If women run for office, they are just as likely to win an election as men. And yet, only 25 percent of state legislators are women. Samantha Pettey looks at what makes it more likely that women will run for office. She finds that while more women are running for office at the state level, those states with term limits have seen an even greater increase in the number of women candidates. The effect is even greater for Democratic women candidates, meaning that the existing gender gap in representation between the parties may continue to widen.

If women run for office, they are just as likely to win an election as men. And yet, only 25 percent of state legislators are women. Samantha Pettey looks at what makes it more likely that women will run for office. She finds that while more women are running for office at the state level, those states with term limits have seen an even greater increase in the number of women candidates. The effect is even greater for Democratic women candidates, meaning that the existing gender gap in representation between the parties may continue to widen.

In the United States, the number of women in office remains much lower than their male counterparts at all levels of government. Currently, at the state-level, female representation ranges from a low of 11.1 percent in Wyoming to a high of 40 percent in Vermont and Arizona. The average percent of females in all 50 state legislatures is only 25.4 percent. Yet, research finds that when women run for office, they are not at a disadvantage. In other words, women are just as likely to win an election as a male.

So, what makes it more likely that women will run for office? Initial research suggests term limits are not good for increasing women’s numbers in office, despite that when women run, they win. I reexamine this puzzling finding by readjusting the focus to candidate emergence and find term limits create a favorable environment for women to run in more elections. Term limits create more open seats and when there is no incumbent running, elections are theoretically easier to win. The length of terms and the nature of term limits may vary across states but one thing does not: when states have term limits, it prevents incumbents from running indefinitely. All else being equal, in terms of electoral outcomes, term limits can only be effective if the number of female candidates running within the term limited states increases.

A New Type of Candidate?

The existence of term limits does impact the number of women running for office for one fundamental reason: it changes the profile of people to whom holding state office is attractive. In states with term limits, the job is temporary and politics is not necessarily a career path. Term limits can create a pool of amateur candidates, those with no previous office-holding experience, who are motivated to run for factors other than being a career politician– especially if a potential candidate thinks they can win. A CAWP Recruitment Study finds nearly 43 percent of women in the lower chamber of the state legislatures had no previous office-holding experience; in other words, female amateur candidates are fairly common in state legislatures.

Testing the Theory of Female Emergence and Term Limits

I utilize a candidate-level dataset of election results from 1990-2010 in each state’s lower legislative chamber to examine whether or not a female candidate runs in a race. The analysis is set up as a quasi-natural experiment and looks at all general election candidates in states with and without term limits. Just like traditional experiments, there is a treatment group, states with term limits, and a control group, states without term limits. The design allowed me to not overestimate a trend in candidate emergence (or lack thereof) that may be nation-wide rather than just in term-limited states.

Term Limits Increase the Number of Women Running in General Elections

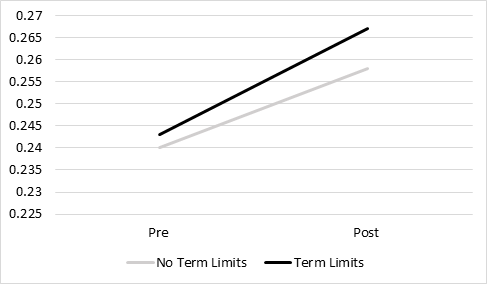

Figure 1 – Women Emergence in States Pre and Post Term Limits

As the figure shows, more female candidates emerged in all states. But, the increase in is more pronounced in states that enacted term limits. The states without term limits saw a 1.8 percent increase in female emergence post term limits (1996-2010). While the states with term limits increased female candidate emergence by 2.4 percent. As with experiments, the difference in effect size is important to note— the results show that the increase in female emergence was 33 percent larger in states with term limits.

“Women’s Caucus Breakfast” by Maryland GovPics is licensed under CC BY 2.0

While the percent seems rather small, the 0.6 percent difference, or 33 percent increase, actually equates to roughly 10 more women emerging in term limited states. For example, between 1994 and 2000, Ohio (a state with term limits), had this 0.6 percent increase. In 1996, 41 women ran for office versus in 2000, the first-year term limits took effect, 52 women emerged. And if when women run, they win, the more females emerging (even if just by 0.6 percent, or 10 females per election year), the better their chances are for increasing overall numbers in state legislatures.

Looking at the results in a different light, Figure 2 shows there are clear partisan differences. Research finds Democratic, rather than Republican women, are much more likely to be officeholders. My study supports previous research and finds term limits increase Democratic females’ emergence by roughly 2 percent and female Republican emergence by only about 1.5 percent. Further, Republican women in term limited states emerge in about 24 percent of races, versus their female Democratic counterparts who emerge 32 percent of the time in states without term limits. This means the term limit ‘boost’ given to Republican women is not enough to make them emerge as often as female Democrats not receiving the term limit boost.

Figure 2 – Female Candidate Emergence by Party

In 2018, we witnessed a record number of women running for office at all levels of government and much media attention has been given to whether this will translate into greater parity in representation. My research highlights that one way the likely gains of 2018 could be compounded or sustained is in states with term limits. However, as highlighted above, this impact is less significant for the Republican Party, contributing to an even larger gap in female representation across the two parties. Thus, to the extent that the Republican Party is interested in closing this gender gap, especially since the Party has control over many legislatures, they will need to make a concerted effort to seek out more women candidates.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Female Candidate Emergence and Term Limits: A State-Level Analysis’, in Political Research Quarterly.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2oOy9Wn

About the author

Samantha Pettey – Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts

Samantha Pettey – Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts

Samantha Pettey is an Assistant Professor of Political Science in the department of History, Political Science and Public Policy at Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts. Her research interests are a blend of gender politics and US institutions. Specifically, she is interested in how state legislatures’ institutional factors help and/or hinder women’s emergence and success in office. At the Congressional level, her research and interests focus more broadly on campaigns and elections. Her latest work appears in Political Research Quarterly and Electoral Studies.

1 Comments