Donald Trump’s ‘America First’ foreign policy doctrine has raised eyebrows in capitals across the world. Peter Finn and Robert Ledger look at what appears to be a shift away from engaging with the US executive branch by the new German coalition government. While German foreign policy intends to continue robust transatlantic relations with the US, they write, it will also seek to engage more closely with the US states and Congress, a move which many US political elites outside the executive are likely to welcome.

Donald Trump’s ‘America First’ foreign policy doctrine has raised eyebrows in capitals across the world. Peter Finn and Robert Ledger look at what appears to be a shift away from engaging with the US executive branch by the new German coalition government. While German foreign policy intends to continue robust transatlantic relations with the US, they write, it will also seek to engage more closely with the US states and Congress, a move which many US political elites outside the executive are likely to welcome.

On Sunday March 4th, the center-left German Social Democrats (SPD) approved a deal to form a government with the centre-right Christian Democrat Party (CDU, in alliance with its Bavarian sister party the Christian Social Union, CSU) of German Chancellor Angela Merkel by a margin of 66 to 34 percent. The agreement ended a five-month period of deadlock triggered by German elections last September.

There are important hints within the agreement for those seeking evidence of the shifting of alliances and priorities set in motion by US President Donald Trump. Read between the lines, and the CDU-CSU-SPD deal signals a potential shift away from a focus on primarily engaging the US executive branch to a broader approach to foreign policy.

Firstly, the text outlines a desire to work with the US Congress, that is to say as well as the White House. Secondly, the agreement describes shared transatlantic values, which could be read as a rebuke to Trump’s continued attacks on other members of NATO. Though admittedly, such attacks do seem to have become less prominent in recent months. There is an aspiration to work with individual US states, as well as other parts of the federal government, on achieving policy ends. While in a similar vein, Canada, is set on a par with the United States. An alignment that is likely sought, at least in part, because of the the perceived strengths of Canadian Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau, a leader whose star is, rightfully or not, seen as ascendant internationally.

All this points to a German foreign policy which intends to continue robust transatlantic relations while at the same time downgrading direct contact with the US President, which would likely involve some nose-holding, embarrassing exchanges on Twitter and the like. Highlighting this, the European Council on Foreign Relations stated that ‘there is a clear understanding that the situation in the US is difficult and the relationship with the US is difficult.’ Perhaps in part because of the difficulties of engaging with the Trump administration, the coalition agreement makes repeated mention of strengthening Germany’s alliance with France. As with other moments in post-war European history, for instance during the Presidencies of Richard Nixon and George W. Bush, when a less acceptable incumbent occupies the White House, European leaders – particularly in Paris and Berlin – double-down and seek to buttress EU integration and unity.

Crucially, however, while almost certainly reflecting an attempt to score points with a domestic population that has a generally low opinion of the current occupant of the Oval Office, the nod to the US Congress, individual US states and Canada in the coalition agreement may also reflect an emerging trend being driven both by US allies such as Germany, as well alternate domestic US powerbrokers, to dilute the power of, or circumvent, Trump.

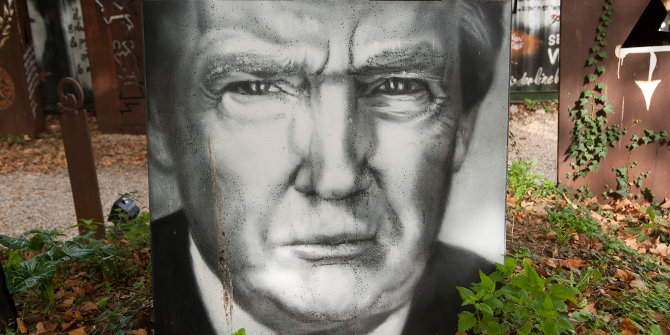

“Foreign Leader Visits” by The White House is Public Domain.

In November, for instance, a delegation of Democratic senators, mayors and governors from states such as California and Washington attended the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Bonn, Germany. This delegation were deviating from official US policy on climate change, which was re-set in June last year when Trump announced that the US would withdraw from the international deal on climate change known as the Paris Agreement.

Collectively, the delegation hosted a ritzy pavillion run under the auspices of the tagline ‘America’s Pledge: We Are Still In’. Its collective message was summed up by Senator Ben Cardin of Maryland who said, ‘I want to make it clear: The federal government is not just the president of the United States’. As such, while political elites in places such as Germany seem to be looking to water down the import of their engagement with the US executive branch by doing an end run around the executive, other domestic US power brokers are likely to meet such manoeuvres with an outstretched hand.

Further evidence of such a trend can be found in the response of US allies to the attempts of the Trump administration to undermine the nuclear deal with Iran. Germany, along with France, Britain and the EU Commission, is firmly committed to the Iran nuclear deal. This commitment is being repeatedly undermined, however, by the Trump administration. Trump himself has consistently labelled the agreement the ‘worst deal ever’ and, while granting the deal a four months stay of execution in January, stated that he was seeking to renegotiate important aspects of the deal.

While Trump continues to seek such a renegotiation, an illustration of how fragile the geopolitics that surround Iran are could be seen at February’s Munich Security Conference. Europeans were left embarrassed as Israeli Prime Minister and long-time critic of the nuclear deal, Benjamin Netanyahu – himself tottering in office due to a corruption scandal – admonished Iran’s actions in Syria. Once Netanyahu had excited stage left, so to speak, Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif entered the fray to denounce Israel as the regional aggressor. The Saudis, another US ally which likely senses an opportunity under a Trump Presidency, then rallied against Tehran by stating that ‘[t]he world has to extract a price from Iran for its aggressive behaviour.’ As such, a move by the Trump administration to disregard the nuclear deal is likely to feed into instability in the Middle East. Moreover, given how committed other parties appear to the deal it is also likely to see power and influence seeping away from the US President.

Whether the move by the new German Coalition government to, however tentatively, distance itself from the US executive branch is a harbinger of long-term trends or a short-term response to the continually crass pronouncements of the Trump administration is currently hard to predict. Politics as usual could, of course, return if the Democrats win the presidency in 2020 or a crisis of some sort forces US allies to engage with the Trump administration in a sustained and considered manner. Moreover, if such a rapprochement was to occur, it seems likely that other US power brokers currently holding themselves up as alternative avenues for engagement may find themselves quickly sidelined. The current situation, however, demonstrates that the US’s traditional allies, unsure of the Trump administration’s reliability, are hedging their bets.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2HAcw3g

About the authors

Peter Finn – Kingston University

Peter Finn – Kingston University

Peter Finn is a lecturer in Politics and PhD candidate at Kingston University. His research is focused on conceptualising the ways that the US and the UK attempt to embed impunity for violations of international law into their national security operations. His main case study is US led detention operations during the Iraq War. His work has been published in Critical Studies on Terrorism, Open Democracy and The Conversation.

Robert Ledger – Schiller University

Robert Ledger – Schiller University

Robert Ledger has a PhD in political science from Queen Mary University of London. He has worked for the European Stability Initiative, a think-tank in Brussels, lectured at several universities in London and currently lives in Frankfurt am Main. He is a Visiting Researcher (Gastwissenshaftler) in the History Seminar at Goethe University and also teaches at Schiller University Heidelberg and the Frankfurt School of Finance & Management. He is the author of Neoliberal Thought and Thatcherism: ‘A Transition From Here to There?’