Wage theft is pervasive in America; in a new study of low-wage workers across the US, Daniel J. Galvin finds that 16 percent were paid less than their state’s minimum wage. He also finds that workers in those states which had greater employment law protections tended to have a lower chance of experiencing wage theft, and that those protections tended to be in states with unified Democratic governments. With Donald Trump’s Labor Department unlikely to do much to address the problem, he writes that workers’ advocates will need to build coalitions and work with Democrats at the state and city level in order to ensure workers are protected from wage theft.

Wage theft is pervasive in America; in a new study of low-wage workers across the US, Daniel J. Galvin finds that 16 percent were paid less than their state’s minimum wage. He also finds that workers in those states which had greater employment law protections tended to have a lower chance of experiencing wage theft, and that those protections tended to be in states with unified Democratic governments. With Donald Trump’s Labor Department unlikely to do much to address the problem, he writes that workers’ advocates will need to build coalitions and work with Democrats at the state and city level in order to ensure workers are protected from wage theft.

Wage theft is pervasive, but often remains hidden. When employers cheat employees out of the wages they’ve earned, few complain out of fear they’ll be fired, deported, or abused. Indeed, as the Trump administration has begun more aggressive deportations, immigrant workers have already become less likely to come forward.

The cases of wage theft we are able to see are either brought to light through the bravery of workers who feel they must take a stand or through Department of Labor investigations, lawsuits brought by determined attorneys general like Eric Schneiderman of New York, or painstaking efforts to root them out by innovative state labor commissioners like Julie Su in California. Journalists have helped raise awareness as well.

A New York Times exposé of the nail salon industry in New York City, for example, revealed that new employees—usually undocumented immigrants—were often required to pay $100 for the opportunity to work, forced to “train” for weeks without pay, and were then paid as little as $30 a day for 12-hour days, six or seven days a week, all in violation of federal and state minimum wage and overtime laws.

Almost everything else we know about the problem comes from academic investigations. The most widely cited study, conducted back in 2008, surveyed 4,387 hard-to-reach low-wage workers in New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles and found that 26 percent had been paid less than the minimum wage in the previous week, with 60 percent underpaid by more than $1 per hour. More than three quarters of those who worked over 40 hours did not receive any overtime pay.

My own recent research used Current Population Survey (CPS) data to generate estimates of minimum wage violations across all 50 states between 2005 and 2013. Circumventing the problems and biases that are baked into complaint-based and employer-reported data, the CPS data enable us to capture trends in wages and hours that would otherwise be invisible.

I found that between 2005 and 2013, about 16 percent of low-wage workers were paid less than their state’s legal minimum wage each year. In 2013, for example, these victims of wage theft worked an average of 32 hours per week and earned an hourly wage of only $5.92.

These were not just paycheck rounding errors or a few lost tips. Had these workers earned their applicable minimum wage, they would have received an average hourly wage of $7.68, meaning that they were cheated out of 23 percent of their income ($1.76 per hour) on average. While an estimated income loss of 23 percent may seem high, it is actually toward the lower end of other published estimates.

The CPS data don’t tell us how employers withheld the wages. But we know that employers often commit wage theft by mandating off-the-clock work, paying their employees a flat rate irrespective of hours worked, making illegal deductions, withholding tips, misclassifying their employees as exempt, or simply refusing to pay for work performed.

I focused on minimum wage violations. This type of wage theft is not as expensive or as widespread as overtime violations (and possibly employee misclassification) but it disproportionately affects our most vulnerable workers in society: immigrants, people of color, less educated workers, younger workers, women, and others who can least afford to be underpaid.

When low-wage workers are cheated out of even a small percentage of their income, it can cause major hardships like being unable to pay for rent, child care, or put food on the table. Minimum wage violations are also deleterious to society, as they contribute to widening income inequality, wage stagnation, and chronically slow growth in living standards—interrelated problems that are viewed by many as the most pressing of our time.

The problem is likely to get worse under President Donald Trump, whose Labor Department may be inclined to revert to its old ways under George W. Bush, when it was lambasted by the Government Accountability Office for “sluggish response times, a poor complaint intake process, and failed conciliation attempts” and for leaving “thousands of actual victims of wage theft who sought federal government assistance with nowhere to turn.” This raises the question: where should exploited workers turn during the Trump presidency?

With private sector labor union membership down to about 6.5 percent, precious few workers will be able to take advantage of union representation and redress through mediation or arbitration. The vast majority of workers will have no defense other than state, county, and municipal-level laws. Most states and localities have their own employment laws on the books, but the majority of these are weak, and their labor departments toothless. These laws can and should be strengthened.

Of course, political conditions are not particularly favorable for progressive policy change. Only six states (and Washington, D.C.) are currently controlled by Democrats. Two-thirds of the biggest cities have Democratic mayors, though, and may be amenable to passing more protective legislation and enforcing workers’ rights.

Workers and their advocates will simply have to push for progressive policy change wherever and whenever they can.

But it’s not a fool’s errand. In my research, I have found that simply increasing the penalties for wage violations – even in the absence of strategic enforcement by regulators – can by itself reduce the incidence of wage theft.

What to do?

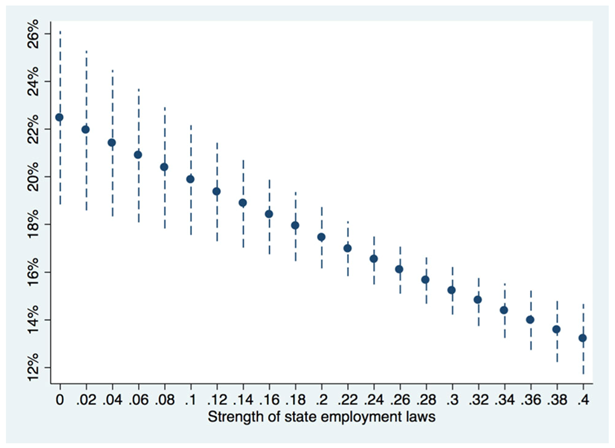

In my analysis, I found that in states with the toughest penalties for unscrupulous employers, workers had a significantly lower likelihood of experiencing minimum wage violations in 2013 than comparable workers in states with weaker statutes (holding constant demographic, economic, and other factors), as Figure 1 shows.

Figure 1 – Predicted probability of minimum wage violation rate given strength of state employment laws, low wage workers, 2013

For example, the probability that a low-wage worker would suffer a minimum wage violation in a state like Massachusetts or New Mexico (with some of the strongest employment laws in the country) was about 14 percent, while a comparable worker in Virginia (with some of the weakest) had about a 22 percent probability of experiencing wage theft, all else equal.

We can get an even better picture of the laws’ impact by looking at the violation rate before and after policy changes. Between 2006 and 2013, a dozen states (Arizona, California, Illinois, Iowa, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Rhode Island, Texas, and Washington) passed new statutes heralded as significant anti-wage theft laws.

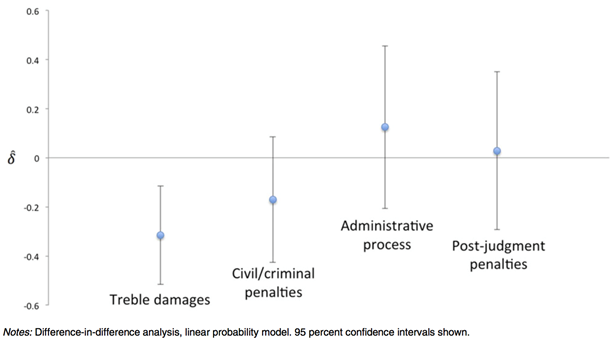

Among the different mechanisms chosen to combat wage theft, I found that only one type of reform was associated with significant declines in the probability of wage theft: the introduction of treble damages (three times the back wages owed) in wage violation cases (Figure 2). Those laws were enacted in Arizona, Massachusetts, New Mexico, Ohio, and Rhode Island.

The remaining seven states introduced more modest penalty increases (Iowa, New York, and Texas), new small-claims administrative processes (Illinois and Maryland), and failure-to-pay-up penalties (Washington and California). But none of those reforms reduced the incidence of wage theft after the laws were passed.

Figure 2 – Effectiveness of policies aimed at reducing wage theft

Another lesson to draw from these cases is that political conditions matter a lot – most of all, which party is in power. In nine of the twelve states that enacted stronger laws, Democrats controlled both houses of the legislature and the governorship. Two of the laws were passed via ballot initiatives (Arizona and Ohio); and only one was enacted under unified Republican government (closing Texas’s “Theft of Service” law loophole).

Just as important for the bills’ success were the protests and lobbying efforts of progressive coalitions made up of workers’ advocacy groups (“alt-labor”), traditional labor unions, legal advocates, and business groups seeking to level the playing field. Working with sympathetic Democratic legislators, those broad coalitions overcame the opposition of right-wing groups and Republican lawmakers to bolster their states’ capacity to defend workers’ rights.

To combat wage theft, in other words, workers’ advocates have usually needed to hit the trifecta: unified Democratic government, a broad coalition of politically deft advocacy groups, and a policy design that actually deters wage theft.

At the national level, Democrats introduced well-crafted legislation in Congress in 2016 to amend the Fair Labor Standards Act and make treble damages available to workers, but it will be many years before such legislation gets a fair hearing in Congress. In the meantime, the main action will continue to take place at the state and local levels.

There, workers’ rights advocates will need to build coalitions, develop policy proposals to strengthen state and local laws, and work with Democratic politicians, both to help build Democratic majorities and to enjoy good working relations when the opportunity to enact stronger legislation arises.

Republicans now control both legislative chambers in 32 states — the most ever for the party. Democrats control both chambers in 13 states, but only 6 of those states also has a Democratic governor. Thirty-three of the nation’s 51 biggest cities, however, have a Democratic mayor, which suggests that reform may be more possible at the municipal level (in states where Republican legislators haven’t already passed preemption laws in anticipation of local efforts to protect workers).

In Chicago, for example, a coalition of workers’ advocates led by Arise Chicago collaborated with supportive aldermen and a Democratic mayor to pass a strong anti-wage theft ordinance in 2013 which revoked the business licenses of those found guilty of wage theft. In 2015, an even broader coalition got a similar ordinance passed at the county level. With a Republican governor in power, state-level policymaking has ground to a halt and the state labor department’s enforcement capacity has been badly diminished. But with stronger public policies at the city and county levels, millions of workers will see real benefits.

The same formula, applied elsewhere, could provide much-needed help to workers during the Trump administration.

This article is based on the paper, “Deterring Wage Theft: Alt-Labor, State Politics, and the Policy Determinants of Minimum Wage Compliance” in Perspectives on Politics.

Stickman in pickpocket peril by Ruth Hartnup is licensed under CC-BY 2.0.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2mEmJEd

_________________________________

Daniel J. Galvin – Northwestern University

Daniel J. Galvin – Northwestern University

Daniel J. Galvin is an associate professor of political science and a faculty fellow at the Institute for Policy Research at Northwestern University.