Walls have very much been in the news of late, with President Trump pushing for a “big, beautiful wall” on the border with Mexico to prevent the entry of undocumented immigrants. But not all walls are inherently bad, writes William A. Callahan. Using China’s Great Wall as an example, he argues that we need to understand them as gateways rather than barriers. The real issue is who controls the flows through these gateways, and to what end.

Walls have very much been in the news of late, with President Trump pushing for a “big, beautiful wall” on the border with Mexico to prevent the entry of undocumented immigrants. But not all walls are inherently bad, writes William A. Callahan. Using China’s Great Wall as an example, he argues that we need to understand them as gateways rather than barriers. The real issue is who controls the flows through these gateways, and to what end.

- Bill Callahan’s short film, ‘Great Walls: Journeys from ideology to experience’ will be screened on 2 March 2019 at LSE as part of the LSE Festival: New World (Dis)Orders. More information and tickets.

As Donald Trump’s anti-immigration policies illustrate, walls are a hot topic. While ‘globalization’, with its free flow of capital and goods, characterized world politics after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the 21st century has witnessed a reassertion of cultural, legal, and physical barriers. It is common to criticize

post-Cold War walls like Trump’s desired US-Mexico barrier not only as ineffective, but as immoral. In response to Trump’s call for “a big, fat, beautiful wall!”, Pope Francis declared building walls morally repugnant, while building bridges is the ‘Christian’ way.

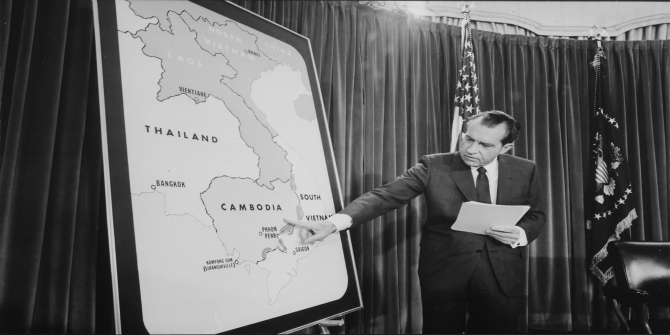

This critique of border walls as ineffective barriers that exclude vulnerable people on immoral grounds is compelling. That is, until you consider the example of the Great Wall of China, which is praised around the world as an achievement of civilization: Mao Zedong told his compatriots “You aren’t really a hero until you’ve climbed the Great Wall”, while Richard Nixon told the world “This is a great wall and it had to be built by a great people”.

Wall-building here is not seen as a crime against humanity. Rather, it is a basic human endeavor: as classical Chinese philosopher Xunzi explains, “Wherein lies that which makes humanity human? I say it lies in humanity’s possession of boundaries.”

While discussion of the politics of border walls is dominated by dark memories of the Berlin Wall and outrage over Trump’s new wall, the Great Wall can help us rethink the issues. While Trump’s wall aims to be an absolute sovereign barrier, the Great Wall actually was never such a continuous wall along a single-line boundary. Rather, there are dozens of discontinuous and overlapping walls, built at different times, by different peoples, for different purposes: some were defensive against outsiders, but others were built to secure newly-conquered territory. Rather than see this discontinuous wall as a weakness, we should look to its gaps as opportunities for critical reflection.

Photo by Puk Khantho on Unsplash

Certainly, my point is not that walls are ‘good’ rather than ‘evil’. Rather, what the Great Wall of China teaches me is that we need to challenge the political piety of both conservatives and progressives because such moral posturing tends to close down discussion. Walls, like most things, are complex sites that can be good or ill—or even morally ambiguous. The point is not to either close or open borders, but to examine the ethical questions of who controls the flows, and to what end.

Figure 1 – Immigration counter at Haikou International Airport, China (2016)

Source: William A. Callahan

Thus, rather than understand walls as barriers that separate countries, it is helpful to understand them as gateways that can connect them. Alongside its work as military architecture, the Great Wall was a site of meeting and exchange, where China and its Northern neighbors fostered peaceful relations through trade: nomadic pastoralists exchanged horses for Chinese grain, metalwork, and handicrafts (see Figure 1). Indeed, gateways (usually minus the walls) are enduring cultural sites in contemporary East Asia and beyond: the Gate of Exalted Ceremonies (Sungnyemun) in Seoul is a powerful identity site for Koreans; many of Beijing’s subway stations are named after the gateways of the long-dismantled city wall; and gateways define Chinatowns around the world (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 – Dragon Gate, Chinatown, San Francisco

Credit: chensiyuan [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Hence instead of functioning as absolute barriers, the Great Wall suggests that we appreciate how walls work as contact zones: sites of markets and exchange where entry and exit are managed at the gateway. While contemporary critics see walls as a moral problem of clear divisions, where all selves are xenophobic in their division from the Other, attention to flows at the gateway shows how the power, unity and even morality of the wall is produced at its gaps. The wall is not a simple moral outrage; rather it is a new economic and political opportunity that has been provoked by a recalibrated dynamic of flows of capital, goods, ideas, and people. As the Great Wall shows, rather than be distracted by its awesome battlements, we should pay attention to the flows through its gateways.

We need to get away from the urge to either praise walls as ‘good’ or denounce them as ‘evil’. Rather than argue over whether to close or open borders, it is necessary to examine the ethical questions of who controls the flows, and to what end. Here, walls are interesting precisely because their political and social meaning is complex—and unpredictable. China’s most famous modern writer Lu Xun thus concluded that the Great Wall of China is both “a wonder and a curse”.

- This article is based on the open access paper ‘The politics of walls: Barriers, flows, and the sublime’ in the Review of International Studies.

- Featured image credit: William A. Callahan

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2N4Kdhw

About the author

William A. Callahan – LSE International Relations

William A. Callahan – LSE International Relations

William A. Callahan is professor of international relations at the London School of Economics and Political Science. His most recent book is China Dreams: 20 Visions of the Future, and this article is taken from ‘The Politics of Walls: Barriers, Flows, and the Sublime’. Callahan is also a documentary filmmaker: his current project ‘Great Walls’ will be screened in London at the LSE Festival on March 2, 2019 and in Denver at the Association for Asian Studies annual conference on March 25, 2019.