Despite its design as a deliberative body, the United States Senate has become a place of legislative gridlock, with party leaders often resorting to procedural moves to pass legislation. In new research, Neil S. Chaturvedi looks at the use of the ‘filling the amendment tree’ tactic in recent Congressional sessions. He writes that while the tactic, the use of which was accelerated by the then Democratic Senate Majority Leader, Harry Reid (NV), may have helped to get legislation passed, it also may have harmed more moderate Democrats’ reelection chances, which in turned helped to polarize the chamber even further.

Despite its design as a deliberative body, the United States Senate has become a place of legislative gridlock, with party leaders often resorting to procedural moves to pass legislation. In new research, Neil S. Chaturvedi looks at the use of the ‘filling the amendment tree’ tactic in recent Congressional sessions. He writes that while the tactic, the use of which was accelerated by the then Democratic Senate Majority Leader, Harry Reid (NV), may have helped to get legislation passed, it also may have harmed more moderate Democrats’ reelection chances, which in turned helped to polarize the chamber even further.

Once thought of as the “world’s greatest deliberative body,” the United States Senate has increasingly become a partisan one in which members have steadily moved to the poles of their respective parties. Indeed, the Senate may not be as deliberative as it is undemocratic. Over the past twenty years, the minority party’s use of the filibuster, a procedure in which the minority party can delay a vote on legislation indefinitely and requires a supermajority of 60 votes to overcome, has exacerbated the gridlock within the chamber. Beyond this, the minority party has also employed the use of “poison pill amendments,” or amendments proposed to a bill whose sole purpose is to make voting on the bill difficult for vulnerable members of the majority party.

To combat this, former Democratic Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid employed a rarely used tactic called, “Filling the Amendment Tree.” According to Senate procedural rules, any senator can propose an amendment, regardless of content (with only a few rare exceptions). However, the process is structured to allow for a sequence of amending. For example, an amendment that changes the language in a bill would be considered before an amendment that strikes the language. To organize this, the Senate Parliamentarian diagrams the amendments into a tree formation in which slots are allotted to each proposal. Most bills are limited to how many amendments can fill the amendment tree.

The Majority Leader enjoys the right of first recognition, and as such, Reid would fill every branch with amendments that would nominally change the bill or would propose amendments and then propose secondary amendments to remove the language of the initial proposal. This made it so that no one could propose any amendments to the bill and the integrity of the bill would remain unaltered. If the majority party could overcome any filibuster efforts, the bill could pass the Senate as the majority party intended it to, without any changes to the overall language of the bill. The procedure is not without merit. Indeed, if the majority party has a clear policy proposal that they desire and are fundamentally agreed on, they could ensure that these proposals are passed. Such levels of party control are rare in the Senate and typically reserved for the House of Representatives, where, generally, only a simple majority is needed for legislation to pass. Furthermore, it prevents vulnerable moderates within the party from taking difficult votes that could be used against them as campaign fodder in future elections.

Still, while the amendment tree prevents members of the minority party from offering poison pill amendments, it also prevents members of the majority party from offering any amendments as well. This is especially important in the Senate, where senators are less reliant on party branding, especially those that come from states that are hostile to the majority party (see, for example, Joe Manchin from West Virginia during Democratic majorities or Susan Collins from Maine during Republican majorities). While the intentions of the procedure may be to shepherd the bill to passage and protect vulnerable moderates, it may take away these same members’ ability to distinguish themselves from their party.

“US Capitol” by Mark Fischer is licensed under CC BY SA 2.0

Undeniably, the effects of the procedure on public policy are clear as it allowed the Senate Democratic majority to pass several bills without the minority party’s obstruction with amendments. Though what is unclear is what impact this had on the membership of the majority party. In new research, I examined every instance in which Harry Reid filled the amendment tree during the 111th through the 113th Congresses. Those Congresses are of interest because the 111th Congress is the first year in which Democrats controlled the House, Senate, and Presidency, and the 112th and 113th Congresses had the Democrats in control of the Senate and the presidency. I searched the Congressional record for instances in which Reid was the only senator to officially be recognized for his proposals. As expected, whenever this was the case, Reid’s proposals negligibly changed the bill (i.e. changing a date and then changing it back). In all, there were 25 instances in which Reid filled the amendment tree in these three Congresses.

I was interested in two things. First, the procedure prevents senators from officially having their amendment recognized. It does not, however, prevent senators from proposing amendments, which are recorded in the Congressional Record. As such, I was interested to see who was being shut out of the amendment process. If the process is to protect vulnerable moderates, we should see few, if any vulnerable party members propose amendments on the majority side. Second, I was interested in the overall effect the procedure had on the voting records of individual senators, particularly vulnerable moderates who would have to defend their voting record in subsequent elections.

I found that on balance, Republicans proposed more amendments than Democrats. Specifically, ideology was a strong predictor for who would propose amendments for Republicans, with ideologically polarized Republicans proposing more amendments than their more moderate counterparts. For Democrats, there was no statistically significant relationship between ideology and the proposing of amendments. This suggests that moderate Democrats did not use the amendment process to distinguish themselves from their party.

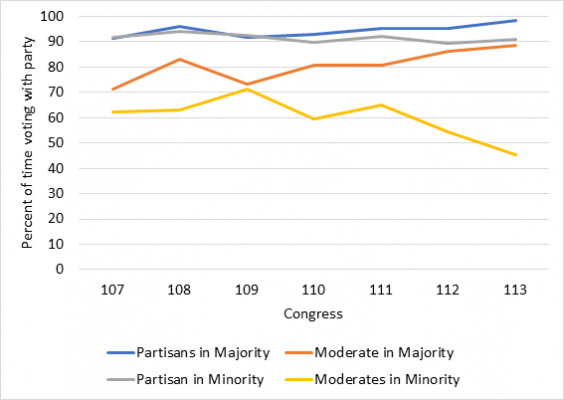

Still, when I examined voting records, there is some evidence to suggest that Reid may have done some damage to the electoral prospects of many senators. In Figure 1 below, I illustrate party unity scores from the 107th to the 113th Congress. We should see moderate senators diverge from their more ideological counterparts, and indeed, for much of the time, we do. However, there is a clear uptick immediately after the 110th Congress in which moderate voting records begin to resemble more ideological voting records.

Figure 1 – Party Unity Scores for the 107th-113th Senates for Majority and Minority Members

Source: Keith Poole and Howard Rosenthal’s voteview.com. Moderates are calculated as the 15 senators closest to “0” on the DW-Nominate 1st Dimension score.

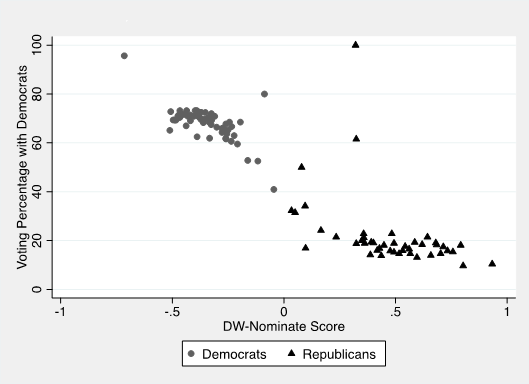

When I isolate the voting records to reflect only the bills in which Reid filled the amendment tree, we see why this agreement begins. In Figure 2 below, I show the voting records of Democrats and Republicans by ideology for the 111th Congress. The figure looks as we would expect, for the most part, in which liberal Democrats were most loyal to their party and conservative Republicans were most loyal to their party, with moderates falling somewhere in between.

Figure 2 – Voting records on Amendment Tree Bills (111th Congress)

*Note: these voting records reflect only votes on bills in which the amendment tree was filled.

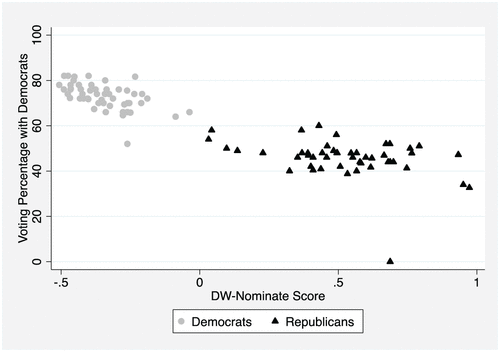

However, in subsequent Congresses, the voting records for the Democratic Caucus becomes more similar. In Figures 3 and 4 below, moderates are markedly less spread out in terms of their partisanship. Specifically, in the 112th Congress, we see much of the caucus clustered around the 70-80 percent range with only a handful of senators below that and only one senator at the 50 percent range. In the 113th Congress, every Democrat is voting with their party at a rate above 80 percent on bills in which Harry Reid filled the amendment tree.

Figure 3 – Voting records on Amendment Tree Bills (112th Congress)

Figure 4 – Voting records on Amendment Tree Bills (113th Congress)

*Note: these voting records reflect only votes on bills in which the amendment tree was filled.

Statistical analysis confirms that the difference between moderate and non-moderate Democrats shrank from a statistically significant difference of 8.3 percent in the 111th Congress to a statistically insignificant 1.6 percent by the 113th Congress, making moderates indistinguishable from their more ideological counterparts.

This suggests that while Reid may have ushered through many Democratic Party preferred bills in his time as Senate majority leader during the Obama administration, it did not come without cost. Specifically, the more similar voting records of moderate senators and a more polarized Senate, opened moderates to attacks of being too liberal or partisan, complicating their reelection campaign message. Indeed, after the 113th Congress, Republicans retook control of the chamber after the defeats of Democratic moderates, Mark Begich (AK), Mark Pryor (AR), Mark Udall (CO), Mary Landrieu (LA), and Kay Hagan (NC). Moreover, these moderates were then replaced by more ideologically polarized Republicans, further polarizing the chamber.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Filling the Amendment Tree: Majority Party Control, Procedures, and Polarization in the U.S. Senate’ in American Politics Research.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2ONZG83

About the author

Neil S. Chaturvedi – California State Polytechnic University

Neil S. Chaturvedi – California State Polytechnic University

Neilan S. Chaturvedi is an assistant professor of political science at the California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. His research focuses on American institutions, race and ethnicity, and elections. His research has been published in Legislative Studies Quarterly, Social Science Quarterly, Politics, Groups and Identities, the Journal of Asian American Studies, and Politics and Religion.