In recent decades, the Supreme Court has been seen as increasingly as a political as well as a legal institution, with justices’ partisan ideologies informing their decision-making. In new research, Kayla Canelo examines how justices reference and cite friend-of-the-Court or amicus curiae briefs from interest groups in their majority opinions. She finds that justices are more likely to borrow language from interest group briefs which are ideologically closer to their own interests, and is likely to go unnoticed, but are less likely to directly cite these briefs, potentially to protect their own legitimacy in the public’s eye.

In recent decades, the Supreme Court has been seen as increasingly as a political as well as a legal institution, with justices’ partisan ideologies informing their decision-making. In new research, Kayla Canelo examines how justices reference and cite friend-of-the-Court or amicus curiae briefs from interest groups in their majority opinions. She finds that justices are more likely to borrow language from interest group briefs which are ideologically closer to their own interests, and is likely to go unnoticed, but are less likely to directly cite these briefs, potentially to protect their own legitimacy in the public’s eye.

The Supreme Court is both a legal and political institution. While there are many examples of this dual role, a prominent one in political discourse today pertains to Justice Stephen Breyer. Breyer recently wrote a book claiming the Supreme Court is above politics and must remain this way to protect the legitimacy (or image) of the institution. However, the past few Supreme Court nominations have been highly contentious, and some are calling on Breyer to retire so President Biden can replace him with another liberal, highlighting the ideological component of Supreme Court decision-making.

One way to assess how the Supreme Court justices balance policy goals and legitimacy concerns is to examine how they interact with some of the most political entities around— interest groups. A plethora of organized interests file friend-of-the-Court (amicus curiae) briefs to provide the justices with information and to encourage them to vote a particular way in a case. These filings have been increasing in number over time and the justices have been using these briefs to help craft their majority opinions.

Specifically, the justices at times reference these groups explicitly in their majority opinions while at other times they borrow the exact language from these briefs, often without attribution. These two types of uses are different in that one (citing) is visible to the reader while the other (borrowing language) is not noticeable. As such, borrowing language might provide opportunities for the justices to engage in ideological behavior by relying on information from ideologically similar groups. However, if justices are concerned with legitimacy, they might be more cautious of the groups they decide to formally cite.

Fortunately, scholars have gathered data on all amicus curiae filings from 1953 to 2013 and produced the ideological locations (known as ideal point estimates) for 600 organized interests in the same policy space as the Supreme Court justices. This allows researchers to compare how the ideological preferences of the interests compare to those of the justices. In my research, I assess whether the justices borrow more language from ideologically similar interests (to advance their policy goals) and whether they are less likely to cite ideologically overt interests (to protect their own legitimacy).

Do justices rely more on briefs filed by ideologically similar interests?

First, I started by looking at borrowed language. I collected friend-of-the-Court briefs filed by organized interests in 300 randomly selected cases from the 1988-2008 Supreme Court terms. To assess the amount of language the majority opinion borrowed from these briefs I ran them through plagiarism detection software called WCopyfind. This produced the percentage of the majority opinion derived from language from each individual brief.

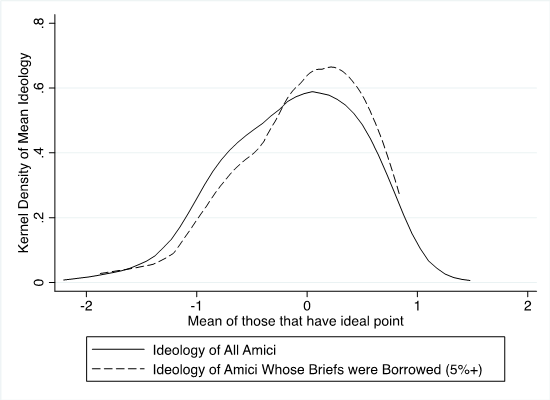

Figure 1 shows the ideological locations of the briefs (i.e., the locations of the groups or interest(s) that filed the brief). This is on a typical left-right scale where negative values represent what is conventionally viewed as liberal and positive values represent what is conventionally viewed as conservative. The solid line represents all the briefs in the dataset, while the dashed line depicts the briefs where 5 percent or more of the majority opinion’s language was derived from said brief. As evident in the figure, the justices borrow language from a wide range of interests, ranging from approximately -1.8 to 1.

Figure 1 – Ideology of interests on briefs (borrowed language data)

I used multivariate analysis to determine whether the justices borrow more language from briefs filed by interests that are ideologically similar to their own preferences. I find that the more ideologically aligned the opinion writing justice is with the interests on the brief, the more language the justice will borrow in their opinion.

“Equal Justice Under Law” (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) by afagen

Next, I assessed whether the justices are cautious with the types of interests they cite to safeguard their legitimacy. While many friend-of-the-Court briefs are filed, very few are cited. As such, I had to intentionally select cases where a brief was cited in the majority opinion and use a statistical package called ReLogit that accounted for biases that this might introduce. This data collection ultimately produced 3,297 briefs filed in over 500 cases. I have ideological data for 1,935 of those briefs which were used in the analysis.

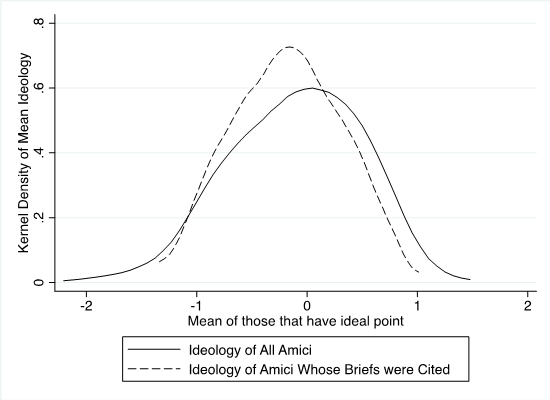

Figure 2 represents the ideological locations of the briefs (i.e., the locations of the interest(s) that filed the brief). The solid line represents all of the briefs in the citations dataset. The dashed line represents the ideological locations of the interests whose briefs were cited in the majority opinion. What is different from the first figure is that while the justices borrow language from briefs filed by more ideological interests (particularly on the left ranging from -1 to around -1.8) this isn’t replicated when it comes to citations. Rather, the justices cite interests that are near the -1 to 1 range, which is where the bulk of the briefs are located.

Figure 2 – Ideology of interests on briefs (citations data)

I used multivariate analysis to determine whether there was a relationship between ideology and the decision to cite. I did not find that the justices avoid citing briefs the more ideological they are. However, I did find that the justices are less likely to cite the most unapologetically ideological groups (those in the tail ends of Figure 2). This suggests there might be some legitimacy component at play in the decision to cite amicus briefs. Interestingly, I did not find that the justices cite briefs filed by ideologically similar interests, contrary to what was found in the analysis on borrowed language.

Justices borrow more language from briefs filed by ideologically similar groups, but citations are more complicated

It does not appear the justices engage in the ideological use of amicus briefs when it’s in plain sight, as I did not find that the justices are more likely to cite briefs filed by ideologically similar interests. But they do engage in such behavior when it is out of view, borrowing more language from briefs filed by interests who are ideologically similar. Further, I do not find that the justices avoid citing briefs filed by ideological groups, but they are less likely to cite briefs filed by the most unapologetically ideological groups. Taken together, these results suggest the justices engage in ideological behavior when it is likely to go unnoticed, but also hold some level of concern for how their opinions and/or the institution are perceived by the public.

These findings open the door to future lines of research. Researchers should next analyze the text that is being borrowed to determine what type of information the justices are taking from friend-of-the-Court briefs. Further, given the increasingly partisan nature of the Court, I’m currently working to examine more recent Court terms to assess whether ideology is playing a more central role in the decision to cite in this context and whether dissenting opinion authors use citations in response to the majority.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘The Supreme Court, Ideology, and the Decision to Cite or Borrow from Amicus Curiae Briefs’, in American Politics Research.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/2Zk5IoJ

About the author

Kayla S. Canelo – University of Texas at Arlington

Kayla S. Canelo – University of Texas at Arlington

Kayla S. Canelo is an assistant professor of political science at the University of Texas at Arlington. She studies American politics with a focus on judicial politics and public opinion. Her research has been published in the Journal of Politics, State Politics and Policy Quarterly, Presidential Studies Quarterly, and American Politics Research.