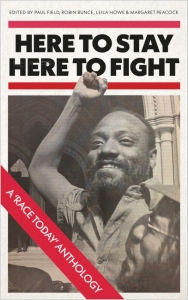

Here to Stay, Here to Fight, edited by Paul Field, Robin Bunce, Leila Hassan and Margaret Peacock, is a new anthology of the reports, essays and interviews published by the Race Today Collective, which ran from 1974-88. Tracing the arc of Race Today’s archive through this collection, Helen Mackreath observes that Here to Stay, Here to Fight is far from a historical document; instead, it is part of our urgent collective present.

Here to Stay, Here to Fight: A ‘Race Today’ Anthology. Paul Field, Robin Bunce, Leila Hassan and Margaret Peacock (eds). Pluto Press. 2019.

The shudders of the break-up of imperial formations occurred in conjuncture with the free-flowing visions offered by the anti-colonial imagination. By the 1970s the streets of Britain were a testament to all the messy contradictions emergent from that space. The boundaries of who could belong, and on what terms, were constantly being redrawn as the contours of epochal change were being struggled over. Citizens of all parts of the British Empire were arriving in the British metropolis. They were, in the words of Colombia University anthropologist David Scott in a book of the same title, ‘conscripts of modernity’: those who helped forge and consolidate the new postcolonial sovereignties through their cheap labour.

From the 1950s onwards, citizens from (increasingly former) colonial nations came in rising numbers from the Caribbean, from Azad Kashmir, from Dominica, from Kingston, Jamaica, from Port of Spain, Trinidad, and many countries in Africa including Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya and South Africa. As Farrukh Dhondy writes in Here to Stay, Here to Fight:

The immigrants went where the jobs were. The Mirpuris and Punjabi ex-peasantry from Pakistan were welcome first on the night shifts, and soon on most shifts of the Yorkshire and Lancashire textile mills […] The Bengalis of East Pakistan, later citizens of independent Bangladesh, mostly the rural dwellers of the eastern district of Sylhet, occupied the poorer streets of the East End of London (106).

These new members of society were caught in the trap of both desire and rejection by Liberal Britain, which wanted ‘to acknowledge their debt to the vast populations they had transferred as indentured labour from one continent to another’, but also ‘to deny those same populations, whom they had enlisted as British subjects, citizenship of the UK’ (105) (the implications of which are being felt very keenly today by the ‘Windrush Generation’). ‘These were decades of British pragmatism, liberal and racist as economic necessity seemed to demand’ (Dhondy, 105).

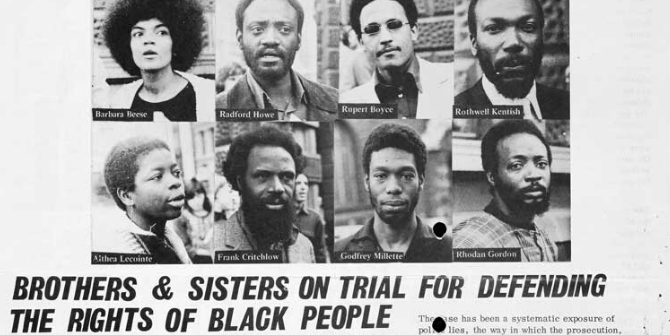

By the 1960s, Britain was experiencing the violent convulsions of that uneasy pragmatism. Ferocious riots in Notting Hill, London, in which hundreds of white youths, stoked by far right groups, chased and attacked the mainly Caribbean population, escalating to a week of confrontation at the end of August 1958, were the first direct signs of suppressed tensions bubbling to the surface. Organising among political groups that were extensions of radical nationalist and workers’ struggles in the Caribbean and new community structures forged the outlines of independent Black political, social and cultural organisations in Britain, led by figures in the anti-colonial movement in London in the 1930s and 1940s and influenced by Black Power movements in the US. In 1970 a group of Black radicals, part of a growing British Black Power movement, stood trial for 55 days at the Old Bailey on charges of incitement to riot after they protested sustained police provocation around the Caribbean Mangrove restaurant in Notting Hill. The acquittal of the ‘Mangrove Nine’, as they became known, forced the first judicial acknowledgement of ‘evidence of racial hatred’ in the Metropolitan police.

Image Credit: Battle for Freedom at the Old Bailey poster, circulated in the tenth week of the trial of the ‘Mangrove Nine’ (National Archives UK, catalogue number HO 325/143 No Known Copyright Restrictions)

Image Credit: Battle for Freedom at the Old Bailey poster, circulated in the tenth week of the trial of the ‘Mangrove Nine’ (National Archives UK, catalogue number HO 325/143 No Known Copyright Restrictions)

One of their number was Darcus Howe, a member of the British Black Panthers and charismatic activist, who successfully defended himself through an invocation of the Magna Carta. In November 1973, Howe was appointed editor of Race Today, originally the monthly publication of Chatham House’s Institute of Race Relations before breaking completely with the Institute less than a year later. Howe quickly steered Race Today towards a more radical outlet fighting for racial justice. Influenced by the Trinidadian historian C. L. R. James – whose groundbreaking The Black Jacobins was a classic account of the successful Caribbean slave rebellion, the Haitian Revolution beginning in the 1790s, and who was a key figure in the anti-colonial movement and countercultural resistance in London in the 1930s and 1940s – the journal attempted to clarify the experiences of racialised populations ideologically, giving race, gender and class struggles equal weighting at the core of its analysis. The Collective positioned themselves as anti-colonial and anti-imperialist Marxists, connecting struggles within and across ethnic groups in the Caribbean, and within and across English, Irish, Scottish and Welsh nationalities, ‘finding common ground in rebellions in Handsworth and Grenada, and strikes in Grunwick and Mumbai’, in the words of Adam Elliott-Cooper (251).

Writing the founding statement in Race Today in January 1974, Howe shifted the conversation around Britain’s Black population ‘From victim to protagonist’ in his call for greater agency:

The race question in Britain had been dominated by a liberal mystification of who and what black people are and consequently what they can and cannot do. The portrayal of the black population as ‘‘helpless victims’’ has been the central thesis of this tendency […] In opposition, a small but articulate body of black activists posed the revolutionary potential of Caribbean and Asian peoples (10).

Here to Stay, Here to Fight, an edited anthology of the reports and essays published by the Race Today Collective, which ran from 1974-88, has just been published. Its pages detail industrial strikes, reports of police brutality, accounts of grassroots campaigning, critical analysis, rally speeches and, perhaps most compellingly, the intimate details of the interior lives of women and men navigating the harsh realities of several cards – poverty, criminalisation, racist stigmatisation – stacked against them. The timespan of its publication includes the wave of urban riots that spread across Britain in 1981 as an immediate reaction to the deaths of thirteen young Black people in a fire in New Cross, Southeast London, but which were fuelled by more than a decade of bitter confrontations with the police and the repercussions of rapid urban deindustrialisation. The response to these riots signalled a shift in ethnic minority organisation towards the technocratic ‘diversity management’ which we are still living through today. As such, Race Today’s two-decade archive maps an arc from the discomforting ambiguities of the early postcolonial nation grappling with post-Fordism and with ever more militarised police repression towards a shift in the relationship between market and state under Margaret Thatcher, which had repercussions for how race was constructed, policed and instrumentalised.

***

Cynthia is 34 […] She often works three hours overtime to bring her salary up to £7.12 and she puts aside £1 for Ja. [Jamaica] each week but saves it for a few weeks as: ‘‘I can’t send £1 to Ja. looks too cheap.’’ She is still paying back the fare she borrowed to get to England in the first place. (85-86).

Middle-class and educated people migrating from the Caribbean islands frequently found themselves re-classified as ‘Black’ and working-class upon arrival in Britain and confronted with unions who were, for the most part, unable to grasp the issues facing the Black population or who were, unconsciously or consciously, racist themselves. From the dominions of the former British Raj, individuals were subject to sustained racist attacks and struggles over housing rights in London’s East End. One of the defining visions of Howe was his perspective that the category ‘Black’ was also inclusive of Asians. This allowed, as Elliott-Cooper writes, for previously disparate subjects of the British Empire, separated by land, sea, language and culture, to establish a relatively cohesive (although by no means uncontested) anti-racist struggle. Scholar David Roediger notes the importance and uniqueness of ‘British attempts to not only re-imagine race beyond Black and white but also to re-imagine Black as a category to unite and mobilise a variety of people’ (266), in one of the reflections on the legacies of Race Today. ‘Such understanding of race as a political colour, tied not just to skin and continents […] lasted only fragilely and too briefly in the British context where it came under ruthless attacks from Thatcherism’ (267).

This ‘racialised outsider’, as theorised by Satnam Virdee, helps to transform our understanding of the broad contours of British labour history. ‘It was minority men and women […] who were more able to see through the fog of blood, soil and belonging that forms such a constitutive component of racialising nationalisms,’ he writes. Here to Stay, Here to Fight provides a richly critical analysis of exactly those formations and the mechanics of their operation.

The myriad structures, borders and boundaries through which race permeates lives are found in housing, education, factories, in social welfare, personal welfare and the attribution of ‘second-class citizenship’. They were also, in this time period, acting in conjunction with the rapid deindustrialisation of urban zones. This was met by resistance in the form of squatters’ movements which helped Black families find housing (the Race Today Collective’s office was itself located in a squat in Brixton), Black supplementary schools and mass action against the violence of the police. Industrial action was held by the nurses’ strike, the strike at Imperial Typewriters, the Grunwick strikes, battles for better education and against police malpractice.

Image Credit: Grunwick strikers picketing 1977 © TUC Library Collections, part of Special Collections at London Metropolitan University

Image Credit: Grunwick strikers picketing 1977 © TUC Library Collections, part of Special Collections at London Metropolitan University

A great number of these movements were led by women. As Leila Hassan, the last editor of Race Today, notes, its members sought to change the socio-cultural structures that sustained oppression against minoritised groups, and women were at the vanguard of impelling such change. One of the most valuable, and under-examined, aspects of the anthology, as written by Kennetta Hammond Perry in her introduction to the chapter on ‘Sex, Race and Class’, is the ‘facets of an intergenerational conversation among Black women about strategies of resistance and modes of survival that were adapted over time to navigate life in Britain’ (70).

The Race Today Collective also emphasised giving a platform to, and tracing the development of, a distinctive Black and Asian British culture in the latter half of the twentieth century. Through cultural articles that describe the emerging artistic voices, visual artists and dynamic musical forms, contributors paid attention to the rich contours of life and the rhythms and harmonies which constitute moments of collisions between different cultures and spaces for political movement. In a 1982 lecture, James discusses American poet Ntozake Shange, whose words he describes as ‘containing the most drastic attacks upon present day society’ (192). (‘Sometimes you remind me of lady day / & I tell you sadness / The weariness in yr eyes / the walk you have / kinda brave when you swing yr hips / sometimes serenity in yr eyes / & the love always’). Toni Morrison told a Race Today interviewer in 1985 that she ‘resents the need for anger in art’ (96).

***

In the Introduction to the anthology, editors Hassan, Robin Bunce and Paul Field locate the significance of the timing of this new publication within the appetite among younger activists to learn about the recent history of Black radicalism in Britain, in ‘the struggle against police brutality and racism gaining new impetus through the Black Lives Matter movement and with the Far Right on the march again’ (1). These conditions are today giving rise to renewed political and social hopes which place racial justice at their centre. Reading this anthology from almost half a century ago in the current context of a political system which enables the Grenfell tragedy (and the current Leader of the House of Commons to condemn the victims as ‘lacking common sense’), the hostile migrant environment (in which The Home Office is using information gathered in ‘immigration surgeries’ at charities and places of worship to deport vulnerable homeless people) and the Windrush scandal, it may not seem like a historical document but rather part of our urgent collective present. The threads of racial justice which connect the anti-colonial resisters in the 1930s and 1940s, the activists involved with Race Today in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s and a new generation of activists behind numerous initiatives from decolonising educational institutes to various anti-racist campaigns remain taut.

But the particular constellations of structures these activists are struggling against continue to shift. Today the children of many of those documented by the Race Today Collective are part of a different suspect racialised community, defined no longer as ‘Young Asians’ but as ‘Muslims’ following the changing geopolitical situation in the aftermath of 9/11 and the invasion of Iraq in 2003. Racialised inequality is institutionalised in street stop and searches, unemployment and school exclusion, which, along with the rapacious market, privatisation of government functions and fatal police shooting of Mark Duggan, helped fuel London riots in the summer of 2011. Identity politics wrought by debates over Brexit illustrate the insistent ingrained blind-spots towards questions of Britain’s imperial legacy. Racism is becoming, according to Achille Mbembe, ‘both spectral and fractal’ as the technologies of racialisation become ever more insidious and ever more encompassing, creeping into modes of artificial intelligence and other future life worlds.

Race Today contributed to shaping a particular idea of humanity in which the negotiation of interests, sometimes discrete and competing, sometimes overlapping and convergent, did not privilege one over another. While the journal’s position may have been condemned at the time as too romantically revolutionary, it was not a monolithic account but a debate between readers, regular contributors and members of the Collective. Here to Stay, Here to Fight provides a useful dialogue with the past which throws light on different aspects of our present. The signs, movements and resistances which existed within those, now historic, conditions continue to be reproduced in new guises. The anthology ends with the poem ‘Bodycounts’ by Fred D’Aguiar, which pays tribute to the linkages between those threads: ‘for the sacred whose bones / pave Atlantic roads / for those beaten / choked / by fire / by police / breathe now / underground / underwater / over us all.’

- This review originally appeared at the LSE Review of Books.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/34gW7fj

About the reviewer

Helen Mackreath – LSE Sociology

Helen Mackreath is a first-year PhD candidate in Sociology at LSE. Her research interests include race, capitalism and postcolonial theory in relation to migrants in Istanbul.

Find this book:

Find this book: