Immigrant groups often face discrimination in daily life across a wide variety of social, cultural and economic situations. In new research Vasiliki Fouka examines whether this discrimination is caused by a lack of integration or if integration itself is restricted by discrimination. Using the experience of German Americans during World War I, she finds that in the face of a wave of discrimination, the group pushed even harder to be accepted into US society through measures like adopting more ‘American’ style names and increased citizenship petitions.

Immigrant groups often face discrimination in daily life across a wide variety of social, cultural and economic situations. In new research Vasiliki Fouka examines whether this discrimination is caused by a lack of integration or if integration itself is restricted by discrimination. Using the experience of German Americans during World War I, she finds that in the face of a wave of discrimination, the group pushed even harder to be accepted into US society through measures like adopting more ‘American’ style names and increased citizenship petitions.

Immigrants and members of ethnic minorities experience discrimination in a variety of settings. Job applicants with immigrant sounding names have a lower chance of receiving callbacks for job interviews and candidates of immigrant origin are less likely to be included on electoral lists by party gatekeepers. A high percentage of immigrants reports having experienced discrimination in daily life in both the US and Europe.

Such discrimination tends to go hand in hand with lack of integration, meaning that immigrants have not been fully accepted into social, economic and cultural aspects of society. For example, across a number of European countries, perceptions of discrimination are positively correlated with the gap in unemployment rates between immigrants and natives. One question that arises is then: does the lack of integration invite discrimination on the part of native-born populations? Or is discrimination instead the cause, rather than the consequence of low immigrant integration? Given there exists a feedback mechanism between discrimination and integration, these questions are hard to answer empirically.

In recent research, I use a natural experiment from the history of the United States to provide causal evidence on the effect of discrimination on immigrant integration. During World War I, German Americans, the country’s then largest immigrant community, became the targets of discrimination and societal harassment. This wave of anti-Germanism was spurred by the war and had nothing to do with the Germans’ degree of integration in US society. I find that, in response to this targeting, immigrants did not retreat from society, but instead did everything they could to reaffirm their belonging.

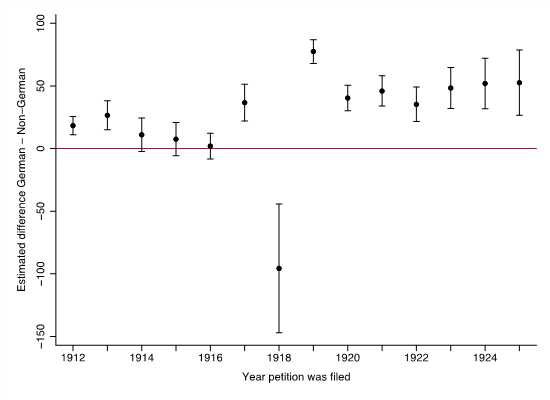

To measure immigrant efforts to integrate politically and socially, I use archival data and historical census records. I construct counts of petitions for naturalization filed by immigrants in a number of US states between 1911 and 1925 from digitized naturalization records available online. I compare the number of petitions filed by German immigrants to those filed by other nationalities over time. Figure 1 shows that after the US entered WWI in 1917, the number of petitions filed by Germans increased relative to petitions filed by other immigrant groups.

Figure 1 – Difference in number of naturalization petitions filed by year, German immigrants vs others

Source: Naturalization records of California, Maryland, Pennsylvania and Virginia. All foreign-born non-enemy aliens who enlisted in the US Army in 1918 were made citizens immediately upon the filing of their naturalization petitions, which explains the large drop in 1918.

At the same time, the number of German naturalization petitions that became accepted by the courts dropped during WWI, as courts intentionally delayed the processing of those petitions, resulting in lower rates of citizenship acquisition among Germans. Discrimination reduced rates of political belonging for German immigrants, but this was not because of their retrenchment. Rather, it was despite their increased efforts to claim membership into US society.

“[NYC police] fingerprinting a German [1917] (LOC)” by The Library of Congress has No known copyright restrictions, Call Number: LC-B2- 4482-14a

In additional support of the claim that Germans increased their efforts to assimilate in response to discrimination, I examine naming patterns. I digitize the content of over 3,000 petitions filed by immigrants in two district courts in Illinois and Pennsylvania. The information recorded on the petitions includes the name of each petitioner at the time of the petition, as well as the name they had upon arrival in the country. After the outbreak of WWI, Germans became more likely than other immigrant groups to Americanize their first and last names.

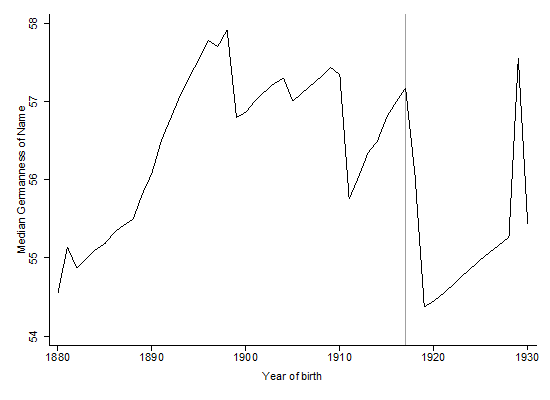

Investment in assimilation extended to immigrants’ offspring. I use information on the naming choices of millions of individuals observable in historical US censuses to create a measure of how distinctive a first name is of a given nationality. Figure 2 shows that the names of children born to German parents after 1917 were less likely to be characteristically German than those of older cohorts.

Figure 2 – Index of name Germanness of second-generation German men, by year of birth

Source: 1930 US Census and author’s calculations.

One may worry that this finding is due to the least assimilated Germans leaving the country, but this is not the case. German children born after the war had more American names compared to their older siblings born just before the war. This means that families changed their decisions in response to anti-Germanism.

How can we be sure that attempts of German immigrants to visibly demonstrate assimilation were responses to native hostility against them? Several pieces of evidence point to this conclusion. Parents were more likely to Americanize their children’s names in states in which Germans experienced more public harassment, as measured by the frequency of mentions of anti-German violence in local newspapers. I also rule out alternative explanations for the observed pattern. For example, the behavior of German immigrants was not due to the fact that they could no longer hope to repatriate one day to Germany. Immigrants from countries that remained neutral during WWI, such as Norway, also ended up experiencing harassment during the war. Just as the Germans did, those groups also Americanized their children’s names after 1917.

To what extent do findings from this historical context generalize to immigrant behavior today? After all, Germans were a relatively well integrated group in the early 20th century US. Would groups that are visibly different or culturally and religiously distant to the host country’s majority population exhibit similar reactions to discrimination? My findings indicate that the level to which immigrants tried to assimilate is linked to how integrated they were to begin with. Name Americanization was more pronounced among Germans more embedded in US society; those who had lived for longer in the US or who were already US citizens. Less well-integrated subgroups did not respond with assimilation, but neither did they show strengthening of German identity in response to harassment.

My research can inform current debates on minority reactions to discrimination. With the share of the foreign-born representing more than 10 percent in the US and in countries of Western Europe such as Germany and France, there is a growing concern that native prejudice ends up alienating a large share of those countries’ population. Discrimination could discourage immigrants from investing in integrating in the host country and drive them instead to retreat into their ethnic communities.

The main takeaway from my work is that such concerns may be overstated. Reaction and alienation are not the average responses among immigrant populations. While nobody endorses discrimination, the German-American case shows that even in the face of harassment, the biggest driver of immigrant decisions is the desire to belong.

A second important takeway is that the positive correlation between perceptions of discrimination and indices of social and economic integration is not due to discriminated immigrants giving up on their efforts to integrate. Integration is a two-sided process that requires acceptance from the host society and investment on the part of immigrant groups. The case of German-Americans during WWI indicates that higher levels of discrimination can negatively affect integration, despite immigrants’ increased integration efforts.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘How Do Immigrants Respond to Discrimination? The Case of Germans in the US During World War I’ in American Political Science Review.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/322rLfu

About the author

Vasiliki Fouka – Stanford University

Vasiliki Fouka – Stanford University

Vasiliki Fouka is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at Stanford University. She earned a PhD in Economics from Pompeu Fabra University. She studies group identity and ingroup-outgroup relations with a focus on immigrant assimilation. Her work is published or forthcoming in the American Political Science Review, the Review of Economic Studies and the Journal of Politics.

Even when you look the same…there still ban be distrust,hate and discrimination levied against you as an immigrant.The Anglo’s are the Irtish,and the Saxons are the Germans.The two groups are closely related and look very much alike.However,when immigrant German farmers and unskilled laborers began to arrive at the late 1800’s to America…the status-quo of Anglo-Americans saw them as crude,too foreign and an unassimilable threat..They did bot speak English,many were Catholics and most were uneducated.Simply being white and even Northern European did not stop the hysteria against them initially in the complicated history of immigration to the U.S.

Thank you for your fantastic scholarly report. To my fellow Americans that would deny, and many with hate, the immigration of Mexican people, I counter with several points to consider: Attempt to assimilate into ANY culture outside of the U.S. (not including Canada). An understanding and empathy toward immigrants quickly develops, in consideration of the fact that people of Mexico risk DEATH, just for the CHANCE to live in America. To patriots who rally only for America, its Constitution, the protections and freedoms therein, and with ugly battle cries, who seek to prevent and exclude Mexican immigration, I say, examine your own heritage. America is not a race, a tribe, or a union of ONE people. I vehemently remind you that the MAJORITY of Mexican immigrants do all kinds of nasty backbreaking work that the majority of Americans refuse to do, such as in the slaughterhouses, that provide us with those “millions and millions” of hamburgers, our pet’s food, our high end steak houses, our BBQs and oir lunchmeats . If all of Mexican people were suddenly forced to repatriate to Mexico, America would SHUT DOWN OVERNIGHT. A possible solution is a ZERO tax system for all, with only SALES TAX on purchases at varying percentage rates. Everyone should be welcomed, and everyone should pay taxes. The volatilty toward immigrants and the disparities in wealth seem to be root causes against immigration.