Do people’s opinions on policy debates follow those of the political party they support? In new research using a nationally representative survey, Kevin J. Mullinix finds that knowing that their party supports certain legislation means that people are more likely to support that legislation, and that this effect is more pronounced when parties are highly polarized. This effect is not absolute, however; when an issue is personally important, people will not blindly follow their party’s lead.

Do people’s opinions on policy debates follow those of the political party they support? In new research using a nationally representative survey, Kevin J. Mullinix finds that knowing that their party supports certain legislation means that people are more likely to support that legislation, and that this effect is more pronounced when parties are highly polarized. This effect is not absolute, however; when an issue is personally important, people will not blindly follow their party’s lead.

When people express support for a political candidate or take a side on a policy debate, are they blindly following their political party? Late night comedic television programs interview seemingly ordinary people on the street and provide amusing demonstrations, for example, of Democrats who strongly support for Trump’s tax proposals and quoted remarks when told, incorrectly, that they are from Hillary Clinton. After a bit of laughter, more contemplative viewers might pause – and potentially worry – when they remember that these foolish-looking people get to vote. Political parties and elected officials do indeed shape public opinion, but I argue that there are limits to the extent people will follow their party’s lead.

Some research suggests that whether people support a policy depends, quite simply, on whether their preferred party supports or opposes the policy. Experiments conducted in the United States demonstrate that conservatives will support a conservative welfare policy when that policy is endorsed by the Republican Party, but then oppose the same policy when supported by the Democratic Party. Liberals demonstrate a similar willingness to follow the Democratic Party. Examples of such behavior exist outside of the experimental setting; for instance, a recent US survey found that Republicans’ support for missile strikes against Syria quadrupled after Trump’s recent strikes. Should we be concerned that elected officials and parties exert such considerable influence on public opinion?

Public policy problems and solutions are often complex. Most people do not have the time or motivation to research the intricacies of every issue domain, and as such, they often look to their party – a trusted source – for guidance. When people hear that officials from their party support a policy or when they see a “D” or an “R” next to a candidate’s name on a ballot, they can use the party endorsement as a cognitive shortcut or “cue.” Relying on such party endorsements reduces the time required to watch and read the news. However, such reliance also allows parties to shape people’s attitudes. Further, there are studies which demonstrate that the mere presence of party endorsements in political news prompt unconscious biases. Such a dynamic may, for example, color perceptions of inauguration crowd size. Still other evidence suggests that differences in factual beliefs reflect a type of “partisan cheerleading”.

Building on this research, I recently studied the extent to which political parties sway public opinion. I was primarily focused on understanding situations in which people are more likely to follow their party’s lead, and situations in which people abandon their party’s policy positions.

To do so, I carried out an online survey designed to be nationally representative of the United States. Within the survey, respondents received news articles on two different public policies and were then asked for their opinions on the issues. The articles focused separately on: a proposal to cut income taxes, and the “Student Success Act,” an effort to reduce the federal government’s role in education policy. Both news articles were based on real-world policies proposed by Republicans.

While all respondents received articles with the same general content, I embedded an experiment in the study. Respondents were randomly assigned – unknowingly – to receive slightly different versions of the articles. One group of people received articles that described the policies but never mentioned which party supports the proposed legislation (i.e., they received “No Party Cue.”). A second group received the same articles, but were told that Republicans support the proposals and Democrats oppose them. A third group received the same articles, but were told that Democrats support the policies and Republicans oppose them. Both policies are, in reality, proposals put forth by officials from the Republican Party. Thus, people in the second group receive what I call “Traditional Party Cues” and the third group are provided “Reversed Party Cues.”

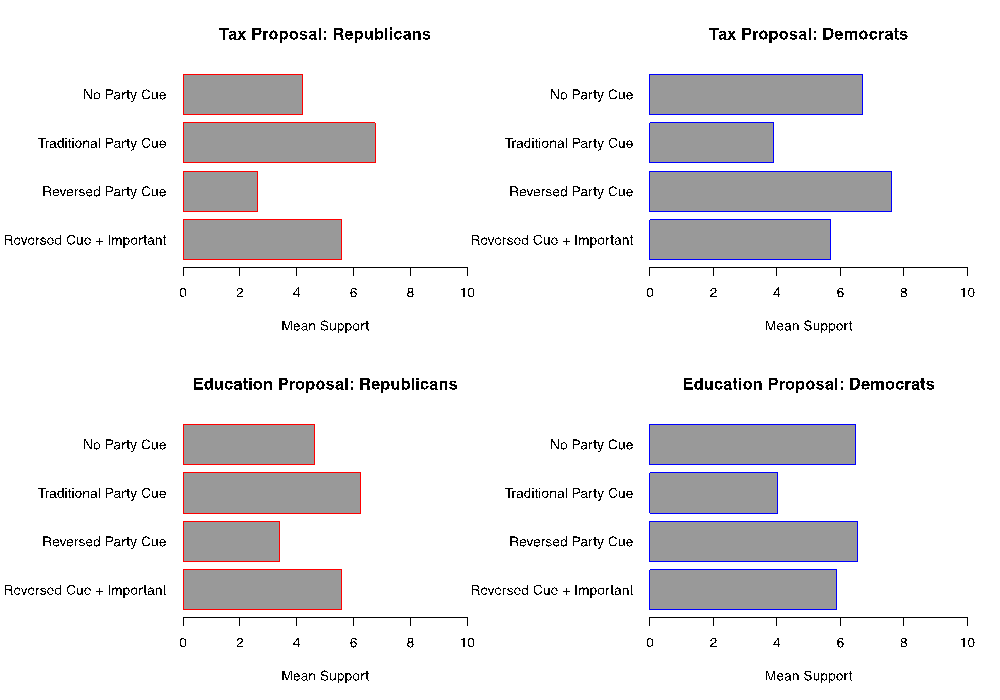

As anticipated, the results illustrate that party cues shape policy preferences. By comparing the “No Party Cue” to the “Traditional Party Cue” conditions in Figure 1, we observe the effect of telling respondents that Republican lawmakers support the legislation and Democrats oppose it. As expected, Republicans, on average, become more supportive of the legislation when told their party supports it, and similarly, Democrats become less supportive when told their party opposes it.

Figure 1

Perhaps more troubling is the reversed party cue condition where people follow their party’s lead even when their party takes a stance that is completely out-of-step with reality. Comparing the “No Party Cue” to the “Reversed Party Cue” situations, Republicans are more opposed to cutting income taxes and the Student Success Act when told their party opposes such measures. Democrats follow the reversed party cue as well, but only on the tax issue.

In other experimental conditions not shown here, I find that these party cue effects are more pronounced when people are told that the parties are polarized on the issues. That is, when the articles suggest that it is an “incredibly competitive partisan atmosphere” and that parties are “highly polarized,” people are even more supportive of their party’s stated position. In an era in which political parties are increasingly polarized, the findings suggest that political parties have considerable leverage on people’s attitudes.

Yet, there is room for optimism. In looking at previous studies, I wondered if the effects of reversed party cues, like those shown above, were due to people lacking a motivation to care about and pay attention to policy information. I wanted to know if people would still “blindly” follow their party if they thought an issue was personally important. To address this possibility, I inserted a statement in the tax article from a policy expert that said “how this issue is handled will have direct consequences for the daily lives of nearly all Americans…..this will have an impact virtually every time citizens get a paycheck.” Similar but distinct language was used for the education proposal.

The results are shown in the bottom bar of each figure (“Reversed Cue + Important”). It appears that when people think an issue is personally important, they do not blindly follow their party’s lead. The effect of the reversed party cue is not only eliminated when coupled with the importance statement, but people seem to pay attention to the information and shift toward their party’s position in reality. They pull away from their party’s position as stated in the article. That is, Republicans shift toward what they are told is the Democratic position; in some respects, this is an “over-correction” of attitudes.

When political parties take stands on policies and endorse candidates, they provide short-cuts to help us make sense of politics. People seem quite eager to follow their party’s lead and our willingness to follow our party can, at times, make us look foolish. And as noted above, these effects are accentuated when parties are polarized on the issue.

Yet, the influence of political parties on public opinion is not without limits. The mass public is not merely an obedient dog on a leash controlled by political parties; we seem, at times, capable of slipping our partisan collars. When people believe that a policy proposal may impact their daily lives, they can shirk their party’s endorsement and focus on the substantive merits of a policy proposal.

“Republican Elephant & Democratic Donkey – Icons” by DonkeyHotey is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Read articles by Partisanship and ‘Preference Formation: Competing Motivations, Elite Polarization, and Issue Importance’, in Political Behavior.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2pxlfOm

_________________________________

Kevin Mullinix – Appalachian State University

Kevin Mullinix – Appalachian State University

Kevin Mullinix is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Government and Justice Studies at Appalachian State University. His research focuses on public opinion and political behavior and has recently been published in Political Behavior, Political Communication, and the Journal of Experimental Political Science.

Indeed, this partisan politics is exactly what is going on in my country, Sierra Leone, and is gradually undermining our nascent democracy, and thereby impeding economic growth and development. Political Parties need to be realistic with policies that are progressive.