At the beginning of the latter half of the 20th century, policy approaches in China and the US to providing social benefits, such as education and health care, were very different. China’s model was one of centralized control, while in the US a state-based approach to implementing social policies was favored. In new research, Daniel Béland, Philip Rocco, Shih-Jiunn Shi and Alex Waddan compare how the provision of social policy in China and the US has evolved. They find that both countries have converged to a point where the central government formulates and (in the US case, pays for) social policy while states and provinces play a major role in how those policies are implemented.

At the beginning of the latter half of the 20th century, policy approaches in China and the US to providing social benefits, such as education and health care, were very different. China’s model was one of centralized control, while in the US a state-based approach to implementing social policies was favored. In new research, Daniel Béland, Philip Rocco, Shih-Jiunn Shi and Alex Waddan compare how the provision of social policy in China and the US has evolved. They find that both countries have converged to a point where the central government formulates and (in the US case, pays for) social policy while states and provinces play a major role in how those policies are implemented.

China’s rise at the global stage is often viewed as a competing model for the US with its distinct political, economic and social systems. What is often neglected is the common concern both countries share in the quest for appropriate ways of governing which can accommodate the regional diversity of large territories. Decentralization is often the solution to allow room for regional policy variation while holding the whole country together. This is especially true for social policy where the important questions is which level of government – central or local – is responsible for the provision of social benefits and services. Both China and the US have experienced dynamic changes in recent decades which have moved them away from their conventional intergovernmental politics – with significant social policy implications.

China: letting local governments experiment in policy provision

In China, central-local government relations have been an ingrained component of its authoritarian polity flowing from its single-party autocracy. Counter to the appearance that the central government has predominance in policy-making local governments actually have bargaining power vis-à-vis their higher authority because of their key role in policy implementation at the local level. Since its birth in 1949, the People’s Republic has witnessed repeated attempts of decentralization during the socialist era (1949-1978) when the central leaders delegated local cadres with the autonomy to conduct policy experiments in an attempt to circumvent the stifling bondage of the central plan economy. Decentralization gained renewed momentum in the post-socialist transition after 1978 when local governments received greater autonomy in their discretion over local policy affairs. Since political performances of the local officials were evaluated upon the economic prosperity of their jurisdictions, they had now a strong incentive to promote continued business investment that would generate fiscal revenues for further development. This merit-based personnel promotion has led to China’s rapid economic growth of the past few decades.

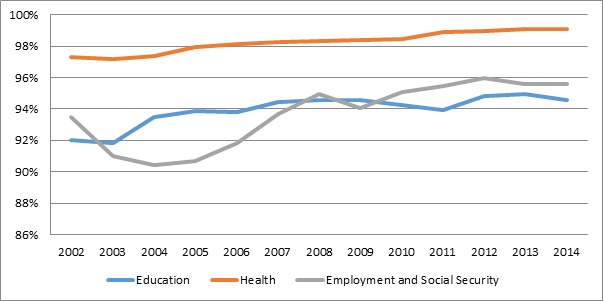

Decentralization is even more pronounced in social policy where local governments assume administrative and financial responsibilities for their implementation. As Figure 1 suggests, the share of the financial burden that falls onto local governments in key social policy areas has increased steadily, compared to the central government’s share. This holds despite the central government’s continued commitment to send financial subsidies to economically-backward regions in recent years. The territorial dimension of social policy development in China thus shows a rather loosely-coupled intergovernmental network, in which the central government dictates general policy principles but gives its subordinate local governments considerable leverage over the manner of policy implementation.

Figure 1 – Local direct budgetary expenditures in PRC on major social policy areas as a percent of total expenditures, 2002-2014

Source: Authors’ calculation based on Finance Yearbook of China, 2003-2015.

Whilst economic and fiscal decentralization has fueled the growth of China’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the same momentum proved detrimental to social integration in terms of the major financial responsibilities of local governments for social provision within their respective territories. One conceivable result is the disparate social benefits resulting from the uneven fiscal strength amongst the regions. This inequality is further compounded by the existing household registration system (hukou) that ties the individual’s entitlements to social welfare with her or his status as a resident. The strict connection between one’s resident status and social rights creates an insider/outsider problem in which migrants are denied access to local public provision where they live.

“Government Office of Shenyang 250” by By Geraldshields11 is licensed under CC BY SA 2.0; “Springfield, IL” by Patrick Gensel is licensed under CC BY NC SA 2.0

The US: decentralized in principle, but a growing role for the federal government

Meanwhile, the US is generally seen to be a federal country that has a strong role for local governments (primarily the states). The centralization of fiscal authority has been the exception rather than the rule given the diffuse, fragmented nature of the US state. At the national level, proposals for significant fiscal commitments must clear numerous hurdles, including multiple legislative committees, supermajority approval in the Senate, and presidential approval. Yet, in the early twentieth century, this began to change as progressive parties and groups used state governments as laboratories of policy innovation and helped to petition members of Congress for funds allowing states to underwrite these efforts. Moreover, states’ increasing fiscal dependence on the federal government motivated state officials to create an “organizational field” of associations with representation from all fifty states, such as the National Governors’ Association and the National Conference of State Legislators. This move has helped to buttress legislative coalitions to support the expansion of federal fiscal involvement in social policy while keeping the administration of programs in the hands of the states.

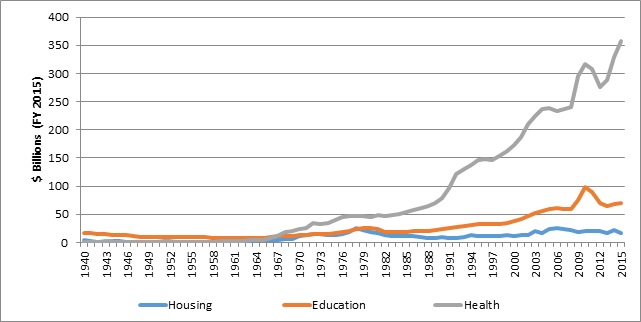

This trend continued and contributed to significant growth in the federal government’s fiscal role. As a percent of GDP, federal grants to state and local governments grew by 277 percent between 1940 and 2015. It’s important to note that this quantitative leap in federal involvement has been uneven across different policy areas. Figure 2 shows this by examining the growth in federal intergovernmental grants for community and regional development, education, and healthcare—three major categories of federal intergovernmental expenditure that experienced significant expansion during the 1960s-1970s. In the following decades, federal financial commitments to major social programs have held firm despite neoliberal attempts to roll back the welfare state.

Figure 2 – Federal Grants to State and Local Governments (Selected Categories), 1940-2015

Source: Office of Management and Budget (2016)

US federalism has favored an increase in federal intervention over time, which allows it to run its own programs and strongly pressure states to cooperate in a number of policy areas. The US welfare state is more centralized and territorially-integrated than its Chinese counterpart, due in large part to the existence of purely federal programs such as Medicare and Social Security. It should be noted, however, that the fragmented nature of the American polity constrains the extent of federal commitment in social policy. Polarized domestic partisan politics, particularly in recent decades, has led to constant recalibration of federal-state relations. As the ongoing fight over Obamacare has illustrated, conflicts between the two major parties have spilled over to the social policy domain with intricate outcomes.

Both China and the US have actually converged towards a devolved order in which the central government plays a key policy and (in the US case, fiscal) role while sub-national actors are major players when it comes to policy implementation. In social policy, the growing role of the federal government in the US and the growing role of sub-national governments in China are both embedded in similar historical and institutional rationales. These are characterized by the emergence over time of governing networks and positive feedback effects that create enduring policy legacies and vested interests that, in turn, lead to enduring patterns of centralization (in the US case) or decentralization (in the China case). Our comparative study shows that, although authoritarianism favors policy centralization and liberal democracy decentralization, these are not set in stone: alternative trajectories can occur under particular institutional and historical circumstances.

- This article is based on the paper, “Paths to (de)centralization: Changing territorial dynamics of social policy in the People’s Republic of China and the United States”, in Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2rj405M

_________________________________

About the authors

Daniel Béland – Johnson-Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy

Daniel Béland – Johnson-Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy

Daniel Béland holds the Canada research chair in Public Policy at the Johnson-Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy. He currently serves as Editor (French) of the Canadian Journal of Sociology, Co-Editor of Global Social Policy, and President of the Research Committee 19 (Poverty, Social Welfare and Social Policy) of the International Sociological Association. A specialist of fiscal and social policy, he has published 17 books and more than 115 articles in peer-reviewed journals. One of his most recent books is Obamacare Wars: Federalism, State Politics and the Adordable Care Act (University Press of Kansas, 2016; co-authored with Philip Rocco and Alex Waddan).

Philip Rocco – Marquette University

Philip Rocco – Marquette University

Philip Rocco is an assistant professor of Political Science at Marquette University. His research focuses on the political economy of policy expertise and the politics of federalism in the United States. His research has been featured in, among other venues, Journal of Public Policy, Journal of Health, Politics, Policy, and Law, Journal of Aging and Social Policy. His most recent book is Obamacare Wars: Federalism, State Politics, and the Affordable Care Act (University Press of Kansas, 2016, co-authored with Daniel Béland and Alex Waddan).

Shih-Jiunn Shi – National Taiwan University

Shih-Jiunn Shi – National Taiwan University

Shih-Jiunn Shi is a professor in the Graduate Institute of National Development, National Taiwan University. His fields of research include comparative social policy with particular regional focus on Mainland China and Taiwan, European social policy. His publications feature in peer-reviewed journals such as Journal of Social Policy, Social Policy & Administration, Policy & Politics, International Journal of Social Welfare, Public Management Review. Currently, he is conducting several research projects on the development of social policy in Greater China, and is collaborating with other scholars in the research on East Asian social policy.

Alex Waddan – University of Leicester

Alex Waddan – University of Leicester

Alex Waddan is an associate professor in American politics in the Department of Politics and International Relations at the University of Leicester. His research interests are U.S. social policy and comparative social policy, most particularly health and welfare policy. He has published four books (two as a co-author) and numerous articles and chapters. His most recent book, co-authored with Daniel Béland and Philip Rocco, is Obamacare Wars (University Press of Kansas, 2016). This book analyses the implementation of key aspects of the Affordable Care Act in the states, investigating what factors have shaped how state governments have responded to it.