Across both the states and Congress, those who are elected often do not reflect the age, gender and ethnicity of their constituents. For many, the way that the US elects its politicians is now no longer fit for purpose. In new research, Sarah John looks at local election results in several California jurisdictions before and after the adoption of the Alternative Vote. She finds that the four California cities in the Bay Area that adopted the Alternative Vote saw an increase in the percentage of candidates of color running for office and increases in the probability of female candidates and female candidates of color winning office.

Across both the states and Congress, those who are elected often do not reflect the age, gender and ethnicity of their constituents. For many, the way that the US elects its politicians is now no longer fit for purpose. In new research, Sarah John looks at local election results in several California jurisdictions before and after the adoption of the Alternative Vote. She finds that the four California cities in the Bay Area that adopted the Alternative Vote saw an increase in the percentage of candidates of color running for office and increases in the probability of female candidates and female candidates of color winning office.

We have long known that the rules about how, when, and by whom votes are cast and counted have a good deal to do with election outcomes. American political elites have similarly long been aware that electoral rules can be used to affect whether and where minorities – both political and racial – are elected into political office. Indeed, many of the requirements of the post-Civil War Reconstruction related to the electoral system (such as mandating Virginia abandon voice voting) and one of the major outcomes of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and accompanying reforms was to outlaw the use in congressional elections of the “block vote”, a non-proportional multi-member system commonly used in the American South to prevent the election of African-American legislators.

Given the history of deploying electoral systems to curtain or eliminate the political representation of African Americans, changes in electoral law tend to be closely scrutinized in the US for any effects on descriptive representation (the extent to which lawmakers have similar characteristics like race, ethnicity, gender as their constituents).

The recent adoption of the Alternative Vote in the United States, including in cities in the California Bay Area (San Francisco and surrounds) and for the state of Maine, is no exception.

The Alternative Vote (AV) is an electoral system of many names including “ranked choice voting”, “instant runoff voting”, and “preferential voting”. It is the system that British voters rejected for the House of Commons in the 2011 Alternative Vote referendum, but is used in Australia and to elect the Irish President. AV differs from the dominant electoral systems used in the United States in that voters can rank candidates in order of preference. If a candidate wins a majority of the initial vote, that candidate wins the election. But if there is no initial majority, winners are decided by successively eliminating the candidate with the fewest votes and allocating the votes for that candidate to the candidate who is ranked next on each of those ballots until one candidate has a majority of the vote. By using the information from voters about their ranked preferences and conducting multiple rounds of counting, AV is more resistant to vote splitting and the spoiler effect than other single-member systems. It also aggregates voter preferences differently, and rewards different campaign strategies.

“Vote” by Joe Shlabotnik is licensed under CC BY NC SA 2.0

Four Californian cities have adopted the Alternative Vote since 2000: San Francisco, Berkeley, Oakland, and San Leandro. Other cities in the Bay Area, including San Jose, Alameda, Richmond and Santa Clara, have kept their plurality or majority runoff electoral system. This mix of change and staying the same in in a demographically, culturally and geographically cohesive area presents a “natural experiment”, in which it is possible to explore the effects of the change by comparing San Francisco, Berkeley, Oakland, and San Leandro against control cities in the region (including San Jose, Alameda, Richmond and Santa Clara).

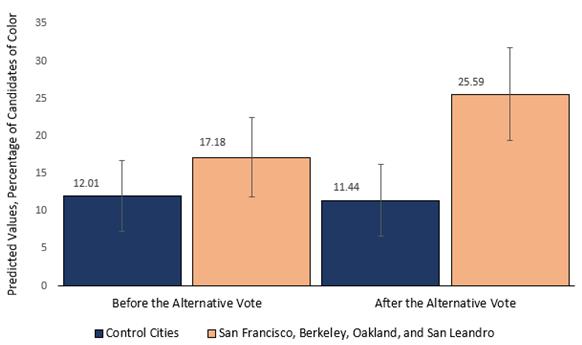

As part of our analysis, my colleagues and I examined a large database of aggregate votes for candidates for local offices as well as demographic and social variables in these eleven Californian cities covering local elections from 1995 to 2014. We found that, when other variables were held constant, the adoption of the Alternative Vote increased the percentage of candidates of color from 17.2 percent to 25.6 percent. Over the same time, the percentage of candidates of color in the control cities actually decreased slightly, from 12.0 percent to 11.4 percent (Figure 1). This effect may stem from the AV’s resistance to the spoiler effect. Under AV, multiple candidates from similar backgrounds or political views can run for the same seat without necessarily splitting the vote or playing spoiler (as vote counting proceeds, votes from eliminated candidates will be transferred to similar candidates, so long as the candidates successfully sought the second and third choices of supporters of similar candidates). There are fewer incentives for gatekeepers and community groups to limit candidacy, and fewer reasons for would-be candidates to be discouraged from running because they feel their candidacy could harm their community’s interests (by splitting the vote). AV was associated generally with more candidates running for office, but the largest increases appear to be for candidates of color, perhaps because minority communities suffer the brunt of consequences from the susceptibility of plurality and majority run-off to vote splitting.

Figure 1 – Effect of the Alternative Vote on the percentage of candidates of color

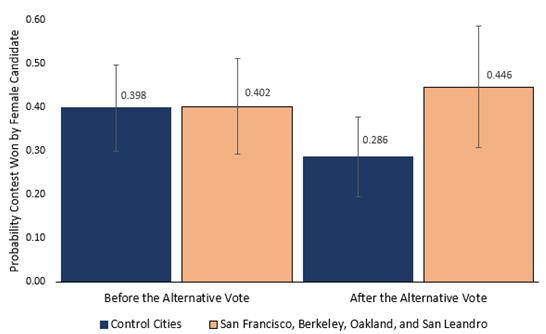

The adoption of the Alternative Vote was also associated with increased chances of women, particularly women of color, winning local elective office. When AV was adopted in local elections in the Bay Area—and other variables were held constant—the probability of a female candidate winning increased from 40.2 percent to 44.6 percent, while in the control cities the probability decreased, this time from 39.8 percent to 28.6 percent (Figure 2).

Figure 2 – Effect of the Alternative Vote on the probability of female candidate winning the election

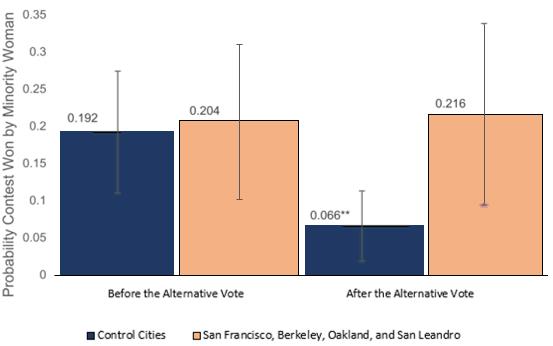

The probability of a female candidate of color winning increased from 20.4 percent to 21.6 percent when the Alternative Vote was adopted, while in the control cities the probability decreased from 19.2 percent to 6.6 percent (Figure 3). The decline in the probability of women and women of color winning in the control cities coincides with a broader national trend of decline or stagnation in the number of women elected between 2008 and 2014. Absent the adoption of AV, San Francisco, Berkeley, Oakland, and San Leandro, would likely have followed these same trends.

Figure 3 – Effect of the Alternative Vote on the probability of female candidate of color winning the election

The gains for women and female candidates of color under the Alternative Vote suggest that the Alternative Vote rewards different styles of campaigning, and styles that come more easily to women and women of color. This study cannot identify the mechanisms by which the AV increases the election of women and women of color, but the findings raise interesting questions for future research. AV, as a system that punishes negative campaigning, may advantage women’s natural (or socialized) greater aversion to negative campaigning once they become candidates. Perhaps women are more likely to campaign without negativity, and perhaps voters reward this tendency with election-winning second and third preferences. We know that among many voters, negative campaigning is not admired as a tactic. It may be that it is this same tendency to campaign positively that explains the increase in the probability of female minority candidates winning. Alternatively, women of color’s tendency to campaign to, and form, coalitions of voters (especially female voters) across different groups and identities may help explain why they win more often under AV. Perhaps women of color in the AV cities also tended to seek supporters of other candidates and supporters from different ethnic and racial groups for second and third choice support more often than other candidates.

- This article is based on John, Sarah E., Haley Smith, and Elizabeth Zack. 2018. “The Alternative Vote: Do Changes in Single-member Voting Systems Affect Descriptive Representation of Women and Minorities?” Electoral Studies 54: 90-102.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2uLNNoW

About the author

Sarah John – University of Virginia

Sarah John – University of Virginia

Sarah John is a project manager with Virginia Humanities at the University of Virginia. Previously, she was part-time faculty at California State University Fullerton and research director at FairVote, a non-partisan non-profit dedicated to electoral reform in the United States.

This is like the rooster taking credit for the sunrise.