The harsh enforcement practices surrounding and extending from the US-Mexico border have prompted widespread criticism from activists. But how else are the US government and local authorities attempting to dissuade potential migrants? Jill M. Williams takes a close look at more than two decades of public information campaigns aimed at convincing those from other countries from making the journey to cross the border. She writes that these campaigns – which are now a multi-million dollar industry – rely on the wide distribution of emotive imagery to encourage potential migrants to question whether the benefits of making the journey are worth the potential costs.

The harsh enforcement practices surrounding and extending from the US-Mexico border have prompted widespread criticism from activists. But how else are the US government and local authorities attempting to dissuade potential migrants? Jill M. Williams takes a close look at more than two decades of public information campaigns aimed at convincing those from other countries from making the journey to cross the border. She writes that these campaigns – which are now a multi-million dollar industry – rely on the wide distribution of emotive imagery to encourage potential migrants to question whether the benefits of making the journey are worth the potential costs.

When it comes to increasingly punitive measures to control migration the United States is proving itself to be a world leader. In just the last few months, humanitarian aid workers were brought to trial for providing migrants with food, water, and shelter; massive work-place raids targeting undocumented workers were carried out in Mississippi, resulting in the detention of nearly 700; and the federal government has taken dramatic moves to limit Central Americans’ rights to claim asylum. Meanwhile, efforts are underway to divert millions of federal tax dollars away from health and education to fund the expansion of the border wall along the southern border of the US—a project that has received widespread criticism from migrant and environmental activists alike.

While much public and political attention rightly focuses on border enforcement efforts that criminalize unauthorized migration and militarize border regions, a lesser-discussed approach to border enforcement targets the emotional lives of migrants in an attempt to influence decision-making and dissuade potential migrants from attempting to make the trip.

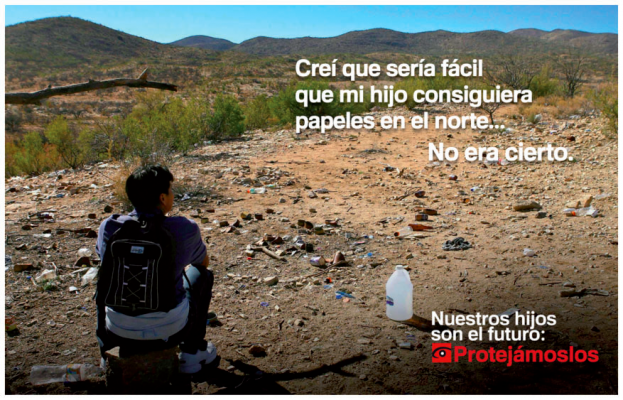

Public information campaigns (PICs) have been used by US border enforcement agencies since the early 1990s. Unlike hard power strategies that use guns, walls, and imprisonment to control migration, PICs use the strategic spreading of emotion-laden messages to dissuade migration attempts.

First launched in the Border Patrol’s Tucson Sector, early campaigns were low-budget, low-tech, and painfully graphic. Small groups of Border Patrol agents pooled personal resources and diverted funds from other projects to produce flyers showing the decomposing bodies of dead border crossers alongside statistics on the impossibility of carrying enough water to survive an extended desert crossing. Materials were distributed in migrant shelters, cheap hotels, and restaurants in the border towns of Nogales and Agua Prieta, Sonora.

By the early 2000s, public information campaigns were adopted agency wide and a public relations firm out of Washington, DC was contracted to produce a multi-million dollar, multi-year campaign. Entitled No Más Cruces en la Frontera, this campaign targeted the emotions of potential migrants and their family members through a wide variety of modes including songs, television announcements, mini documentaries, and print campaigns. Campaign materials often highlighted the personal stories of families whose loved ones died during migration attempts. Images of grieving and crying mothers, wives, and children were common, all working to counter the very real economic, political, and social factors that compel individuals to embark on long and arduous migration attempts.

Collaborations with mass media networks and governmental and non-governmental organizations have enabled campaign materials to reach deep into the spaces of everyday life in migrant communities. In the early 2000s, CDs of migracorridos (migration ballads) were distributed to radio stations throughout Mexico and in US cities with large populations of migrants, eventually playing on over 21 radio stations. Death, kidnapping, and sexual violence were central features of the ballads that aimed to discourage migration by raising awareness of the risks.

Beginning in 2011, campaigners expanded their distribution networks beyond mass media. Collaborations were developed with the Latin American Institute for Educational Communication in order to embed campaign materials into the educational curriculum distributed by the institute throughout Mexico and Central America. Non-profits, governmental organizations, and churches were also approached as campaign distributers worked to embed campaign messages into the everyday spaces where potential migrants and their loved ones lived and socialized—restaurants, schools, homes.

Since the 1990s, the target audience of campaigns has shifted from almost exclusively focusing on male migrants to also targeting female migrants and the families of migrants—a reflection of the shifting demographics of transnational migration and the states desire to stem the tide of migrant families and unaccompanied minors. Narratives of sexual violence and the deaths of young people are used to encourage potential migrants and the family members who finance their journeys to question if the potential benefits of migration are worth the potential costs.

For over a decade, political geographers have drawn attention to the spatial expansion of border enforcement efforts and what it means for those who migrate. Collaborations between local and state law enforcement and federal border enforcement agencies mean that seemingly banal events such as a traffic stop can lead to detention and deportation. At the same time, binational agreements between the US and foreign governments, such as Mexico and Guatemala, create a situation in which US border enforcement objectives—stopping migrants before they reach the southern border—are carried out on foreign soil, by foreign actors.

“Border Crossing 2.5 (San Ysidro)” by U.S. Customs and Border Protection is US Government.

Public information campaigns are yet another way in which border enforcement efforts are extended into spaces far from the literal border. Campaign materials seep into the daily lives of individuals and communities as they go to school, socialize, and simply live their lives. Strategically crafted messages aim to compel emotional responses—fear, guilt, sadness, distrust—responses strong enough to overcome the powerful factors driving migration.

PICs are not unique to the US. Since the early 2000s, PICs have been used by a wide variety of countries in the global North including Belgium, the Czech Republic, Australia, and Italy. However, they remain relatively unexamined in both academic and policy circles.

While spectacular border enforcement strategies such as workplace raids that leave children without parents and high-tech fences garner much public and political attention, PICs represent a softer, but no less relevant, side of border enforcement in the 21st century. Further inquiry into PICs is necessary for helping researchers and policy makers understand the complexity of border enforcement today.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Affecting migration: Public information campaigns and the intimate spatialities of border enforcement’ in Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/31XX7UV

About the author

Jill M. Williams – University of Arizona

Jill M. Williams – University of Arizona

Jill M. Williams is an Associate Research Professor in the Southwest Institute for Research on Women and affiliate with the School of Geography and Development at the University of Arizona. Her research uses feminist theoretical and methodological approaches to examine contemporary border enforcement efforts and their impact on human rights, transnational mobility, and state sovereignty.