In recent years, immigration has become a political football, with some American cities encouraging inflows of people from other countries while others adopt more punitive measures towards the undocumented. In new research, Matt Ruther evaluates the effects that immigrants have on urban neighborhoods that are in decline. He finds that neighborhoods with more foreign born-minorities tend to have less income losses compared to those with greater numbers of US-born minorities. In addition, areas with white or Asian immigrant groups also tend to see stable or increasing populations.

In recent years, immigration has become a political football, with some American cities encouraging inflows of people from other countries while others adopt more punitive measures towards the undocumented. In new research, Matt Ruther evaluates the effects that immigrants have on urban neighborhoods that are in decline. He finds that neighborhoods with more foreign born-minorities tend to have less income losses compared to those with greater numbers of US-born minorities. In addition, areas with white or Asian immigrant groups also tend to see stable or increasing populations.

Immigrant populations make up a substantial share of the population of most US cities, and the growth in this population is a major contributor to growth in these cities. Recent Census estimates reveal that, in 28 of the 100 largest US cities, net international migration is larger than either natural population increase or net domestic migration. Foreign-born populations are essentially keeping these cities from declining (or declining further). Although the topic of immigration is politically divisive in the US, a number of cities have nevertheless put policies in place to encourage immigrant settlement as a means to achieve urban revitalization. For example, in 2011 the city of Louisville, Kentucky instituted an Office of Globalization to better position itself as an attractive location for newly arrived immigrants. Other US cities, faced with job losses and general population stagnation or decline, have likewise embarked on ambitious plans to welcome foreign-born populations into their communities.

One premise of these policies is that the increased foreign-born population will lead to stabilization or rejuvenation of declining urban neighborhoods. However, there is little current research confirming the presence of this process. Much attention is paid to the differences in immigrant concentrations between cities – for example, Richard Florida’s creative class framework – but less attention is paid to differences within cities.

In a recent research, we looked at the effect of immigrant population growth on three broad neighborhood-level outcomes – immigrant growth, population growth, and income growth – to evaluate whether immigrant incorporation might lead to neighborhood revitalization. Although this is certainly not the first research to examine this topic, a couple of features make this updated look necessary. First, rapid growth of the US immigrant population and changes in settlement patterns and composition of this population might mean that effects that were identified prior may no longer be operating in the same way. Secondly, we wanted to stratify immigrants by broad racial categorizations (white, black, Hispanic, and Asian), to better account for the fact that the foreign-born are not a homogeneous group. And finally, we hoped to deal with the issue of endogeneity – that is, do immigrants lead to development or does development lead to immigrants? – by analyzing change over time.

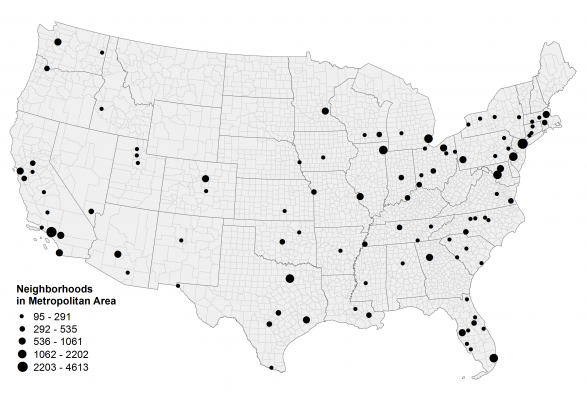

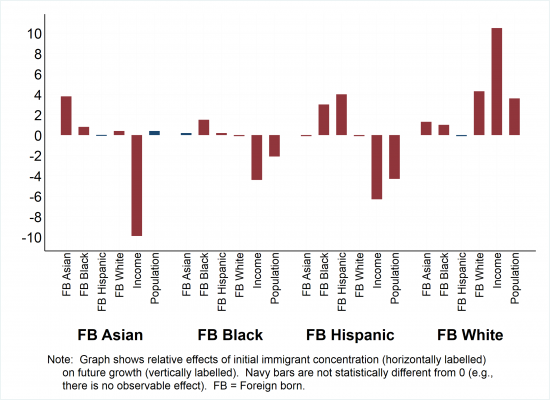

Our study looked at all neighborhoods within the 100 largest US cities as shown in Figure 1, between 2000 and 2013. Our findings, shown in Figure 2, suggest that although immigration is not a panacea for declining urban neighborhoods, immigrants may help to slow this decline or even halt it. Unsurprisingly, existing immigrant populations are predictors of immigrant growth, although this relationship varies somewhat by race. Black immigrant growth is more likely in neighborhoods with immigrant populations of any race, while Hispanic immigrant growth is more likely in neighborhoods with existing black immigrants. White and Asian immigrants are attracted to neighborhoods in which the other has a presence, but both groups are less likely to move to neighborhoods with large existing Hispanic immigrant populations. It seems clear that socioeconomic status of the immigrant group in question has bearing on these locational choices: White and Asian immigrants have, in general, higher incomes than do Hispanic immigrants.

Figure 1 – 100 largest US cities

Figure 2 – Effect of immigrant concentrations on future city growth

When we looked at the presence of US-born minority populations, we saw similar patterns of immigrant growth. As the initial share of a neighborhood population that is US-born minority increases, the share of foreign-born blacks and Hispanics increases. The share of white immigrants increases as the initial share of a neighborhood population that is US-born Asian (but not US-born black or Hispanic) increases. Foreign-born Asian populations are attracted to neighborhoods with greater concentrations of US-born Asians and to a lesser extent to neighborhoods with greater concentrations of US-born Hispanics.

The effects of initial foreign-born concentration on neighborhood population growth are small, and depend upon the race of the immigrant group in question: White and Asian immigrants are associated with population growth, while black and Hispanic immigrants are associated with population loss. However, we find no evidence that the share of the city’s minority foreign-born population within a given neighborhood is associated with income growth in that neighborhood. In fact, our findings suggest the opposite: Income growth is lower as the initial share of the black, Asian, or Hispanic foreign-born population in the neighborhood is larger. However, income growth is positively associated with the initial concentration of white immigrants.

Given the above results, it may sound surprising that we conclude that there is a positive benefit to immigrant incorporation within neighborhoods. This is because, relative to the income loss exhibited by neighborhoods with larger foreign-born minority populations, there is greater income loss shown in those neighborhoods with larger US-born minority populations. That is, the presence of immigrant populations is associated with less income loss. Overall, the groups with negative neighborhood income growth are those groups with lower socioeconomic status relative to US-born whites – notably there is no negative income association for the share of US-born Asians.

Our findings do not fully support “melting pot” theories of neighborhood growth and development, but we see them as positive verdicts for cities. Because immigrant neighborhoods attract fewer higher income residents over time, we expect to see less upward pressure on the price of housing. This would imply that the presence of immigrants might lead to less gentrification, although we do not look at displacement itself in this study. If population growth – rather than income growth – is used as the benchmark for development, Asian and white immigrant neighborhoods are redeveloping (or, at least, not declining).

Although there are certainly limitations inherent in our research – a very general definition of redevelopment, the coarse stratification of immigrant groups, a focus on all neighborhoods rather than urban core neighborhoods, and a study period that encompassed a significant recession – we hope that our study helps to compel future examination of this important topic. Given the disinvestment that has occurred in US cities over the past several decades, these types of positive outcomes should be celebrated.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Foreign-born population concentration and neighbourhood growth and development within US metropolitan areas’, in Urban Studies.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2IE8gl8

About the author

Matt Ruther – University of Louisville

Matt Ruther – University of Louisville

Matt is an Assistant Professor of Urban and Public Affairs at the University of Louisville. His research focuses on population estimation and forecasting, neighborhood growth and change, and spatial methods and analysis.