Thank you! This is a really interesting topic.

The popular vote is absolutely positively, beyond a reasonable doubt to a moral certainty irrelevant in a presidential election. Anyone advancing such an argument clearly has not read the US Constitution. Would matter if a candidate lost the popular vote by 15% so long as they win 270 electoral votes. This article and any others that cry over a presidential election where the elected candidate looses the popular vote and wins the presidency has not read or can not comprehend the presidential election method mapped out in the UE Constitution. Any state passing legislation tying the awarding of their electoral vote to the total popular vote will have that legislation over turned by the US Supreme Court.